The beginning establishes your character within the framework of his predicament, nails down his objective, and carries the story forward to that point where Character commits himself to fight to the bitter end to attain his desire.

The middle reveals the various steps of Character’s struggle to defeat the danger which threatens him. And if you want your viewers to sit through it, you’d better cram it with fresh ideas, intriguing twists, and intensity of feeling.

The end sees Character win or lose his battle. Remember, in this regard, the story doesn’t truly end until the struggle between desire and danger is resolved, with some kind of clear-cut triumph of desire over danger, or vice versa.

– Dwight V. Swain with Joye R. Swain, Film Screenwriting: A Practical Manual

Impossible [incidents] that are probable should be preferred to possible ones that are unbelievable, and stories should not be constructed from improbable parts, but above all should contain nothing improbable…

– Aristotle, Poetics

The Importance of Structure

Consider a typical day. You wake up. You kiss your Significant Other on the cheek. You stumble into the bathroom and brush your teeth. You take a shower. You make yourself breakfast and eat it while reading the morning’s headlines. You drive to work. You spend eight uneventful hours on the job. You come home. Your SO isn’t back from his or her

job, so you make dinner for the two of you. Your SO enters just as the food is ready. Over dinner, you start to argue about where to go on your summer vacation; you want to go to France, your SO wants to go to Egypt. Later, you watch a couple of hours of television together and go to bed.

Most human activities which occur in a typical day would not make good drama. There is nothing inherently interesting in somebody brushing his or her teeth or watching two or three hours of television (although, in the proper context, they can carry a lot of dramatic weight). One of the most basic functions of a dramatist is to choose, from the vast catalogue of human experience, those experiences which will most involve an audience.

Out of our hypothetical day, one element stands out: the argument you have with your significant other. This could be the basis of an interesting scene, for, as every book on drama, no matter what the medium, emphasizes, the basis of drama is conflict. One character has a goal. A second character has a different goal, one which conflicts with the goal of the first character. The conflict between two or more characters working out their personal agendas is at the heart of most drama.

So, let’s look a little more closely at the argument. As you’re serving dinner, your SO seems tense, snappish, unlike his or her usual self. You ask what is wrong, but he or she doesn’t respond. You change the subject, trying to make small talk, but there is hostility in the air, so you fall silent. Most of the meal is, in fact, eaten in silence. Your SO churlishly offers to clean up, but by this time you’re getting annoyed at the situation, so you rudely refuse the help. Coming back into the dining room after washing up, you find your SO still sitting at the table, sipping a glass of wine. You ask if this might have something to do with the trip, at which point your SO finally starts talking bitterly about your refusal to go to Egypt. You complain just as bitterly about his or her indifference to your need to go to France. You go back and forth for several minutes, the argument becoming increasingly heated, until, exhausted, you agree to a truce. The two of you watch television in silence. Finally, just before you go to bed, your SO suggests that you find a compromise, to which you heartily agree.

Although this conflict could be very interesting, it would be difficult to make it so if you portrayed it as it actually happened. The several minutes you spend washing dishes, for instance, or the hours you and your SO spend in front of the television set, even with the argument simmering in the background, would quickly bore an audience. Here, again, it is the responsibility of the artist to choose, from all the possible ways of presenting a conflict, the one which will most involve the audience. This usually means eliminating those elements which do not directly contribute to the conflict and concentrating on its essential features.

Now, let us consider our argument one final time. You and your SO have chosen your vacation destinations because you both have family in the countries you wish to visit. You are very uncomfortable travelling to Egypt, however, because you are Jewish. This is a source of pain for your SO, who has an Arab background. When you first decided to make a life together, the two of you downplayed the differences in your backgrounds. Now, however, they are starting to become unavoidable, and you are both beginning to question the basis of your relationship. (Not all conflicts are created equal: the emotional stakes must be meaningful for the people involved. If this were just an argument about a vacation preference, it wouldn’t be very involving; because the background makes the conflict important for the two people involved, an audience is more likely to be emotionally drawn into it.)

