NOTE: Many of the resources used for this thesis were found on electronic media, in particular the World Wide Web. References to such documents will contain much the same information as a normal footnote, including the author’s name, the name of the document and, where they are used, publication dates (which are often updated on Web pages), volume and issue numbers (in the case of online journals) and page numbers. In place of other publication data (particularly city and publisher), I have used each Web page’s URL (Universal Resource Locator), it’s “address” in cyberspace which makes it easy to find. A similar accommodation to the new medium is made in the bibliography.

Chapter One

1) Alexander Marshak, The Roots of Civilization (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972), 184. Marshak argues that many paintings, as well as carvings in rock and bone, did not depict the hunt, but were ancient methods of celebrating the fecundity of spring. Either way, they are early examples of narratives.

2) ibid, 373.

3) As an artist, I was appalled when I first read this: does this mean that my intentions when I create a work are irrelevant? As a student of media, on the other hand, I could see much wisdom in McLuhan’s observation. I have come, therefore, to the following accommodation: I believe that the medium affects its user regardless of the conscious intent of the person creating within the medium, but that, in addition, an artist does have the power to create a greater or lesser meaningful experience. I would rework McLuhan, therefore, to say, “The medium is a> message.”

4) Darryl Wimberley and Jon Samsel, Interactive Writer’s Handbook (Los Angeles: The Corronade Group, 1995), 107.

5) Ken Pimentel and Kevin Teixeira, Virtual Reality: Through the New Looking Glass (New York: Intel/Windcrest, 1993), 15/16.

6) Multimedia Demystified (New York: Random House/NewMedia, 1994), 95.

7) ibid.

8) ibid.

9) Stuart Moulthrop, “In the Zones: Hypertext and the Politics of Interpretation” (February, 1989, http://www.ubalt.edu/www/ygcla/sam/essays/zones.html), unpaginated.

10) Stuart Moulthrop, “Traveling in the Breakdown Lane” (http://www.ubalt.edu/www/ygcla/sam/essays/breakdown.html), unpaginated.

11) Philip Seyer, Understanding Hypertext: Concepts and Applications (Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Windcrest Books, 1991), 13.

12) ibid, 18.

13) ibid, 21.

14) Kathleen Burnett, “Toward a Theory of Hypertextual Design,” in Postmodern Culture (V3 N2, January, 1993, gopher://jefferson.village.virg.edu/0/pubs/pmc/issue.993/burnett.993), paragraph 2.

15) Theodore Nelson, Literary Machines, ed. 93.1. (Sausalito, California: Mindful Press, 1992), no page number.

16) Philip Barker, Exploring Hypermedia (London, England: Kogan Page, 1993), 12.

17) Julian Arnold, “Rec.arts.int-fiction Frequently-Asked Questions” ( December 4, 1995, ftp://ftp:gmd.de/if-archive/rec.arts.int-fiction/FAQ) unpaginated.

18) ibid.

Chapter Two

19) Margaret Mehring, The Screenplay: A Blend of Form and Content (Boston: Focal Press, 1990), 43.

20) Aristotle, Poetics, translated by Richard Janko (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett Publishing, 1987), 7.

21) ibid.

22) ibid, 10.

23) ibid, 13.

24) ibid, 20.

25) ibid, 48.

26) Ken Pimentel and Kevin Teixeira, Virtual Reality: Through the New Looking Glass (New York: Intel/Windcrest, 1993), 233.

27) Brenda Laurel, Computers as Theatre (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1992), 68.

28) ibid, 69.

29) There is some debate among Shakespeare scholars whether the playwright actually created his works with five acts in mind – some contend that he wrote without act breaks (many of which do not occur at logical places within his texts), but that his plays were divided into acts by the publisher of his first folios, a convention which has to this day has not been corrected.

30) Mehring, The Screenplay, 44.

31) Connor Freff Cochran, “Interactive Storytelling: A Critical Look at an Evolving Art, Part One” in InterActivity (V1 N5, November/December, 1995), 30.

32) Mehring, The Screenplay, 44.

33) See, for instance, Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, Syd Field (New York: Delacorte Press, 1982), page 44, or; Writing for Film and Television, Stewart Bronfeld (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981), page 56.

34) Mehring, The Screenplay, 54.

35) Field, Screenplay, 111.

