Freedom of the press belongs to those who own one. (A. J. Liebling)

My husband likes to point out that while a typical small-circulation magazine may expose 500 readers to half a dozen stories every three months, about a hundred of my stories are downloaded every day. And every few days somebody reads them all (that’s nearly a novel, sizewise). So on the Net I have roughly the equivalent of a small lit-mag all my own, as opposed to the print journal that just held a manuscript for NINETEEN MONTHS and returned it with a form rejection slip. (Youngren, 1998, unpaginated)

Let me emphasize, however, that “virtual” should never be understood as meaning “almost” or “not quite” a community. As we first begin to think about or experience such communities, they may not seem as vibrant or vivid or muscular as some communities and identities more familiar or habitual to us, such as Canadian, Judaist, Muslim, Quebecois, or British Columbian. My argument, or hypothesis if you prefer, states that they have the potential to be just as fundamental to the identities of the some people as the existing ethnic communities whose existence we have taken for granted for decades or even centuries. (Elkins, 1997, 141)

Introduction

Prose fiction writers on the World Wide Web are a small tribe. I was only able to identify about 1,500 of them. Given that the best search engines only catalogue about a third of the sites on the Web, as many as 4,500 writers may have posted stories there. The fact that I combined a Yahoo! search with an additional search using lists of pages on fiction Web rings means I definitely found more writers than if I had just done the one search. However, there may be many sites which contain fiction but are not listed with search engines or Web rings. Moreover, many pages which are listed with search engines may contain fiction, but, because it is but a small aspect of their larger site, may not use fiction as one of its keywords, and, therefore, not be picked up by the type of searches I was conducting. In addition, many of the sites which I was unable to find may contain the work of more than writer. Let’s say that 4,500 is not a completely unreasonable estimate of the number of fiction writers posting their work on a web page. In 1999, there were an estimated 150 million people using the Internet. (Cerf, 1999, unpaginated)

A very small tribe, indeed.

To fully understand this tribe we must answer several questions. Who are the people who make up the tribe? This is not an obvious question, since, unlike traditional groupings of people, groupings of people on the Internet cannot be defined by simple geography. Most often, online people group themselves according to common activities or interests. It is necessary to go on to ask, then, what are the activities or behaviours which bind these people together? The intuition which spurred my initial interest in this subject was that the group consisted of people publishing their fiction writing on the World Wide Web. While this remains the thread which binds the people in this chapter together, we shall soon see that this one activity does not define an entirely homogenous group: what they do and how and why they do it are all variables with a variety of parameters.

Finally, in order to fully understand our subject, we must ask how do the people engaged in these activities view them? Or, more simply, why are these people engaged in this activity? Somebody who has written a short story has a number of established options for getting it to readers, including having it published in a magazine, an anthology of stories in a book and publishing it in print themselves. Why would writers choose one medium over the other? That is, what advantages does publishing online offer writers over traditional media (and what disadvantages does it have which must be overcome)? Moreover, digital publishing comes in many forms: stories can be emailed to subscribers, placed on discs or sent to newsgroups. What advantages does publishing on the Web offer writers over other forms of digital publication?

In order to explore this phenomenon, I conducted a survey of prose and hypertext writers and prose ezine editors using email. Since this is a relatively new tool, I shall begin this chapter with a discussion of my methodology. Using the responses to the survey, supplemented by statements the correspondents made in pages on their Web sites, I hope to answer these questions in this chapter.

Fiction writers on the World Wide Web may seem like a very specific subject. This dissertation is not about the Internet as a whole, for instance, but a single technology through which people access the Internet. Nor is it about what people using the Web do generally (although, hopefully, some general principles will emerge); rather, I chose a very specific activity as my subject. Despite this, it is necessary to begin by showing how I further delineated my subject.

This dissertation, for example, is exclusively about prose fiction writers. I chose not to consider writers of poetry because I knew some evaluation of the work would be necessary, and I didn’t feel competent to conduct even the most basic analysis of poems. In addition, this dissertation does not deal with fan fiction (referred to as “slash” fiction when the story revolves around the sexual adventures of characters who are not sexually involved, often two or more male characters), a genre of prose in which characters, settings and situations from popular media franchises (usually, but not always science fiction — the Star Trek franchise is a very popular basis of fan fiction) form the foundation of the stories. Fan fiction raises many interesting questions about how individuals position themselves within the larger culture; however, to do these questions justice would have required a lot of writing which would have taken me too far away from the issues I felt needed to be explored.

Finally, for purposes of this dissertation, I define a fiction writer as anybody who has written a piece of fiction. This may seem obvious, but in most other contexts it is not. Many people define writers by income, for example: if you make money from your writing, you can call yourself a writer, but if you don’t, you can’t. Other people define writers by genre: those who write literary fiction are writers, those who write science fiction, fantasy or romance are not really “serious” writers. These and other distinctions are artificial and, for my purposes, obscure the subject of interest, so I do not use them.

Comparison of Different Research Methods

Given the subject of prose writers on the World Wide Web, I was, as all researchers are, presented with the problem of how to collect information. Part of the fascination of the subject is that it is a relatively new area of research: the Internet is only 25 years old, and the graphical interface of the Web, at the time of my research, less than five. “The existence of the Internet and the World Wide Web (WWW) clearly provides new horizons for the researcher. A potentially vast population of all kinds of individuals and groups may be more easily reached than ever before, across geographical borders, and even continents. This is particularly true in relation to comparative social survey research.” (Coomber, 1997, unpaginated.) Since I was most interested in the practices of people who are actually putting their work online, it became apparent early on that I would have to use them as a primary source of information.

Having settled on this issue, the next question was how best to gather information from this group. As Rosenberg explains, “The most convenient way is of course to ask them. Failing that, we can experiment: We try to arrange their circumstances so that their behavior will reveal their beliefs and desires. But usually the only way to discern the beliefs and desires of others is to observe their behavior.” (1988, 32) Since the Web is an international communications network, I expected most of the people I would want to study to be scattered throughout North America, with some possibly in other parts of the world; this made observation more costly, in terms of both time and money, than I could afford. Experimentation, as Coomber suggests, should be considered a last resort, since laboratory conditions can never precisely duplicate the real world, a problem which can seriously bias results. The obvious method of collecting information would be some kind of survey of those doing the work online.

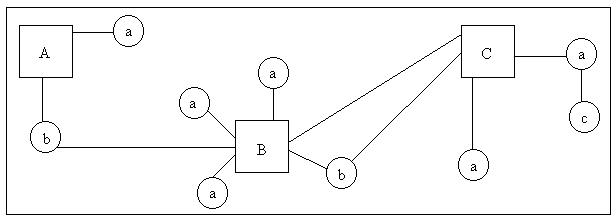

One of the advantages of digital communications networks is that they can not only be the subject of study, but the tool by which the subject is studied. As it happens, computers themselves have been used increasingly over the past 20 years in this type of social science research. “Electronic data collection is a growing area of application of computer technology.” (Helgeson and Ursic, 1989, 305) Computers have been both introduced into traditional interview settings, and have created possibilities for interviewing which did not previously exist (see Chart 2.1).

An example of the former is the use of portable computers in face to face interviewing. Here, either the interviewer types in the respondent’s answers as he or she gives them (Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing), the interviewer gives the portable computer to the respondent, who types in answers to questions him or herself (Computer Assisted Self-Interviewing with Interviewer Present), or some combination of the two. Another example of computers being used to aid traditional surveying methods is when interviewers type responses given to them over the telephone directly into a computer (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing).