Some of this may be stated directly in your argument, some of it may be in the subtext (the unspoken motivation behind a character’s actions). Some of this information may have been revealed in previous scenes (say, those which chronicled the beginning of the relationship), some may come up in later scenes, some may never be consciously acknowledged. These are all issues in managing the information contained in a dramatic work of art which fall to the artist; knowing which details will make the conflict most emotionally affective, how to display these details to the best effect, etc.

There is no magic formula for successful drama. Different subjects will require different approaches. Different artists will take different approaches to the same subject. And, while we each have our own ideas of what constitutes a successful work of art, the wide variety of approaches different artists take may be equally valid if the artists achieve the goals they set out to accomplish.

Does anything go, then? Not quite. There are guidelines, some dating back thousands of years, to help us structure works of art, to help us choose and order the most compelling events from the myriad of possibilities. This chapter will look at some of the traditional ideas of dramatic structure.

Aristotle

When discussing traditional ideas of narrative, a good place to start is Aristotle’s Poetics. Although written approximately 2,500 years ago, Poetics contains a lot of ideas which are relevant to artists today. As screenwriting teacher Margaret Mehring observes: “Aristotle’s Poetics is the basis for understanding all structures of storytelling. Then, if you wish, it can become a structure to consciously deviate from as you create your own ‘principles.’ Like painters learn basic methods of drawing and pianists learn scales and chords, writers learn classical – Aristotelian – dramatic structure.” [19]

Aristotle, a philosopher who revolutionized thought in a wide variety of disciplines, observed the major features of the plays which had been written up to his time, using their common features as a blueprint for what constituted a successful tragedy. It is believed that a companion volume to the Poetics took the same approach to comedy, but all but fragments of such a volume have been lost in time.

One of the features Aristotle noted revolved around how much time elapsed in a successful tragedy: “…with respect to length, tragedy attempts as far as possible to keep within one revolution of the sun or [only] to exceed this a little…” [20] Although the action of a play should take place within a 24 hour period, this does not limit the writer of a tragedy to events which take place in that period. In Sophocle’s Oedipus Rex, for example, the king’s pursuit of the truth (the action of the play) takes place in the space of a few hours; however, in the dialogue between characters, we are told of events which happened in the past, particularly the circumstances of Oedipus’ birth and childhood.

“Tragedy,” Aristotle continued, “is a representation of a serious, complete action which has magnitude…” [21] That is, the story must have important consequences, both for the main character and the society of which he or she is a part. Returning to the example of Oedipus, the play opens with the land ravaged by plague, bad weather and signs that something in nature is out of whack. As the king, Oedipus must find out what is wrong so that he may right the balance (he is unaware that he is the cause of the problem). In this way, the action of the story has serious consequences for both Oedipus and his society.

The completeness of the action was of particular concern to Aristotle, who described how it should manifest itself: “A whole is that which has a beginning, a middle and a conclusion. A beginning is that which itself does not of necessity follow something else, but after which there naturally is, or comes into being, something else. A conclusion, conversely, is that which itself naturally follows something else, either of necessity or for the most part, but has nothing else after it. A middle is that which itself naturally follows something else and has something else after it. Well-constructed plots, then, should neither begin from a random point nor conclude at a random point, but should use the elements we have mentioned [i.e. beginning, middle and conclusion].” [22]

Aristotle also believed that a proper tragedy took place in a single setting; all of Oedipus, for example, takes place within the courtyard of the king’s residence. Together, these ideas have come to be known as the three unities of Aristotle: unity of time, unity of action and unity of place.

Media which have come into existence since the time of Aristotle have weakened the importance of two of his three unities. Film, with its ability to juxtapose scenes which take place in vastly different times and/or places, seems to work against the unities of time and place. In fact, one of the most exciting techniques of film, intercutting between scenes in different places, creates tension in a way which is completely opposed to the unity of place. However, whenever a writing teacher admonishes his or her students to include in their work only that which is important to the story which they are telling, he or she is reinforcing Aristotle’s unity of action, an idea which continues to have broad applications to all narrative media.