36) ibid, page 137.

37) Mehring, The Screenplay, 128.

Chapter Three

38) Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think” (http://www.isg.sfu.ca/~duchier/misc/vbush), unpaginated. This article was originally published in The Atlantic Monthly, July, 1945.

39) ibid.

40) ibid.

41) ibid.

42) ibid.

43) ibid.

44) ibid.

45) Theodore Nelson, Literary Machines, ed. 93.1. (Sausalito, California: Mindful Press, 1992), 1/5.

46) ibid, 1/16.

47) ibid, 1/14.

48) ibid, 1/15.

49) ibid, 1/17.

50) ibid, 2/11.

51) ibid, 2/16 and 2/17.

52) ibid, 2/26.

53) ibid, 2/32.

54) ibid, 2/29.

55) ibid, 2/43 and 2/44. In fact, Nelson developed a complex scheme for determining copyright which includes different levels of access to documents, rules about making changes after a document has been “published” on the system and legal agreements which all users of the system would have to abide by in order to make such copyright work, a scheme to which I am only alluding here.

56) ibid, 2/45.

57) ibid, 2/53.

58) ibid, 2/33.

59) ibid, 3/6.

60) For a view of the development of Xanadu since Literary Machines was first published in paper in the mid-1980s, see, Gary Wolf, “The Curse of Xanadu,” in Wired (V3 N6, June 1995) and Andrew Pam, “Xanadu World Publishing Repository of Frequently Asked Questions,” V 1.44 (http://www.cris.ohio-state.edu/text/faq/usenet/xanadu-faq/faq.html, March 14, 1995).

61) Stuart Moulthrop, “Traveling in the Breakdown Lane” (http://www.ubalt.edu/www/ygcla/sam/essays/breakdown.html), unpaginated)

62) Charles Platt, “Interactive Entertainment: Who writes it? Who reads it? Who Needs it?” in Wired (V3 N9, September 1995), 146.

63) Frank Koelsch, The Infomedia Revolution (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1995), 87.

64) David Sheff, Game Over (New York: Random House, 1993), 1.

65) Koelsch, The Infomedia Revolution, 103.

66) ibid, 106.

67) ibid, 94.

68) Julian Arnold, “Rec.arts.int-fiction Frequently-Asked Questions” (December 4, 1995, ftp://ftp.gmd.de/if-archive/rec.arts.int-fiction/FAQ), unpaginated.

69) Koelsch, The Infomedia Revolution, 45.

70) ibid, 44.

Chapter Four

71) Charles Platt, “Interactive Entertainment: Who writes it? Who reads it? Who needs it?” in Wired (V3 N9, September, 1995), 149.

72) ibid.

73) ibid.

74) ibid.

75) ibid.