An example of an interview format which was not possible before the advent of computers is Voice Recognition, where the computer calls a respondent, asks the first from a menu of prerecorded questions, listens for the respondent’s response and (presumably) understands enough of it to ask an appropriate follow-up question. A different example is the use of computer networks such as the Internet to distribute questionnaires online (Electronic Mail Surveys).

Although they differ widely, the various uses of computers in research have some characteristics in common. “Characteristic of all forms of computer assisted interviewing is that questions are read from the computer screen, and that responses are entered directly in the computer, either by an interviewer or by a respondent. An interactive program presents the questions in the proper order, which may be different for different (groups of) respondents.” (ibid) Which method a researcher uses will depend upon, among other things, the quality of the software (voice recognition software, for instance, still being in its infancy, isn’t very reliable) and the cost and availability of software and hardware. Intuitively, I decided to use the Internet to distribute questionnaires to writers who had placed their fiction on the Web.

| Specific method | Computer assisted form |

|---|---|

| Face-to-face interview | CAPI (Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing) |

| Telephone interview | CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing) |

| Self-administered form | CASI (Computer Assisted Self Interviewing) |

| CSAQ (Computerized Self-Administered Questionnaire) | |

| Interviewer present | CASI of CASIIP (computer assisted self-interviewing with interviewer present) |

| CASI-V (question text on screen: visual) | |

| CASI-A (text on screen and on audio) | |

| Mail survey | DBM (Disk by Mail) and EMS (Electronic Mail Survey) |

| Panel research | CAPAR (Computer Assisted Panel Research) |

| Teleinterview (Electronic diaries) | |

| Various (no interviewer) | TDE (Touchtone Data Entry) |

| VR (Voice Recognition) | |

| ASR (Automatic Speech Recognition) |

Chart 2.1

Taxonomy of Computer Assisted Interviewing methods

(de Leeuw and Nicholls II, 1996, unpaginated)

Email interviews have a lot in common with traditional mail interviews: they are received by the correspondent in text form, which requires that the respondent be literate; the respondent can do them in her or his own time, which allows for more complex and numerous questions; errors don’t creep in because interviewers can subconsciously “lead” respondents to specific answers (nor can the interviewer intentionally “cheat” by leading the respondent to answers conforming to the interviewer’s expectations). Email interviews compare favourably to in-person interviews, where the respondent has to answer in the time the interviewer is present (requiring simpler and less numerous questions), and because the in-person interviewer can consciously or subconsciously bias the respondent. They compare unfavourably to in-person interviews, which do not require respondents to be literate. (Since my survey was of writers, however, I assumed that literacy was not an issue.)

Mail and in-person surveys have certain advantages over email surveys. For one thing, they do not require special equipment (computers), which are both expensive and require that the respondents have the skills to use them. (Here again, though, if one is researching the behaviour of people online, as I am, one must assume that potential respondents have access to computers; otherwise, they would not be part of the phenomenon being researched in the first place.) Furthermore, in-person surveys have advantages over both forms of mail surveys: for one, the respondent of the former is not free to ask others for help answering questions, as he or she is in the latter. For another, non-verbal behaviours may be noted during in-person interviews, whereas they are impossible to note in either form of mail survey.

Email surveys do have some advantages over both of the other two forms, however. It is a relatively simple matter to customize survey questions for specific sub-groups within the research population; this is somewhat more difficult for regular mail surveys, and very difficult for in-person surveys. Where answers are numerical, it is a relatively simple matter to input the numbers into spreadsheet programs which can perform a variety of calculations on them; with the other two types of surveys, since the information is usually collected on print forms, it has to be input into computers before calculations can be made, which adds substantially to the amount of work the researchers have to do, as well as adding a potential source of human error.

The most important advantage that email surveys have over the other forms of survey is that they are far less time consuming and, therefore, far less costly. In-person surveys are very labour-intensive, which can make them highly expensive to undertake. Regular mail interviews require postage, of course, both from the researcher to the respondent and back again; depending upon the size of the population to be researched, this can very expensive. Email surveys avoid these costly steps. For this reason, under the right circumstances, they have the potential to “democratize” social science research, giving individuals or small groups the potential of doing large scale research. I am not exaggerating when I say that the time and cost of doing the research on which this dissertation is based would have been prohibitive for me, a single graduate student, using any other method.

Note that I claim that email research must be conducted in the right circumstances. As has already been pointed out, one needs a computer and the skills to use it to answer an email survey. In 1999, slightly less than a third of American adults, 92 million (INT’L.com, 1999b, unpaginated), and under half of Canadians, 13.5 million (INT’L.com, 1999a, unpaginated), used the Internet. Any survey of the general population of either of these countries by email, then, would be necessarily skewed because over half the population would not be eligible to respond. (By way of contrast, telephone surveys generally ignore the three per cent of the North American population which does not have phones, while mail surveys do not count the relatively small number of North Americans who do not have permanent home addresses.) Until computers have the same home penetration that telephones do, they will not be appropriate for general surveying. However, as a tool for learning about groups of people who are already online, email surveys appear to be the best tool.

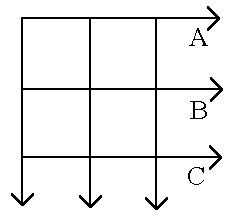

These and other similarities and differences between the three methods of research are shown in Chart 2.2.

How the Email Survey Was Conducted

For the present survey, the questions were written to be as general as possible in order to elicit the widest possible response. Some of the respondents objected to this. “If you don’t mind I won’t respond to your questions,” one writer stated. “In general I think you are asking the wrong questions. Simple questions usually get simple answers, and the subject you are aiming to clarify does not lend itself to simple questions.” (Beardsley, 1998b, unpaginated) As it happened, I had conducted a less ambitious version of the survey in 1996, and was satisfied that the answers to simple questions could reveal complex patterns. The reader of the current volume can, of course, judge the results of the survey for her or himself.

For this project, I identified five groups whose work contributed to the distribution of fiction on the World Wide Web: writers who put their work on their own Web pages; writers whose work appears in ezines; editors of ezines; writers of hypertext fiction, and; writers of collaborative fiction. I defined an ezine as a Web page with the writing of more than one author. I considered collaborative fiction to be a subset of hypertext where the segments are written by different people rather than a single author.

The questionnaire sent to writers with their own pages was basically the same questionnaire I used in 1996. The questionnaire sent to the other four groups used this questionnaire as the template, adding or removing questions to reflect what I thought would be the specific interests of each group. (The five questionnaires are reproduced in Appendix A.)

| in-person | ||

|---|---|---|

| interviewer present | interviewer absent | interviewer absent |

| oral | ||

| literacy not important | literacy necessary | literacy necessary |

| equipment unnecessary | equipment necessary | equipment unnecessary |

| no incompatibility problem | compatibility problem | no incompatibility problem |

| special skills unnecessary | special skills necessary | special skills unnecessary |

| population not an important issue | population an important issue | population less of an issue |

| synchronous | asynchronous | asynchronous |

| limited by time | unlimited by time | unlimited by time |

| completed at once | completed at leisure | completed at leisure |

| physically invasive | not physically invasive | not physically invasive |

| date of interview precise | date of interview less precise | date of interview imprecise |

| interviewee’s comfort no issue | interviewee’s comfort assured | interviewee’s comfort assured |

| questions must be simple | questions can be complex | questions can be complex |

| summarization difficult | summarization possible | summarization not possible |

| additional research unlikely | additional research possible | additional research possible |

| interviewer control | interviewee/programmer control | interviewee control |

| branching errors (interviewer) | few branching errors | branching errors (interviewee) |

| customized survey difficult | customized survey possible | customized survey difficult |