Because of his emphasis on a succession of events arising logically from those which came before, Aristotle took a dim view of narratives which did not have a causal succession of scenes. “Among simple plots and actions,” he wrote, “episodic [tragedies] are the worst. By ‘episodic’ I mean a plot in which there is neither probability nor necessity that the episodes follow one another.” [23] Thus, every scene must have a specific place and purpose within the larger work.

Following this logic, Aristotle went on to argue that it was “obvious that the solutions of plots too should come about as a result of the plot itself, and not from a contrivance…” [24] The particular contrivance Aristotle was likely referring to has come to be known as the deus ex machina, or “god from the machine.” In some of the comedies of his time, the resolution to the story involved having god come out of the sky and sort out all the complications which had developed. This was effected by the use of an elaborate mechanism which literally flew the character playing the god onto the stage (hence the term). This did not satisfy Aristotle (and, indeed, most of us find something unacceptable about it) because, by arbitrarily resolving the conflicts between characters, their efforts and emotional traumas are diminished.

Finally, Aristotle explored the question of the emotional payoff of tragedy to its audiences, giving us the much-debated term “catharsis.” In one of the existing fragments of what is believed to be the second book of Poetics, Aristotle explained: “[If it is properly constructed,] tragedy reduces the soul’s emotions of [pity and] terror by means of compassion and dread, [which are aroused by the representation of pitiable and terrible events. By ‘reduces’ I mean that] tragedy aims to [make the spectator] have a due proportion [i.e. the mean] of [emotions of] terror [and the like by arousing these emotions through representation. Tragedy, like epic, has as its end the catharsis of these emotions, which gives rise to the pleasure proper to tragedy.]” [25]

Feelings of pity and terror being pleasurable? At first, this may seem like a contradiction, but as Pimentel and Teixeira explain, Aristotle “didn’t mean that the emotions were necessarily pleasurable, but that the release of the emotions was pleasurable (the popularity of slasher, horror, and thriller movies attests to the variety of pleasure people find in the release of unpleasant emotions).” [26]

Aristotle’s description of the purgation of emotion through catharsis was controversial in its time, although not for the reason it is today. Philosophers argued that, since the highest calling people could aspire to was intellectual contemplation about the nature of reality, theatre, by fueling people’s emotions, was a less exalted experience. Aristotle disagreed, claiming that by purging their emotions in the theatre, people could return to their homes and better contemplate reality.

In Aristotle’s view, art was a highly moral undertaking.

The Flying Wedge

It’s a writer’s greatest opportunity and worst fear – the blank page. Sitting down to begin a new project, the writer faces total freedom; literally anything can be done with a blank page. Some writers find such freedom exhilarating. Others face it with dread: how, out of the endless possibilities presented by the blank page, can I find something meaningful, something entertaining, something esthetically pleasing?

Introducing setting and characters greatly simplifies the task because every concrete choice a writer makes rules out a million possibilities. If, for instance, you have decided to set your work in Paris during the student riots of the 1960s, it cannot be set in Russia during the revolution, in modern-day Toronto or, in fact, any of the other myriad possible times and places (including wholly imaginary times and places) that are possible to choose from. In a similar vein, making your main character a 32 year-old black middle class woman living a conservative life forestalls the possibility that the main character can be anybody else the writer can imagine.

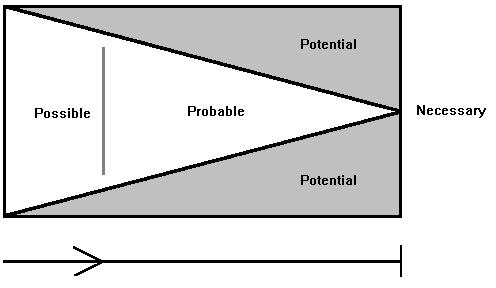

This same mechanism applies to the way a story unfolds: as incidents occur, they rule out the possibility of other incidents. As artist and academic Brenda Laurel explains: “Dramatic potential refers to the set of actions that might occur in the course of a play, as seen from the perspective of any given point in time (that is, a location along the axis of time, as the action of the play unfolds). At the beginning of the play, that set is very large — in fact, virtually anything can happen. From the instant that the first ray of light falls on the set, even perhaps before an actor has entered the scene or spoken a word, the set of potential actions begins to narrow. What could happen begins to be constrained by what actually does happen…” [27]