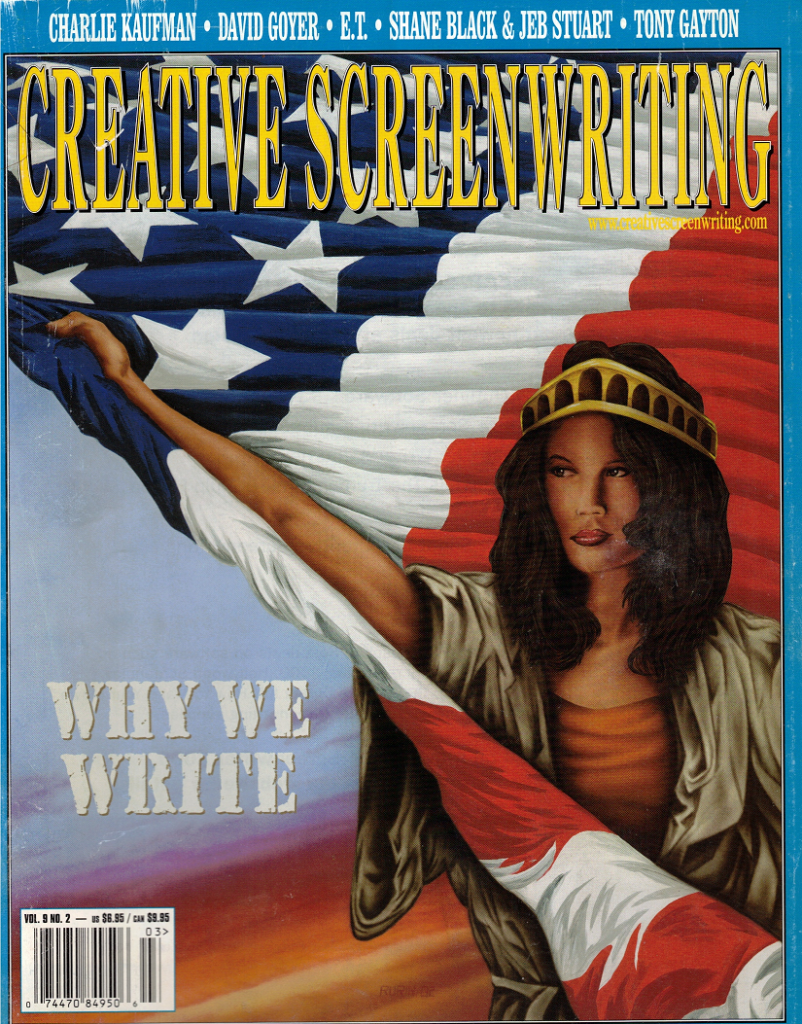

76) Brian Sawyer and John Vourlis, “Screenwriting Structures for New Media” in Creative Screenwriting (V2 N2, Summer, 1995), 95.

77) ibid, 98.

78) ibid.

79) ibid, 100.

80) ibid.

81) ibid, 101.

82) Darryl Wimberley and Jon Samsel, Interactive Writer’s Handbook (Los Angeles: The Corronade Group, 1995), 116.

83) ibid, 112.

84) Anne Hart, “A New Look: The Interactive Multimedia Market” in Creative Screenwriting (V1 N2, Summer, 1994), 59.

85) Wimberley and Samsel, Interactive Writer’s Handbook, 121.

86) ibid, 123.

87) ibid.

88) ibid, 132.

89) ibid, 141.

90) ibid, 142.

91) ibid.

92) ibid, 144.

93) ibid, 146.

94) A simple definition of irony would be when something claims to be one thing but is, in fact, another. However, irony can take many forms. The one which is ascendant in this culture is the irony which arises from the difference between something which is said and the manner in which it is said, which is supposed to indicate to the listener that the person talking does not believe what he or she is saying. This is a relatively easy form of irony known as “sarcasm.” A much more sophisticated form of irony comes from a character acting on information which proves, in the end, to be incorrect; when, for example, a character works towards a goal throughout a work of fiction, only to find, upon achieving it, that it wasn’t what he or she had expected. This second type of irony, a sort of structural or literary irony, is the sense of the term which I use here.

95) Sawyer and Vourlis, “Screenwriting Structures for New Media,” 95.

96) Platt, “Interactive Entertainment,” 195.

97) Gareth Rees, “Tree Fiction on the World Wide Web” (http://www.cl.com.ac.uk/users/gdr11/tree-fiction.html, September, 1994), unpaginated.

98) ibid.

99) ibid.

100) Platt, “Interactive Entertainment,” 195.

101) Marie-Laure Ryan, “Immersion Vs. Interactivity: Virtual Reality and Literary Theory,” in Postmodern Culture (V5 N1, September, 1994, gopher://jefferson.village.virg.edu/0/pubs/pmc/issue.994/

ryan.994), paragraph 34.

102)Wimberley and Samsel, Interactive Writer’s Handbook, 115.

103) Brenda Laurel, Computers as Theatre (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1993), 4.

104) ibid, 20/21.

105) This was true for most video and home computer games, where the participant had to solve a puzzle before the story could move forward. This is likely to be less true for more sophisticated narratives which will not contain puzzles, but allow the participant to choose from a menu of different dramatic scenes. By abandoning overt puzzles, creators of interactive narratives will lose the immediately involving effect they have on participants, but they will gain freedom from a largely artificial convention of early interactive media.

106) Platt, “Interactive Entertainment,” 197.

107) Wimberley and Samsel, Interactive Writer’s Handbook, 121.

108) Platt, “Interactive Entertainment,” 195.

109) Julian Arnold, “Rec.arts.int-fiction Frequently-Asked Questions,” (ftp://ftp.gmd.de/if-archive/rec.arts.int-fiction/FAQ, December 4, 1995), unpaginated.