| random question order difficult | random question order possible | random question order difficult |

| calculations can be difficult | calculations are simple | calculations can be difficult |

| hard not to answer questions | easier not to answer questions | easy not to answer questions |

| non-verbal behaviour noted | non-verbal behaviour unnotable | non-verbal behaviour unnotable |

| probing possible | probing not possible | probing not possible |

| potential interviewer errors | no interviewer errors | no interviewer errors |

| intimate subject discomfort | discomfort lessened | discomfort lessened |

| social desirability bias | social desirability bias lessened | social desirability bias lessened |

| validation after interview | some validation during interview | validation after interview |

| interviewer cheating possible | interviewer cheating not possible | interviewer cheating not possible |

| interviewee cannot be helped | others can help interviewee | others can help interviewee |

| irrelevant info takes up time | irrelevant info more easily ignored | irrelevant info more easily ignored |

| addressing not an issue | bad addresses are usually known | bad addresses aren’t as easily known |

| interface not an issue | screen hard to read off of | paper easier to read |

| information limited to speech | information limited to screen | information limited to page |

| expensive | potentially least expensive | potentially less expensive |

Chart 2.2:

Comparison of Surveying Techniques

Finding the subjects was a relatively straightforward matter: I conducted searches using the Yahoo search engine, using the terms “online fiction,” “fiction ezines” and “hypertext fiction.” This yielded a large number of pages. Going through the pages of individual writers, I found that many belonged to web rings. A web ring is a list of pages connected by a common theme: “In each of its tens of thousands of rings, member web sites have banded together to form their sites into linked circles… Through navigation links found most often at the bottom of member pages, visitors can travel [to] all or any of the sites in a ring. They can move through a ring in either direction, going to the next or previous site, or listing the next five sites in the ring. They can jump to a random site in the ring, or survey all the sites that make up the ring.” (Starseed, Inc., 1998, unpaginated) By accessing Web ring lists of pages with fiction on them, I was able to gain a lot more names. From there, it was a matter of going to each page, identifying the author of each story or editor/publisher of each online magazine and collecting his or her name, email address and the URL of the story. In this manner, I harvested 1678 names in the five categories.

I began emailing the surveys on Saturday, June 27, 1998. One round of surveys was sent out per week; each round contained between 100 and 150 questionnaires. Thirteen rounds of surveys were sent in total. Respondents were given two weeks to reply, which meant that there was some overlap in responses coming in. To help me organize the responses, each email was sent with a number identifying which round it was a part of in the subject line.

Initially, the surveys were sent in batches of five to an email message, with a generic name in the subject line. Unfortunately, some people found this problematic. For one thing, the salutation “To Whom It May Concern” struck some as impersonal. “To Whom It May Concern? If you don’t take the time to find out who you are talking with, why should I take the time to fill out your questionnaire? Sorry for the tone–this miffed me a little.” (Hunter, 1998, unpaginated) Others recognized that this was the only way to open a letter going to more than one person: “I nearly took umbrage at your salutation until I read that you were sending this email to a number of people.” (Jennings, 1998, unpaginated)

Of greater importance is the fact that some people felt that this kind of survey was “UNSOLICITED and therefore annoying.” (Kay, 1998, unpaginated) Because of the ease with which email can be sent, many people find their inboxes flooded with messages from people they do not know on subjects in which they are not interested. This is often referred to as “spam,” after a sketch by the Monty Python’s Flying Circus comedy troupe in which the word spam is repeated ad neauseum. “I nearly deleted your message without reading it because I thought it was spam :-),” one person wrote. (Nixon, 1998, unpaginated) Aware that this was a problem, I had written in the covering letter to the questionnaire that it was an academic exercise, and that the information collected was not going to be used for commercial purposes. I thought that this would satisfy most people, whose objection was to unsolicited commercial email. What Nixon’s letter made me realize, though, was that some people would assume that my survey was spam from its generic subject line, and delete it from their inboxes before they ever got the chance to read my disclaimer. There is no way of knowing how many people didn’t respond to the survey for this reason, but it is possible that many didn’t.

This is in accord with the experience of Witmer, Colman and Katzman, who wrote: “Our results indicate that attaching an introductory paragraph with no forewarning to a full, on-line survey instrument is inadequate and inappropriate to the electronic environment.” (1999, 156/157) Had I been aware of it at the time, I would have applied their solution to this problem: sending a short email asking potential respondents if they would be willing to participate in a survey before sending them the survey itself.

As it happened, Nixon suggested a solution himself: “If I were you I’d try to personalize your message by including a reference to the author’s story in your subject line.” (1998, unpaginated) Starting with round six, I sent the questionnaire to each individual in a separate email and named the story that each had written in the subject line of the email. This hopefully reduced the number of people who interpreted the survey as spam, as well as minimizing the impersonality of this initial contact. Still, one person wrote: “I see that I am the only recipient on that particular distribution of your survey, and I am curious why you chose to query me, versus the other writers who appear in that edition of the on-line literary magazine. Or did you survey all the writers in that edition?” (Cochrane, 1998, unpaginated) Ultimately, no method is going to satisfy all research subjects.

In the covering letter of the survey, I told potential respondents that I would be willing to answer any question they had, so I responded to the above query. A couple refused to fill out my questionnaire because they didn’t believe me. “I would like to help you,” one explained, “however I have participated in several things of this nature in the past, where people said they would share the results of whatever project they were doing by sending me a writeup, or references, or something similar, and I have yet to see one person make good on this promise. I understand that things don’t always get finished or sometimes commitments get forgotten, but I’ve decided I’m tired of empty promises.” (Robert, 1998, unpaginated) In fact, I placed the name and email addresses of every one of the respondents to my survey who asked to be kept informed as to the progress of the dissertation into a file. When the first draft of the dissertation was written, they received a notice telling them about it, and giving a tentative date when it would be complete. I see no reason why I won’t be able to email them the URL of the dissertation if it is published online, or send them a copy of this chapter by email if it isn’t, as I promised anybody who asked.

To me, this is an issue of “fair treatment” of research subjects. If they devote the time to answer a survey, they have the right to know the results of the survey. The Internet makes this particularly easy, since email is neither as costly nor as time-consuming as mail; and, if the results are published online, notification of respondents can be as simple as an email containing a single line with a URL. As Robert’s quote suggests, being unresponsive to requests for information from subjects can result in their being less willing to participate in future research. If too many people on the Internet are burned by unethical researchers, the majority of people online may become hostile to research, to the detriment of everybody who may wish to conduct research on digital communications in the future, as has been noted: “research that violates an online group’s sense of privacy may leave ‘scorched earth’ behind for prospective future participants and future researchers as participants seek more private online spaces to carry out their group’s business or simply scatter under the scrutiny of researchers. [note omitted]”. (Marc A. Smith, 1999, 211)

The most frequently asked question by respondents was, “Please tell me how you got my name.” (Greenstein, 1998, unpaginated) At first, the answer seemed self-evident, given the public nature of the Internet. However, I realized that some writers have material in several electronic magazines and, therefore, would be curious about which venue I found which of their stories in, especially in the first five rounds of the survey, where the story was not named. I dutifully responded to each of these queries.

Another important lesson to me was that some survey subjects will not share my understanding of what they are doing. “What e-zine?” one writer asked “– are you talking about Duct Tape Press? That’s an e-zine?” (Muri, 1998, unpaginated) The line between an ezine and a personal page is fuzzy. Some writers put their stories on the Web page of a friend; they wouldn’t consider this an ezine, although, by my definition, it is. In retrospect, I should have defined my terms more clearly, which would have made the intent of my questions less open to misunderstanding.