We begin a work with a man and a woman sitting at a table. If the table is in a kitchen, certain possibilities for action exist. If the table is in a restaurant, some of these possibilities are eliminated (for instance, a loud verbal argument is more likely in the kitchen than in the restaurant), others are created (for instance, a waitress is more likely to appear at the table in a restaurant than in somebody’s kitchen). Let’s make a creative decision: the man and woman are sitting in their kitchen. They begin to talk in quiet tones which suggest repressed tension; this makes it more likely that the scene will progress to an argument than passionate declarations of love (although it doesn’t rule out that possibility entirely). If the voices begin to rise, the argument becomes more likely. If the scene turns out to be an argument, then the work is more likely to be about a relationship which is falling apart than one which is happily chugging along. Additional scenes of tension reinforce this possibility, making other, happier storylines less possible. This movement from possibility to probability works at the level of both an individual confrontation and over the arc of an entire work.

“In Aristotelian terms, the potential of a play, as it progresses over time, is formulated by the playwright into a set of possibilities,” Laurel writes. “The number of new possibilities introduced falls off radically as the play progresses. Every moment of the enactment affects those possibilities, eliminating some and making some more probable than others… At the final moment of a play…all of the competing lines of probability are eliminated except one, and that is the final outcome… Thus, over time, dramatic potential is formulated into possibility, probability and necessity.” [28]

This concept can be neatly encapsulated by imagining what Laurel has termed the “Flying Wedge” (see Figure 2.1). The rectangle is the universe of possible choices an artist could make in creating a work. Read from left to right, the diagram shows how, as creative choices are made as the story progresses, the possible directions in which the story can go lessens. By the end of the work, the choices the writer has made should lead to a single, inevitable conclusion. (Remember that endings which do not arise from the necessity of the previous action of the work are not as esthetically satisfying, as when Hollywood tacks a happy ending onto an essentially dark, dramatic film, a modern form of what Aristotle referred to as the deus ex machina.)

Figure 2.1

The “Flying Wedge” indicates a plot is “a progression from the possible to the probable to the necessary.” (Laurel, Computers as Theatre, 70)

The flying wedge refers to a single, predetermined storyline, as we have experienced most traditional film and theatre. However, as we shall see, this analysis can be profitably applied to the multiple storylines made possible by interactivity.

Three Act Structure

Dramatic narrative, as found in modern theatre and film, has developed a three act structure. This was not inevitable. Shakespeare’s plays, for the most part, contain five acts. [29] Many modern playwrights use only two acts, as do most half hour television shows. However, especially in mainstream film, the three act structure is the dominant storytelling paradigm.

Simply put, the first act contains the introduction to the main characters and sets up the conflict(s) in which they will participate; the second act contains complications which make the task set for the main character more difficult while at the same time raising the stakes, making it more imperative that he or she succeed, and; the third act contains the resolution to the conflicts which have arisen in the course of the work.

“Most beginnings have the same ingredients -” Mehring writes, “the principal characters are confronted with a new experience and a problem to solve, a problem that doesn’t have an easy solution… The beginning starts the ball rolling. We meet the main characters, find out where the story’s going to take place, learn about the situation, receive information about the characters’ backstories, discover the characters’ goals and sense the source of the energy that will push the problem to its solution.” [30]

Mehring’s description of beginnings used to describe the first act of a play or film. However, Hollywood practice has evolved over the last 20 years to the point where this is now done in the first five or 10 minutes of a film. This has happened because of the perception that the beginning’s “most important job is to hook our interest; we have to want to continue, or it has failed.” [31] If you’ve ever felt that movies are somehow “faster” than they used to be, it is because there is less time spent on setting up characters and situation; in order to get the audience involved in a work within the first few minutes, filmmakers often start in the middle of the action, developing plot and character on the fly. In this way, you could say that the first act has become greatly foreshortened, or that some aspects of the second act have leaked into the first.