Chapter Five

110) Ken Pimentel and Kevin Teixeira, Virtual Reality: Through the New Looking Glass (New York: Intel/Windcrest, 1993), 221.

111) Darryl Wimberley and Jon Samsel, Interactive Writer’s Handbook (Los Angeles: The Corronade Group, 1995), 114.

112) David Sheff, Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars and Enslaved Your Children (New York: Random House, 1993), 5. In fact, some believe that the entire video game market is twice as large as that for Hollywood films. However, while the market for films is fairly saturated, there is still a large amount of growth in the video game market, since many homes have yet to buy a game player or home computer.

113) Vsevolod Pudovkin, excerpt from Film Technique, in Gerald Mast and Marshall Cohen, eds., Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, third edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 85.

114) Sergei Eisenstein, Film Form, translated by Jay Leyda (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1949), 36. Although he remained adamant that his was the only true method of creating meaning in film, there is some evidence that a great deal of information, even contradictory information which invites the kind of interpretations Eisenstein theorized would be created through montage, can be created within a single shot. One need only look at the opening shots of such films as Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958) or Robert Altman’s The Player (1992), each of which is over six minutes long and introduces all the main characters and some of the conflicts which will be played out in the rest of each film, to see that a single shot need not be merely a conveyor of neutral visual information. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), which is meant to be seen as happening in one continuous shot (although he had to cheat a little in order to change film reels in his camera) is an extreme example of how much information can be contained within a single shot.

115) Eisensten, Film Form, 10. Eisenstein, a devoted Communist, was here applying Hegel’s dialectic to film: thesis (shot one) plus antithesis (shot two) leads to synthesis (the meaning created in the combination of shot one and shot two). This is clear on page 37, when he writes that meaning is created in film: “By collision. By the conflict of two pieces in opposition to each other. By conflict. By collision.” While some of his later theories seem ridiculous because they rely more heavily on Marxist theory than film reality, his early theories have become the basis of modern film and video production, as any fan of MTV can attest.

116) ibid, 30.

117) ibid, 32.

118) David A. Cook, A History of Narrative Film (New York: W. W. Norton, 1981), 139.

119) ibid.

120) ibid.

121) Pudovkin, excerpt from Film Technique in Mast and Cohen, Film Theory, 88/89.

122) ibid, 86.

123) Stewart Bronfeld, Writing for Film and Television (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981), 60.

124) Aristotle, Poetics, translated by Richard Janko (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett Publishing, 1987), 20.

125) Margaret Mehring, The Screenplay: A Blend of Form and Content, (Boston: Focal Press, 1990), 188.

126) Dwight V. Swain with Joye R. Swain, Film Screenwriting: A Practical Manual, second edition (Boston: Focal Press, 1988), 96.

127) Mehring, The Screenplay, 54.

128) Swain with Swain, Film Screenwriting, 95.

129) Anne Hart, “A New Look: The Interactive Multimedia Market in Creative Screenwriting (V1 N2, Summer, 1994), 59.

130) Charles Platt, “Interactive Entertainment: Who writes it? Who reads it? Who Needs it?” in Wired (V3 N9, September 1995), 148.

131) ibid, 147.

132) Rachelle Reese, “The Point of Interaction,” in Art Com (V10 I9 N43, November, 1990, ftp://ftp.gmd.de/if-archive/programming/general-discussion/ArtCom.43), unpaginated.

133) Platt, “Interactive Entertainment,” 148.

134) Ron Martinez, “Shape Shifter,” in Wired (V3 N4, April, 1995), 88.

135) Sherry Turkle, The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit (London: Granada Publishing, 1984).

136) Marie-Laure Ryan, “Immersion Vs. Interactivity: Virtual Reality and Literary Theory,” in Postmodern Culture (V5 N1, September, 1994, gopher://jefferson.village.virg.edu/0/pubs/pmc/issue.994/ryan.994), paragraph 16.

137) Reese, “The Point of Interaction,” unpaginated.

138) Bronfeld, Writing for Film and Television, 58.