Finally, it should be noted that the ease with which email can be sent works both ways: whereas somebody who didn’t like being sent a paper survey through regular mail would likely simply throw it away, email makes it trivially easy for respondents to online surveys to express their displeasure. This sort of vituperative email is known as a “flame.” In the course of the survey, I received two. One read in part:

For you to truly understand e-zines, web-zines, and the web as a form of media for communicating the many forms of art you should go and view this art. You should read what zinesters have to say in their articles.

I sincerely find it hard to believe that you are a PhD student.

If you decide to get serious about this and do your own research (instead of depending on zinesters to do [sic] just inform you) contact me again. If not, buzz off. (Kay, 1998, unpaginated)

The other was from science fiction writer Norman Spinrad. In answer to the question “Has your writing been published in traditional media?” Spinrad wrote: “Insulting!” When I asked where, he wrote “More insulting!” (1998, unpaginated) Spinrad seemed angry that I didn’t know who he was. In fact, I’ve known about his work since I was a teenage science fiction fan; however, I decided that all of my potential subjects would be asked the same set of questions.

Flames are the online equivalent of somebody shouting at you in person and slamming the door in your face. They don’t happen often, and the best response is to shrug and move on.

Of the 1678 surveys sent out, 300 were not deliverable. The most common reason for returned email, by far, was “User unknown.” Most likely, that is because the person switched her or his account to a new service provider or dropped off the Internet in the time between when I harvested their email address and sent out the questionnaire. Less frequently, surveys were returned with the message “Host unknown — Name server: man.network: host not found.” This usually means either that the Internet Service Provider’s computer is temporarily out of service because of hardware or software malfunction, that it has been bought by a larger ISP which subsequently changed all of its addresses or that it has simply gone out of business. Returned mail also sometimes came with the message “MAILBOX FULL” or “Mail quota exceeded,” both of which are self-explanatory.

The majority of returned email came from contributors to ezines; relatively little came from writers with their own Web pages. A moment’s reflection should show why this would be. Since a writer’s story resides on the ezine’s Web server, even if the writer drops off the Net the story will remain; not only can it be read when the writer is no longer online, but the return email address will continue to accompany the story even if the writer can no longer be reached there. When an individual moves to a different service provider or simply stops using the Internet, by way of contrast, his or her page will be immediately removed from the original server. Thus, which server a piece by a writer is on is revealed as an important aspect to keep in mind when conducting this kind of research.

In addition to the mail which could not be delivered, 12 people wrote to say that they refused to take part in the survey. When these numbers are subtracted from the number of surveys sent, that leaves 1366 potentially answerable surveys. Of these, 444 were returned filled out (32.5%). Despite all the rookie mistakes I made in the design and conduct of the survey, I am satisfied with this result. I suspect that this rate of return was based, in part, on the fact that subjects are more likely to respond to a survey if they have “a higher personal investment in the subject or a higher interest level in the general study.” (Witmer, Colman and Katzman, 1999, 156) The fact that the survey was on a subject of import to my respondents likely contributed to a higher response rate than I would have received if it had been on what type of soap they use or what car they drive.

Interpreting Online Survey Responses

Interpreting the information collected in an online survey is a challenge. To determine whether the sample of writers which I have collected is representative of people on the Internet as a whole, it is necessary to know how many there are. However, there is no way of knowing for certain how many people use the Internet. A computer may be used by a single person in his or her own home. Or the person may invite his or her friends over to use it. Or the person may live with his or her family, in which case several people may use it. In addition, businesses and schools often have pools of computers which may be accessed by dozens or hundreds of employees or students. Finally, public terminals are springing up in libraries and cybercafes (in addition to commercial terminals such as can be found at copy houses like Kinkos) on which anybody can anonymously access the Internet.

In order to determine the number of people with Internet access, researchers usually start with figures which can be more easily calculated: the number of hosts or domains on the Internet or the number of networks connected to it. A host is usually a single computer which connects many people at different terminals to the Internet. The name of a given host computer is usually the first thing after the @ sign in an email address; in my email address, inayma@po-box.mcgill.ca, for instance, the host computer is “po-box.” The domain name is usually made up of the rest of the address (ie: “mcgill.ca”), but is sometimes referred to as everything after the @ sign. There may be many host computers within a single domain (Mcgill, for instance, has Music, Musica, Musicb and CC in addition to Po-box). A network is a somewhat arbitrarily defined collection of computers; it is often synonymous with the domain, but it need not be. Estimates of how many people are connected to the Internet use either host, domain or network counts as their base, multiplying these known numbers by an estimate of how many people on average use each host, domain or network. These estimates can vary drastically (sometimes by as much as 100%) depending upon the assumptions used in the calculation. Just as there is no entirely trustworthy way of knowing how many people are on the Internet as a whole, there is no accurate way of knowing what percentage of these people are engaged in any specific activity.

Even if it is possible to get an accurate measure of how many people are connected to the Internet at a given moment, this figure will become quickly obsolete. Because computers are added or removed from the network on a daily basis, “We can trace out network connections throughout the world, even as we realize that the network’s constantly changing parameters ensure no printed map, not even an electronic one posted online, can be completely up to date.” (Gilster, 1993, 18) Individual users are coming on and dropping off the Internet all the time. Moreover, Web pages appear, move and disappear on a regular basis.

This last phenomenon had a direct bearing on my research. In order not to get too swamped by the work, I decided to read only the stories of the people who responded to my survey. For this reason, I waited until after the survey data had been collected before I began downloading the stories to read. Unfortunately, in the year and a half that passed between the time I sent out the questionnaires and the time I began writing the dissertation, many of the individual Web pages and some of the ezines could no longer be found at the addresses I had for them. If I had to do it again, I would store each story as I harvested the name and email address of the person who wrote it so that I would have it whenever I decided to read it.

There is a valuable lesson here, however. In order to rectify this problem, I did a Yahoo search for each ezine and individual Web page which could not be found on the URL where I had originally encountered it. I was able to find an additional 60 stories (21.0% of the 286 stories I read). This substantial number of stories had moved in the year and a half since I had first found them. In addition, there were other sites which had changed URLs which left notice of their address change at their original URLs. I didn’t catch all of these because some sites leave change of address notices on their home page, while I was trying to access interior pages with specific stories directly. In future, I will keep the URL of a site’s home page as well as any more specific pages I may want in order to be able to access a change of address page in case the specific page is not there. Perhaps most important, regardless of when I collect information online, I will revisit as many sites as I can as soon before publication as possible to ensure that the links to them still function.

Owing to this fundamental counting problem, I do not believe it is possible to do anything more than a cursory quantitative analysis of the survey results. In statistics, it isn’t always necessary to know the population of a group under study; there is a threshold number of responses past which a survey can be said to be representative of any population. However, although the total number of responses to the survey is above this threshold, none of the five individual survey segments is. Since the surveys are substantially different, I cannot say that any of them are representative. Therefore, when figures are used in the analysis which follows, they are meant to be suggestive rather than definitive.

In addition, the Internet is something of a moving target for any researcher. As has already been noted, pages are placed on and taken off the Web on a literally moment by moment basis. This means that any conclusions drawn about it at any given time are likely to be out of date soon after. In this dissertation, I have tried to tease out general principles which are likely to apply for a long time to come. (And, indeed, many of the concerns of writers in this survey echoed the concerns of those in the 1996 survey, suggesting that they are consistent over time.) However, it must be understood that this survey is a snapshot of the Web taken at a specific point in time.