“The middle picks it up and gathers speed as the main character struggles to achieve his or her goal,” writes Mehring. “But it’s never easy for the main character – the protagonist – to achieve the desired goal. The struggle is long and arduous.” [32] The second act is traditionally longer than the other two to allow for the greatest development of the conflicts in the work. This is because, as I have already stressed, the essence of drama is conflict. [33]

“Endings, sometimes referred to as the denouement, contain the resolution to the problem first established in the beginning.” [34] While this is generally true, in terms of the three act structure, the ending begins at the point where the conclusion becomes

inevitable. Consider Alfred Hitchcock’s film Vertigo (1958). The ending would seem to be the final sequence, where Jimmy Stewart chases Kim Novak up a belltower, ending with him standing Christ-like in the belltower knowing that he has just caused the death of the woman he has loved (for the second time!). It would seem that the entire second half of the film is second act conflict leading to this relatively quick ending. In fact, the third act begins with the revelation that Novak is the woman Stewart believed he saw fall off the belltower earlier in the film. This revelation, which feeds Stewart’s obsession with making her over into the image of the woman whose death he believes he is responsible for, changes the direction of film, leading to the final resolution.

At the end of each of the first two acts are usually surprises which propel the action of the work forward, often in a new and unexpected direction (such as the revelation in Vertigo). Screenwriting teacher Syd Field refers to such surprises as “plot points,” defining them as “an incident, or event, that ‘hooks’ into the action and spins it into another direction. It moves the story forward.” [35] Plot points are easy ways of identifying the point at which one act is supplanted by another.

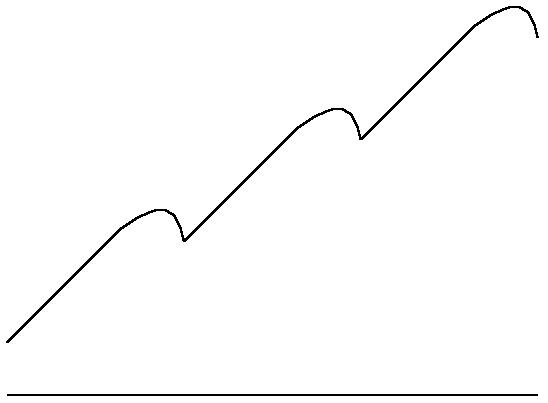

A simple visual representation of the three act structure can be found in Figure 2.2. Movement from left to right indicates forward motion in time. The rising of the diagram is meant to indicate the tension the audience will feel at the increasing level of conflict. At the end of each act, there is a slight hook downward indicating a lull in the forward motion of the story; these breaks usually come after a plot point to give the audience time to catch its breath before the conflict is raised to the next level. This gives the audience an opportunity to assimilate what it has experienced to this point so that it can better appreciate what is to come. At the bottom of the diagram is a straight line which indicates the lack of interactivity in the traditional three act structure, which is meant to be experienced from beginning to end without interruption.

The structure shown in Figure 2.2 is fractal in nature; that is, it can be usefully employed to described how action occurs at any level of a dramatic work. As Syd Field notes, “Every scene, like a sequence, act or an entire screenplay, has a definite beginning, middle, and end.” [36] Field goes on to add that the writer may not always choose to show each phase, but that they are always implicit at every level of a screenplay.

FIGURE 2.2

Single threaded, no choices (Platt, 1995)

(aka: traditional linear structure)

Dramatic narratives are built by the accumulation of detail created in specific conflicts in individual scenes which flow logically from those which came before and into those which follow. “The linear structure is at the same time progressive and additive. It’s a series of images and sounds, one after the other, revealing and unfolding information in time and space. Information builds upon information and we experience a passage through time.” [37]