139) Mehring, The Screenplay, 194. Although characters must be drawn as broadly as possible to allow for audience identification, they must also be grounded in the specifics of time and place, or else they may come across as caricatures of real human beings. This paradoxical principle is poorly understood. Consider the example of Oedipus: he is brave and has a thirst for justice for his people, qualities which are admirable enough that most of us would identify with them. But he also lives in ancient Rome and is bound by all the specific laws and customs of the time. Finding the universal in the highly specific is one of the most difficult aspects of creating believable characters which a writer will ever face.

140) Jim Gasperini, “If Brecht Were Alive Today, Would He Be Designing Computer Games?, Part Three,” in Art Com (V10 I10 N44, December, 1990, ftp://ftp.gmd.de/if-archive/programming/general-discussion/ArtCom.44), unpaginated.

141) ibid.

142) Reese, “The Point of Interaction,” unpaginated.

143) Daniel Crevier, AI: The Tumultuous History of the Search for Artificial Intelligence (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), 9.

144) David Graves, “Life-like Characters in Interactive Fiction,” in Art Com (V10 I10 N44, December, 1990, ftp://ftp.gmd.de/if-archive/programming/ general-discussion/ArtCom.44), unpaginated.

145) ibid.

146) Jerry Shine, “Herd Mentality,” in Wired (V4 I6, June, 1996), 100.

147) See Marvin Minsky, The Society of the Mind (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986).

148) For more on the theory and research behind this form of AI, see Bart Kosko, Fuzzy Thinking: The New Science of Fuzzy Logic (New York: Hyperion, 1993).

149) Graves, “Life-like Characters in Interactive Fiction,” unpaginated.

150) Joseph Bates, “Computational Drama in Oz,” in Art Com (V10 I10 N44, december, 1990, ftp://ftp.gmd.de/if-archive/programming/general-discussion/ArtCom.44), unpaginated.

151) ibid.

152) ibid.

153) Kevin Kelly, Out of Control (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1994), 325.

154) Bates, “Computational Drama in Oz,” unpaginated.

155) ibid.

156) Kelly, Out of Control, 325.

157) Bates, “Computational Drama in Oz,” unpaginated.

158) Bronfeld, Writing for Film and Television, 74.

159) Swain and. Swain, Film Screenwriting, 167.

160) While it may not matter for simple structures, building a model of speech for artificial characters makes more sense than having them choose from a number of prewritten responses the more complex you want to make a story. Prewritten responses have the drawback of limiting the number of choices a participant can make since the choices must be tailored to the available responses. Increasing the number of choices, on the other hand, increases the amount of memory needed for storage. Employing models of speech can be flexible and require a not onerous amount of memory.

161) Crevier, AI, 134/135.

162) ibid, 133.

163) Ryan, “Immersion Vs. Interactivity: Virtual Reality and Literary Theory,” paragraph 10.

164) Pimentel and Teixeira, Virtual Reality, 15.

165) Dominic Milano, “Case Study: The Journeyman Project 2: Buried In Time” in InterActivity (V1 N3, July/August, 1995), 75.

166) Dominic Milano, “Case Study: The Making of Myst,” in InterActivity (V1 N1, November/December, 1994), 42.

167) Mehring, The Screenplay, 41/42

168) I am indebted to Sara Diamond of the Banff School for the Arts for introducing me to this concept in a private conversation.

169) George P. Landow, Hypertext: The Convergence of Contemporary Theory and Technology (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 110.

170) ibid, 112.

171) In addition, any person who feels there is more to an interactive work can go back and, by making different choices, experience more of it. However, closure must be said to have failed to the extent that a participant feels the need to go back and re-experience a work because he or she feels the first experience was not, in itself, complete.

172) Stuart Moulthrop, “Traveling in the Breakdown Lane” (http://www.ubalt.edu/www/ygcla/sam/essays/breakdown.html), unpaginated.

173) Landow, Hypertext, 112.

174) Aristotle, Poetics, 113.

175) see Connor Freff Cochran, “Interactive Storytelling: A Critical Look at an Evolving Art, Part One” in InterActivity (V1 N5, November/December, 1995). Each of the 12 CD-ROMs which Cochran reviewed began with a non-interactive introductory sequence.

176) Landow, Hypertext, 109.

177) ibid, 110.

178) Michael Joyce, Afternoon, lexia 538, quoted in Landow, Hypertext, 113.