More than twice as many of the writers who responded to my survey had contributed to electronic magazines (227) than had put fiction on their own Web pages (109). To better understand what they were doing, it is necessary for us to look at the ezines themselves before we look at what writers have said about their online experiences.

A Note About Terminology

Because the terms “zine” and “ezine” are close, it would be natural to assume that they are analogous phenomena. In fact, this is not the case. To avoid the confusion that may arise, it is necessary to take a brief look at the two terms.

In print, zine is a short form for the term “fanzine.” Such publications became popular in the 1960s when fans of science fiction films, television series and prose began putting out small magazines about their favourite works. Eventually, the word fan was dropped from the term when it became apparent that a wide variety of publications shared some common features with science fiction fanzines, not all of which were devoted to a single medium or cultural artifact.

Ezine is a short form for the term “electronic magazine.”

Owing to the large number of print zines (estimated at between 20,000 and 50,000 in 1995) (Ardito, 1999, unpaginated), it is hard to find a definition which will cover all examples. However, one which seems appropriate is that “zines are noncommercial, nonprofessional, small-circulation magazines which their creators produce, publish, and distribute by themselves.” (Duncombe, 1997, 6) Mark Gunderloy, founding editor of a zine review publication called Factsheet Five, and Cari Goldberg Janice claim that “Generally they’re created by one person, for love rather than money, and focus on a particular subject.” (1992, 2)

As we shall see, many ezines, by way of contrast, try to recreate the editorial process of print magazines, where there are a variety of editors and page designers who prepare the material for electronic publication. This is a far cry from the one-person operations of most print zines. Furthermore, again as we shall see, many ezines have tried to develop means of generating revenue for their work, and the publishers of others would like to be generating revenue; thus, they are not analogous to print zines, which are not commercially oriented.

The closest analogy to print zines online, I would argue, are personal home pages. They are the work of individuals. They are clearly not commercial. Although of widely varying degrees of quality, they do not profess to any form of professionalism. Duncombe’s claim that “In zines, everyday oddballs were speaking plainly about themselves and our society with an honest sincerity, a revealing intimacy, and a healthy ‘fuck you’ to sanctioned authority — for no money and no recognition, writing for an audience of like-minded misfits” (1997, 2) could just as easily be referring to these pages. There are some points at which this analogy breaks down; the point at which a personal page which solicits work from others stops becoming analogous to a print zine and becomes more like a print magazine is ambiguous. Nonetheless, I believe this distinction generally holds true.

For this reason, when I refer to zines in this dissertation, I am referring to print publications as defined by Gunderloy, Goldberg Janice and Duncombe. Unless otherwise stated, when I refer to ezines, I am referring to online publications which are close in spirit and structure, if not always in results, to print magazines.

The Variety of Subject Matter of Ezines

Print magazines exist on a continuum of specifocity based on the content they provide for what they perceive to be their audience. There are general purpose magazines (such as news magazines Time or Newsweek) with wide circulations. On the other hand, there are magazines with very specific subject matters (such as Radio Control Modeler or Stamping Arts & Crafts) which are targeted at much smaller, niche audiences. Such a continuum exists in the magazines which are devoted to fiction on the World Wide Web.

There are ezines which, with one typical limitation, are willing to accept anything: “We hate to be vague, but Utterants… does not have a preference in terms of style or content. The only thing we look for is quality.” ([Utterants@globalgraphics.com], undated, unpaginated). In these publications, links to literary stories can be found next to links to genre stories; there is no distinction between “high” and “low” literary forms, a distinction that leads many professionals to assume that genre writing, by definition, cannot be “quality” writing. By breaking down the distinction between high and low forms, these ezines try to reach the widest possible audiences, offering a little something for every taste.

Slightly down the continuum are the literary ezines. “The Richmond Review,” for example, “was established by novelist Steven Kelly in October 1995 as the UK’s first literary magazine to be published exclusively on the World Wide Web.” ([editor@review.demon.co.uk], undated, unpaginated) Like their print counterparts, literary ezines contain fiction which is about lived human experience. The subject matter can vary widely (although it rarely is allowed to drift into pure genre subjects), giving these publications a wide potential audience (keeping in mind that such an audience does not necessarily include fans of specific genres). Other examples of literary ezines include The Barcelona Review [http://www.web-show.com/barcelona/review/] and Eclectica [http://www.eclectica.org/].

Various genres are represented in the ezines available on the Web. Genre ezines are further down the continuum than literary ezines because, although sometimes quite popular, their potential audience is limited to fans of the specific genre. There are ezines devoted to the biggest genres: science fiction (Aphelion [http://www.aphelion-webzine.com/], for example, or Jackhammer E-zine [http://www.eggplant-productions.com/]) and fantasy (DargonZine [http://www.dargonzine.org/] and Faerytales [http://www.geocities.com/Area51/Shire/3951/door1.html]).

As the subject matter becomes more focused, the ezine moves further down the continuum. Thus, there are ezines such as HistOracle, which “focuses on historical fiction, blending historical fact with intriguing characters,” ([melanie@zoltan.org], undated, unpaginated) and Cafe Irreal, which specializes in “absurdist and surreal fiction.” (Whittenburg and Evans, 1998, unpaginated)

Not surprisingly, some of the fiction deals with subject matter of specific interest to computer users. “The Scarlet Netter,” for example, “began as an e-mail exchange between friends and lovers. Our frank discussions, log files, letters, and erotic fiction about On-Line Love Affairs and Internet Adultery began to take on a life of its own. It evolved into a slightly sophisticated, pointedly explicit, deeply personal and very modern Newsletter. With all the interest generated by the first few issues, it became apparent that a web site was called for (begged for, actually).” (Hester, undated, unpaginated) The defining feature of fiction in StoryBytes, to use another example, is that “Story length must fall on a power of 2. That means 2 words, 4 words, 8 words, 16 words, etc. That’s not simply an even number. To get a power of 2, you start with the number 2 and keep doubling (2*2=4, 4*2=8, 8*2=16, 16*2=32, etc.).” (Bubien, 1997, unpaginated)

Sometimes, the subject matter can be very specific: Dark Annie [http://members.aol.com/darkannie/], for example, features fiction on the subject of Jack the Ripper. In a similar vein, The Inflated Graveworm offers a very specific type of dark fantasy: “My question was, ‘Where in the world would H.P. Lovecraft, Lord Dunsansy–even Edgar Allen Poe–get published today?’ The answer was, unfortunately, ‘Nowhere.'” (David Powers, undated, unpaginated) According to its publisher, Idling “was started as an experiment to see what kind of material was being written on a particular subject: in this case, unemployment.” (Wakulich, 1998, unpaginated) Publications which have very specific content probably can muster only a small readership. As we shall see, the Web gives publishers of such niche magazines some important advantages over print.

Moving back up the continuum, it should also be noted that there are several ezines which, while not devoted to a specific type of content, put limitations on who can contribute. “The TimBookTu Homepage,” for example, is designed to be a showcase for up-and-coming African-American writers and poets who desire a place to have their works made available to the World Wide Web audience.” (Vaughan, Jr., 1997, unpaginated) To use another example: “Blithe House Quarterly considers unpublished short stories by emerging and established gay, lesbian and bisexual authors for publication.” (Alvarez, undated, unpaginated) There is no restriction on who can read these publications, of course, but they are more likely to be read by members of the minority group which are their intended writers. For this reason, they should be placed near genre publications on the continuum.

Various other niche audiences are served by fiction ezines. Some may be written by and for religious groups: “MorningStar is a quarterly electronic publication of the Writing Academy, a not-for-profit organization of Christian writers.” (Kyrlach, 1997, unpaginated) Others may be written by and for people who live in a specific area: “Welcome to the website of Border Beat, the Border Arts Journal, a quarterly publication presenting literary and visual arts from and about the U.S.- Mexico border region, Mexico, and the American Southwest.” (Carvalho, undated, unpaginated) There is at least one ezine, The Twilight Times, that positions itself as catering to a niche taste which is not accommodated by other magazines, in print or online: “I’ve been on the internet a few months and have met dozens of unpublished writers who have real talent. Twilight Times was created to present the works of those writers whose stories ‘blend’ genres, are too ‘literary’ for other zines or seem too mainstream or ‘quirky’ in tone.” (Quillen, 1998, unpaginated)

One other category worth noting is ezines which contain fiction in more than one language. “PARK & READ,” for example, “is the European Internet Literature Magazine which is open to every language spoken on this continent. While the first issue of PARK & READ was mainly in German we are happy to announce the second issue containing a lot of texts which were originally written in English or Spanish. Most texts were translated at least into one other language.” (Zinner, 1996, unpaginated) The Barcelona Review, perhaps not as ambitious, claims to be “the Web’s first electronic review of international contemporary cutting-edge fiction in English/Spanish bilingual format. (Original texts of other languages, such as Catalan, the official language of Catalunya, are presented along with English and Spanish translations as available.)” (Jill Adams, undated, unpaginated) I’m not certain where on the continuum to place multi-lingual publications. On the one hand, they have an increased potential readership: the combination of those who speak the various languages in which their stories are written. On the other hand, they may still encounter cultural barriers: are there a lot of readers interested in works that describe how other societies are structured, how other people live? If not, the potential increased readership may be ephemeral. This is a subject which calls for further investigation.

As the World Wide Web becomes a place known for the publication of fiction, the number and diversity of niche publications will grow. This can only benefit writers, who will have a greater opportunity to find a place where they can be published, no matter what the subject matter or style of their work, and readers, who will be able to find exactly the kind of writing they are looking for.

Age

As the World Wide Web is a new medium of communication, it is to be expected that most of the publications on it are also new. Nine (15.3%) of the 59 ezines I studied had only been in existence for six months or less; 14 (23.7%) had been existence for more than six months and less than a year; 21 (35.6%) had been in existence for more than a year and less than two years.

Interestingly, 15 (25.4%) of the ezine publishers claimed that their publication had existed for more than two years. Why interestingly? The graphical interface of the World Wide Web, the most important factor in making it accessible to a broad public, only really started catching on in 1995. Many of the publications which claimed a longer provenance would be older than this aspect of the Web itself.

There are a couple of reasonable explanations for this. As David Sutherland, editor of Recursive Angel explained, “We moved from print media to electronic due to ever rising costs of both paying contributors and printing issues.” (1998, unpaginated) Thus, a publication which had a print counterpart could claim the print publication’s history as part of its own for purposes of calculating its age.

Moreover, some publications had existed in other digital forms before they had migrated to the Web. DargonZine claims, with some credibility, to be the oldest continuous publication on the Internet: it had started publishing in 1985 (“About DargonZine,” 1998, unpaginated) on FSFnet (“DargonZine Writers’ FAQ,” 1998, unpaginated).

Thus, although the popular graphical interface of the Web is relatively new, one cannot assume that everything that appears on it is.

“Perpetual Proliferation”

Traditional print magazines, newspapers and newsletters are collectively known as “periodicals” because new issues appear at the end of a given period of time. Many of the ezines attempt to emulate print magazines by holding to a schedule. Of the 59 ezines represented in the survey: one (1.7%) published daily; one published twice a week (1.7%); two (3.4%) published weekly; one (1.7%) published every two weeks; six (10.2%) published monthly; one (1.7%) published eight times a year; five (8.5%) published once every two months; nine (15.3%) published quarterly; two (3.4%) published three times a year, and; two (3.4%) published twice a year.

While these figures suggest a great stability, in fact, they are not as solid as they may appear. Many publishers stated a frequency preference, then added that they may or may not make their avowed schedule. “I try to publish every two months,” one publisher admitted, “but sometimes fall behind and skip a month now and then.” (Carroll, 1998, unpaginated) This is the nature of small publishing: in print, small magazines and journals are notorious for missing deadlines and dropping issues completely.

Two of the publications (3.4%) were no longer publishing at the time of my survey. The stories remained on the Web for archival purposes. Four of the zines (6.8%) had started with one publishing schedule and, over time, changed to another. Twilight World, for instance, “used to be released every two months until early 1997. Then I started running out of stories and needed to wait longer until people would send them to me. It’s really irregular now.” (Karsmakers, 1998, unpaginated) Four of the publishers (6.8%) didn’t answer this question.

The remainder, 20 ezines (33.9) do not have regular schedules. Since stories do not have to bundled together (as they do in print), they need not be placed on a Web page at a specific time as a group. They can just as easily be place on the page individually as they are ready. This completely eliminates the need for a set publishing schedule, which makes some people rethink the nature of periodically publishing: “Currently it [The Pseudo-Magazine of Writings] is only a one-issue publication, in that if someone sends something to post, I post it when I have the time.” (G. Murphy, 1998, unpaginated) As the publisher of what used to be a monthly ezine put it: “I basically call the magazine a weekly, although I add updates on Monday, Tuesday, Wendsday, [sic] and Friday. So, it is bascially [sic] Perpetual Proliferation…” (Rick, 1998, unpaginated)

Regular schedules may be an artifact of print publishing which, in time, will be discarded by online magazines. However, some publishers argued that they had value even in the online world: “In order to give the issues ample time to be read, the publication still needs a regular schedule that the readership can count on. To constantly update the issues would not be fair to the writers or the readers (who would have time for a daily magazine; and how many people would read it daily?).” (Dave, 1998, unpaginated)

Readership

With print publications, defining readership is a relatively simple matter. We assume that when a publication claims that “X” numbers of people read it per month, that means that that number of people own discrete copies of the publication. Again, when a publisher claims that a book has been read by a given number of people, we assume that that many people have physical copies of it.

Defining the readership of online publications is not so simple. What does it mean when an online publisher claims that “We get about 150-200 hits/day.”? (Green Onions, 1998, unpaginated) Hits measure the number of times a remote computer asks a server to send it any element of a page. If a Web page is made up of plain text, then a person who accesses it counts as one hit (a request for the HTML). If, on the other hand, a page contains 20 graphics, the person who accesses it will count as 21 hits (20 for the graphics and one for the HTML). In this way, the most complexly designed pages tend to register the most “hits,” although it isn’t really a good measure of how many people actually access their page. The number of individual readers must be assumed to be somewhat less than the number of hits a site gets; how much less is impossible for somebody who doesn’t have access to the output of the publication’s tracking software to know. Some organizations use the term “unique readers” to refer to what, in print, would be simply readers, and to allow them to talk about readers in a more specific way than when publishers talk about hits.

Sometimes readership is more clear cut. One publisher wrote: “The actual ‘zine has done very well for the month and a half it has been in existence, now averaging about 4,000 hits to the home page a month.” (Farber, 1998, unpaginated) Measuring the hits to a single page, rather then every page on a site, gives a more accurate measure of readership, much closer to the idea of unique readers (although there is no guarantee that somebody who accesses a home page actually proceeds to read any of the contents of the ezine). When the editor of Jackhammer E-zine stated that “Our readership is somewhere around 600 right now,” (Henderson, 1998, unpaginated) I read it to mean that it had 600 unique readers, although she didn’t use that term. Still, most publications count their readership by the number of hits they receive. Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that the number of hits equals the number of readers, even though we know that this isn’t likely to be the case.