179) Omid Rahmat and Mark Giambruno, “The Online Platform,” in InterActivity (V2 N5, May, 1996), 44.

180) Kelly, Out of Control, 233.

181) In fact, even if it were possible to create an interactive work which offered a level of choice comparable to that of real life, it likely wouldn’t be esthetically gratifying. If, as I believe, we come to art because it offers an ordered refuge from the chaos of living, near infinite choice, by closely imitating reality, would undermine its whole reason for existing.

182) Ryan, “Immersion Vs. Interactivity: Virtual Reality and Literary Theory,” 45.

183) Milano, “Case Study: The Journeyman Project 2: Buried In Time,” 68.

184) ibid, 60.

185) ibid.

186) ibid.

187) ibid.

Chapter Six

188) Robert Gelman, “Time’s Running Out on the Multimedia Dream,” in InterActivity (V1 N3, July/August, 1995), 95.

189) Joy Mountford, “Essential Interface Design,” in InterActivity (V1 N2, May/June, 1995), 62.

190) John S. Atchley, “Cas, Chapter One,” (http:rampage.onramp.net/~jatchley/isfp_1.html, 1995), unpaginated.

191) As a child, I remember reading a mystery novel begun by Eleanor Roosevelt in which every chapter was written by a different well-known mystery writer.

192) Atchley, “Interactive Science Fiction Project” (http:rampage.onramp.net/~jatchley/scifin.html, 1995), unpaginated.

193) Atchley, “Interactive Science Fiction Project: Writer’s Guidelines” http:rampage.onramp.net/~jatchley/scifin.html, 1995), unpaginated.

194) Gareth Rees, “Tree fiction on the World Wide Web,” (http://www.cl.com.ac.uk/users/gdr11/tree-fiction.html, September, 1994) unpaginated.

195) ibid.

196) Atchley, “Writer’s Guidelines.”

197) Atchley, “Cas, Chapter One.”

198) Greg Rule, “Gingerbread Man: An Enhanced CD Title,” in InterActivity (V1 N3, July/August, 1995), 29.

199) ibid, 28.

200) ibid, 29.

201) ibid, 29/30.

202) Greg Rule, “Emergency Broadcast Network,” in InterActivity (V2 N2, February, 1996), 24.

203) ibid, 25.

204) ibid, 23.

205) Dominic Milano, “Inside Trilobyte,” in InterActivity (V2 N2, February, 1996), 48.

206) ibid.

207) ibid, 49.

208) ibid, 50.

209) ibid, 48.

210) ibid, 52.

211) Judy Malloy, “Electronic Storytelling in the 21st Century,” in Visions of the Future, Clifford A. Pickover, ed. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992), 137/138.

212) ibid, 140.

213) ibid.

214) ibid.

215) Sherry Turkle, The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit (London: Granada Publishing, 1984), 73.

216) Theodore Nelson, Literary Machines, ed. 93.1. (Sausalito, California: Mindful Press, 1992), 3/23.

217) Kevin Kelly, Out of Control (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1994), 252.

218) ibid, 252/253.

219) Sherry Turkle, “Who am we?” in Wired V4 N1 (January 1996), 151/152.

220) Kelly, Out of Control, 325/326.

221) Robert Rossney, “Metaworlds,” in Wired (V4 N6, June, 1996), 146.

222) Chip Morningstar and F. Randall Farmer, “The Lessons of Lucasfilm’s Habitat,” in Cyberspace: First Steps, edited by Michael Benedikt (Cambridge, Massachussetts: The MIT Press, 1992), 273.

223) ibid, 275.

224) Rossney, “Metaworlds,” 143.

225) Morningstar and Farmer, “The Lessons of Lucasfilm’s Habitat,” 286.

226) ibid, 287.

227) ibid, 285.

228) ibid, 288.

229) ibid.

230) ibid, 289.

231) Rossney, “Metaworlds,” 204.

232) ibid.

233) Ken Pimentel and Kevin Teixeira, Virtual Reality: Through the New Looking Glass (New York: Intel/Windcrest, 1993), 7.

234) Howard Rheingold, Virtual Reality (New York: Touchstone, 1991), 112.

235) Marie-Laure Ryan, “Immersion Vs. Interactivity: Virtual Reality and Literary Theory,” in Postmodern Culture (V5 N1, September, 1994, gopher://jefferson.village.virg.edu/0/pubs/pmc/issue.994/ryan.994), paragraph 8.

236) You will notice that these forms of virtual reality, which are the only forms which are likely to be pursued in the future, bear little resemblance to fictional portrayals of virtual reality. I do not believe connecting our brains directly to computers, as William Gibson projects, will be possible in the foreseeable future, not because we know too little about computers, but because we know so very little about the working of the human brain. While a version of Mandala system which completely surrounded the participant (perhaps using one-way mirrors so that cameras could track the participant without being visible to him or her) would come close to mimicking Star Trek‘s holodeck, it still would not allow for tactile feedback, which the television show’s version of virtual reality clearly does. The harness employed in Lawnmower Man seems like a logical outgrowth of the current goggles and gloves system; unfortunately, the filmmakers, not content with this reasonable projection into the near future, went on to claim that some unnamed drug could combine with virtual reality to increase the IQ of participants. Sigh.

237) Ira Nayman, “The Virtual Space,” in Cryptych (V1 N6, 1994), 45.

238) Randy Alberts, “Aladdin: A Work in Progress” in InterActivity (V1 N2, May/June, 1995), 26.

239) Ryan, “Immersion Vs. Interactivity,” paragraph 26.

240) Rheingold, Virtual Reality, 116.

Chapter Seven

241) see William Gibson, Neuromancer (New York: Ace Books, 1894) and its sequels, Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988).

242) Davis Albert Foulger, “Computers and Human Communication,” in Visions of the Future, Clifford A. Pickover, ed. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992), 63/64.

243) Roger Ebert, Siskel and Ebert, television performance, NBC, 8 January 1996.

244) Joshua Quittner, “Penn,” Wired, V2 N9, (September 1994) 150.

245) Dominic Milano, “Inside Trilobyte,” in InterActivity (V2 N2, February, 1996), 58.

246) Charles Platt, “Interactive Entertainment: Who writes it? Who reads it? Who Needs it?” in Wired (V3 N9, September 1995), 147.

247) ibid, 148.

248) Joy Mountford, “Essential Interface Design” in InterActivity (V1 N2, May/June, 1995), 62.

249) Joshua Quittner, “Penn,” Wired, V2 N9, (September 1994) 150.

250) Brian Sawyer and John Vourlis, “Screenwriting Structures for New Media” in Creative Screenwriting (Summer, 1995, V2 N2), 97.

251) Platt, “Interactive Entertainment,” in Wired (V1 N2), 196.

252) ibid, 195.

253) Michel Foucault, The Archeology of Knowledge, translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Harper Colophon, 1976), 23.

254) Sergei Eisenstein, Film Form, translated by Jay Leyda (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1949), 15.

255) Michel Foucault, The Archeology of Knowledge, translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Harper Colophon, 1976), 23.

256) Roland Barthes, S/Z, translated by Richard Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1974), 5/6.

257) Stuart Moulthrop, “In the Zones: Hypertext and the Politics of Interpretation” (February, 1989, http://www.ubalt.edu/www/ygcla/sam/essays/zones.html), unpaginated.

258) George P. Landow, Hypertext: The Convergence of Contemporary Theory and Technology (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 3.

259) Marie-Laure Ryan, “Immersion Vs. Interactivity: Virtual Reality and Literary Theory,” in Postmodern Culture (V5 N1, September, 1994, gopher://jefferson.village.virg.edu/0/pubs/pmc/issue.994/ryan.994), paragraphs 30/31.

260) ibid, 30.

261) Stuart Moulthrop, “Traveling in the Breakdown Lane” (http://www.ubalt.edu/www/ygcla/sam/essays/breakdown.html), unpaginated.

262) ibid.

263) Platt, “Interactive Entertainment,” 197.

264) Robert Gelman, “Time’s Running Out on the Multimedia Dream,” in InterActivity (V1 N3, July/August, 1995), 94.

265) Robert Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks, Understanding Fiction, 3rd edition (New York: Prentice Hall, 1979), 1.

266) Dominic Milano, “Inside Trilobyte,” in InterActivity (V2 N2, February, 1996), 49.

267) Gelman, “Time’s Running Out on the Multimedia Dream,” 95.

268) Platt, “Interactive Entertainment,” 197.