By this definition, readership of ezines which contain mostly fiction varies considerably. The publisher of The ShallowEND stated that it received “about 1000 hits per month” (Matteson, 1998, unpaginated) According to Heather Hoffman, editor, “Since its beginning three years ago, Interbang has doubled in print circulation, and gets about one hundred hits a day [3,000 per month] on the web site.” (1998, unpaginated) The publisher of now defunct ezine think said “We finished with a circulation of about 3,000 quarterly in print and about 25,000 hits per month on the Web.” (Sandvig, 1998, unpaginated) John Mahoney, creator of The Log Cabin Chronicles, claimed that “I now get about 100,000 hits a month from all over the world.” (1998, unpaginated)

How does this compare to other sites on the Web? According to an advertisement in the Globe and Mail, the combined readership of CANOE and its recent acquisition i|money is over 1 million unique readers and 30 million page-views a month. (“The ultimate synergy of tools and content,” 2000, B7) This suggests that the range of hits (1,000 to 100,000) for ezines with fiction is, in fact, not that large, relative to what is possible on the Internet. Perhaps more importantly, we see that the fiction ezine which claims the largest number of readers is still pretty small.

In terms of fiction publishing, however, the numbers are quite impressive. The Web unquestionably increased the readership of Shadow Feast Magazine according to its publisher: “It started off with only the work of friends to publish and only friends to read it. Now it has over 100 subscribers and approximately 3000 hits per issue.” (Kirkwood, 1998) (The term subscribers usually refers to people on a publication’s mailing list. Some publications mail plain text versions of the content of each issue to their subscribers who have trouble accessing the Web; others mail notices that the new issue is now available on the Web. Subscriber numbers are a good measure of how many people are interested in a publication.)

Another publisher argued that “We get about 150-200 [readers] a month when a new issue goes up. Not bad considering on paper I can only sell about 50 without going to a major magazine distributor to get it out there.” (Kline, 1998, unpaginated) The advantages of the Web over paper as a distribution medium for small press publications (and the work of self-publishing individuals) will develop as an important theme of this chapter.

Thus, although compared with commercial Web sites the number of hits fiction ezines get may not seem that numerous, relative to the number of readers they could get in print, ezine publishers feel they are further ahead. “I intend for it to get *really big*,” one publisher stated, “with a few thousand hits per day.” (Karsmakers, 1998, unpaginated)

Monetary Considerations

Financial considerations are an important aspect of any publication, on the Web no less than in Print. Most of the publishers who responded to my survey (41 — 69.5%) stated that they had no sources of revenue, and that they had no plans to get a source of revenue. The other 18 (31.0%) claimed that they either had one or more sources of revenue, or were hoping to have them in the future. Since few of them were actually able to generate revenue at the time of the survey, this overestimates the number who do; it would be fair to say that virtually all of the publications in my survey had no income.

Of the 18 publications which had or hoped to have revenue, almost all (15 — 83.3%) expected it to come from advertising. The publisher of one, Pif‘s Camille Renshaw, claimed that it was “already profitable” owing to its advertising revenues. (1998, unpaginated) Given the relatively low number of readers for most online publications, though, it is hard to see how they would be able to generate enough revenue from advertising to be financially self-sustaining.

Only three of the publications (16.7%) expected to make money from subscription sales. An equal number expected to make money from the advertising and subscriptions of a print counterpart to their Web publication; in a similar vein, two (11.1%) were planning on making money from selling print anthologies of the writing which had appeared on the Web. One publisher (5.6%) said he was going to sell t-shirts and other merchandise.

Another publisher was hoping for government support: “We have applied for funding from the Catalan and Spanish Ministry of Culture.” (Jill Adams, 1998, unpaginated) Given the newness of the Internet, Adams wasn’t optimistic about getting the funds, however. The example of the Canadian government’s funding of artwork on the Internet, from which a couple of general principles about government funding can be derived, will be explored in Chapter Four.

Finally, four of the publishers (22.2) said that they were seeking corporate partners; two of them named Amazon.com specifically. Online bookseller Amazon.com has a policy whereby any site which refers customers to it will be given a percentage of whatever sales Amazon.com makes to them. This strikes me as being akin to the symbiotic relationship between the bird and the hippopotamus whose teeth it cleans: a beneficial deal for both sides as long as the hippo doesn’t decide to close its mouth. We need more experience before we can tell if this is a sustainable source of revenue for ezines. (Percentages may add up to more than 100% because respondents could choose more than one answer.)

These and other financial issues will be taken up again at greater length in Chapter Three.

Not surprisingly, given the general lack of income of ezines, few can afford to pay their writers. Fully 49 of the 59 publishers (84.7%) did not pay their contributors. With the exception of two that paid a penny a word, each of the 10 (16.9%) ezines which paid contributors had a different rate: from 3 cents a word to $5, $15, $15-$25, $20-$40 or $5 to $50 per story (depending on length and, sometimes, how long the publication intended to archive the story). One publication offered writers 1/4 cent per word or $5, whichever was greater. This is not a lot of money.

The main reason for not paying writers was, of course, that the publications themselves have no revenue. “I don’t have the resources” to pay writers, one publisher, speaking for many, stated. (Vary Stark, 1998, unpaginated) Many of the publishers said that their aid in promoting authors was valuable: “I feel the free publicity I give is worth something to the writers,” was a common claim. This promotion not only comes in the form of publishing the work itself, but in linking the writer’s work in the ezine to his or her home page. As we shall see, many writers do value these things. Other publishers pointed out that publication itself was a form of payment since “We offer our megabytes which cost us…” (Bardelli, 1998, unpaginated) By publishing a writer’s work, an ezine saves the writer the cost of producing and maintaining her or his own Web page.

Some publishers tried to compensate for their lack of funding by offering other advantages to writers. “In lieu of pay,” the publisher of the bilingual Barcelona Review wrote, “we offer a translation of the writer’s work — worth quite a bit of money in itself (between 150 and 300 dollars).” (Jill Adams, 1998, unpaginated) Those who avail themselves of this form of payment are getting more value than those who are paid in cash by other ezines.

One publisher, though, was staunchly opposed to the practice of not financially compensating writers. “I consider non-paying publishers,” asserted Ana Maria Gallo, “principally those that have a paying subscriber base, to be reprehensible. The role of the publisher is to finance the project. If they can’t do that, *and* pay the contributors, I don’t feel they should be in the ‘game’.” (1998, unpaginated) Gallo seems to be objecting in particular to publishers who are making money from their venture but not sharing it with their writers. To my knowledge, none of the publishers of the ezines I studied were engaged in this practice.

How this lack of revenue affects the decision of writers to publish their work in ezines will be explored later in the chapter.

The “Accidental Publisher”

Few of the editor/publishers of fiction ezines had editing or publishing experience prior to putting out the magazines. Of the 59 publishers who responded to the survey, 18 (31.0%) claimed no previous experience whatsoever. Of those who had experience, 27 (45.8%) had had some of their own writing published, while 12 (20.3%) had been editors. Thirteen respondents (22.0%) had previously acted as print publishers, all of them for small presses: professional newsletters, print zines or small runs of their own writing. Only one of the ezine publishers claimed to have had experience with a major publisher, as a reader (1.7%). (Figures might add up to more than 100% because some people had experience in more than one of the categories.)

In this way, it would appear that most of the publishers of ezines are amateurs. This impression is reinforced by what I think of as the “accidental publisher” phenomenon.

Common sense would suggest that publishing an electronic magazine is an intentional act, that is, the publisher makes a conscious decision to solicit the writing of others and present it as a literary package. Many of them are not created by this process, however; they begin as a Web page with another purpose, and slowly evolve into literary ezines. This process can take many forms. Usually, the publisher starts with a home page for his or her own writings, which then grows to encompass the writing of others: “I started it [her ezine] to showcase my own stories. I now include work by others, and the webpage is about 10 times bigger than when I started it.” (Janine Smith, 1998, unpaginated) In one case, the original impetus was to showcase the work of another writer: “The main author (Craig) started writing these very funny stories on one of the iMusic bulletin boards out on the web. I loved them, and when I was ready to do my page I asked him if I could put his stories up. He said yes and since he’s a very prolific writer Story Land was born. Other people then started writing stories and I was able to get other peoples [sic] works out there” (Sandi, 1998, unpaginated)

In another case, the magazine began as a technical exercise: “TW3 began as a vehicle by which to demonstrate my then new company’s abilities in digital publishing. It worked, too, gaining us clients among nonprofits in the humanities and technology research. Over the last couple of years, however, it has grown into an entity in its own right and currently logs + or- 50,000 page views a month.” (Bancroft, 1998, unpaginated) There was also a case where technical considerations spurred a writer to create an ezine: “It started out as a section of my personal homepage to share my writing and some writing by my friends with the rest of the Internet. When I ran out of room in my account, I took the whole writing section and moved it to a free homepage. Setting it up as a zine was accidental. Free homepages require that you not just use them as loading space, so I essentially created an entire separate page for that writing section, and only later realized that it kinda fell under the category of e-zine.” (Darkshine, 1998, unpaginated)

Finally, one of the ezines was created out of the ashes of a failed print project. “I was approached to edit a print ‘zine,” the publisher explained, “but the backing fell through. I had already solicted [sic] some writing and art, so I decided to publish it on my own, on the web (as that required little backing).” (Farber, 1998, unpaginated)

The common thread to the genesis of these and other Web ezines is that the publishers backed into them; their original intention was not to become fiction publishers. The low cost of placing material on the Web (which, although disputed, will become a common theme in this chapter) is one obvious reason: adding a friend’s work to a print publications entails adding more pages, which drives up the cost. Once an online publication is established, adding pages does not add to the publisher’s cost (unless he or she hits his or her server limit, in which case the publisher will have to pay for more space). Perhaps a less obvious reason is the ease with which digital information can be edited. To change the content of a print zine from all one’s work to one’s work and that of others is not possible if copies have already been printed; even if caught before the print stage, it requires time and effort to redesign the physical layout of the publication, shoot new negatives for printing (or photocopy more pages), etc. Adding new material to a Web page, by way of contrast, may be a simple matter of uploading it to one’s server and adding a few lines of code to link existing material to it.

The accidental publisher phenomenon helps make sense of something that, at first blush, seemed odd.. In the section on methodology, I mentioned that a few publishers were surprised that I considered their activities “zine” publishing. I suggested that the reason was that I considered home pages with writing by more than their creator zines, even though their publishers might not define their activities in that way. The accidental publisher phenomenon suggests an additional reason: even those who publish what are undeniably zines may not takes themselves seriously as publishers. “My site isn’t an e-zine,” one publisher insisted, “merely a collection of music, writing, and artwork that people send me.” (Johnson, 1998, unpaginated)

Editing

In traditional publishing, material is usually edited before it is made available to the public. For the most part, this is true of ezines. Of the 59 editors who responded to the survey, 32 (54.2%) claimed that each story they published was edited once. In all but one of the cases, this edit was done by the publisher her or himself (in the other case, it was sometimes done by the editor’s assistant). This makes sense: because the majority of zines have no revenues and no plans to ever develop any revenues, they cannot afford staffs of editors.

Some of the ezines do have enough volunteers, or generate enough revenue, to be able to give stories more than one edit. At thirteen of the ezines (22%) each story is given two edits; three ezine editors (5.1%) claim to edit each story three times, and; one ezine editor (1.7%) claimed his publication edits four or more times.

It is worth noting that ten of the ezine publishers (17.0%) claim not to edit at all. “We rarely edit at this point…” one publisher stated. “I don’t do this for a living and no longer have time to correct sloppy work. If work is poorly written, we do not accept it.” (Bardelli, 1998, unpaginated) These publishers won’t accept just anything; stories submitted must meet their standards of originality and/or craft. However, they will not work with a writer of a marginal story to make it publishable. This makes submitting to these ezines an all or nothing proposition: “I take ’em like they is, or not at all. At this level, it’s not a matter of changing little things to make a work suitable for publication. Either you’ve got it, or you’re so far off there’s no point.” (Darkshine, 1998, unpaginated)

While most ezine publishers who didn’t edit stories cited practical reasons for not doing so, at least one offered an ideological reason: “The Inditer is not in the business of editing or censoring.” (Loeppky, 1998, unpaginated) Censorship? Editors? That’s not how we usually think of the editorial process, so we might want to ponder this point for a moment. The common belief is that editors help writers improve their texts by pointing out to them where their writing has not satisfactorily achieved what the writer had set out to achieve. To be sure, most writer/editor relationships are based on the idea that the editor’s goal is to help the writer fulfill her or his “vision.”

However, sometimes an editor has her or his own agenda which competes with this need to help the writer create his or her best work. Most often these days, this has financial roots: the editor does not see a market for certain subjects, treatments or writing styles, and gives the writer the choice of conforming to the publisher’s expectations or not being published. If there is a pattern of certain subjects, treatment or writing styles not getting published, some people believe that a form of “commercial censorship” has taken place. Others take the more extreme position that all editing is censorship since it necessarily interferes with the writer’s freedom of expression.

Some of the publisher/editors who did edit stories were also wary of editing the work of others. Richard Karsmakers, editor of Twilight World, stated that he only edited “typographically and gramatically. [sic] I don’t believe in editing someone’s work. I wouldn’t want others to edit my work either.” (Karsmakers, 1998, unpaginated) Since many of the publisher/editors of online magazines were originally writers or people with no publishing background who backed into their role as publishers, it makes sense that they would not have a traditional approach to editing.

Other Ezine Practices

A couple of other aspects of ezines should be mentioned.

All of the ezines that published editorial guidelines had a policy of claiming first publication rights to a story. In the vast majority of cases, these rights reverted back to the writer upon publication; in a small number of cases, they reverted back to the writer a short period (three to six months) after publication. What does this mean? From the moment a story was accepted to the point at which the rights reverted to the author, the author could not sell it to, or otherwise have it published by, another publication. This is fairly standard in print publishing, although it has implications for writers which will be explored later in the chapter.

As one might expect, most of the publications conducted the majority of their business by email, although a small number insisted upon regular mail submissions. Because there are a large number of word processing programmes, each ezine had to specify the format of the file attachments which they were capable of processing. To avoid this problem, some ezines only accepted plain text versions of submissions which had been pasted into the body of an email. However, other ezines would not accept submission pasted into email, the publishers arguing that important formatting information was lost.

Finally, most of the publishers limited the length of submissions they would consider from 1,000 to 5,000 words. However, a few of them allowed that they were prepared to make exceptions. “Articles and fiction can be up to 3000 words,” the submission guidelines of one publication read, “however, for good content, we will be flexible.” (“Submission Guidelines,” undated, unpaginated) A small number of ezine publishers either made room specifically for novels, or stated on their submissions guidelines page that they would consider serializing longer works.

Let us move our investigation of fiction publishing on the Web to a consideration of writers who publish their work on their own page and those who publish in the ezines of others. As we shall see, these writers have many common — as well as divergent — concerns.

Who Publishes on the Web?