“A film should have a beginning, a middle and an end…but not necessarily in that order.”

– attributed to director Jean-Luc Godard

Three Views of Structure

Aristotle’s method for analyzing theatre was simple: he read all the plays which had been written to his time and were available to him, looking for common features from which he could ascertain general rules of drama. I have been able to find three models for structuring interactive narrative, each of which was arrived at by a similar method.

“Interactive Entertainment: Who writes it? Who reads it? Who Needs it?”

In an article in Wired magazine, Charles Platt claims that there are five main types of story structure. The first is single-threaded, no choices. This is, of course, the traditional linear form of story with which we are all familiar (see Figure 2.1).

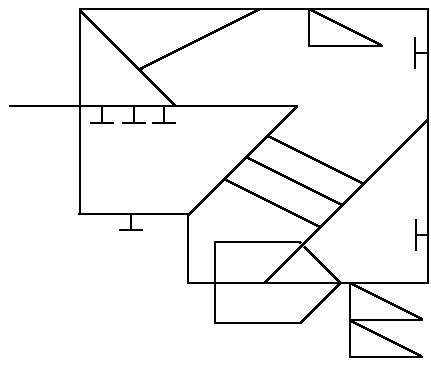

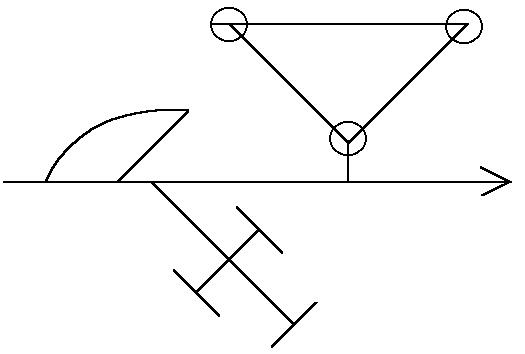

The second type of story is single-threaded with minor detours. In stories with this structure, “you start at the beginning, deviate through a few digressions, but always follow the same basic plot and arrive at the same ending” (see Figure 4.1). [71] An example of this type of structure might be a murder mystery where you can interview suspects in a variety of different orders, but where there is only one possible solution to the crime.

Figure 4.1

Cul-de-sac (Wimberley and Samsel)

Single-threaded, minor detours (Platt)

A) dead end forces participant to retrace his or her path

B) return to start of branch

C) Loop Back

D) Arena (replaces area of spine of story it passes over)

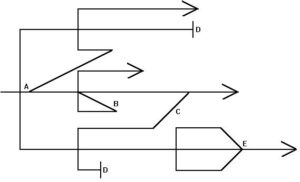

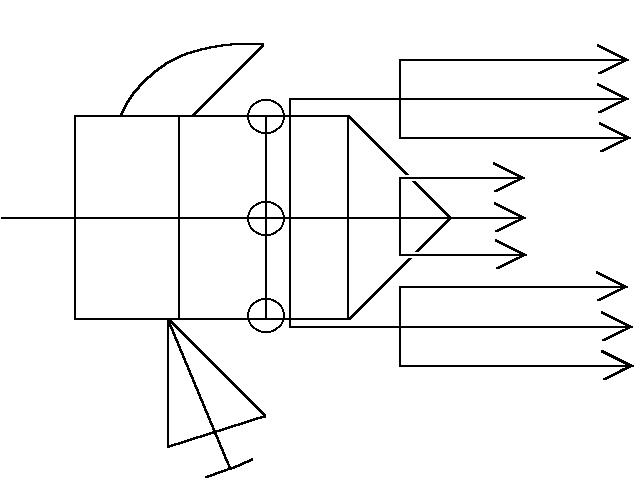

Multi-threaded with preset branch points is the third type of story. According to Platt, with this type of structure “you start at the beginning and respond to menus of options that take you through preprogrammed paths to a range of preset endings.” [72] Imagine a straight line, the story, which branches into three lines, which each branch into an additional three lines, and so on (see Figure 4.2). Platt calls this the “choose your own adventure” model. [73]

Say you are participating in a scene depicting an argument with your spouse. He or she makes an inflammatory remark, to which you can either respond in kind or ignore. If you respond in kind, your spouse escalates the argument by bringing up an irrelevant issue. You can either respond to the irrelevant issue or try to keep the argument focused on the real reason for the argument. If you ignore the initial inflammatory remark, your spouse calms down, and starts proclaiming his or her love for you. Now, you can respond in kind or, still harboring a grudge over the initial remark, respond coldly. As you can see, each of the decisions made in this story leads down distinct paths.

Related to this structural type is multi-threaded, unprompted. The structure, with a variety of different potential storylines, is similar to the third type. The main difference is that, whereas the third type of structure asks you where you want to take the story next, this structure follows where the participant leads without asking. “You make decisions at your own pace, without any nudging,” Platt explains. [74]

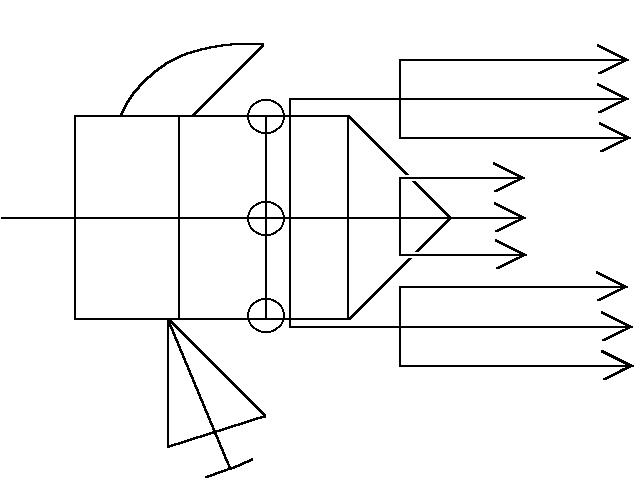

The final structure Platt describes is exploratory: “You are free to wander through a world; there are no pre-scripted scenes” (see Figure 4.3). [75] Unfortunately, Platt does not discuss how such a structure is created; his explanation that there are no pre-scripted scenes would seem to suggest that the writer is no longer necessary to the creative process, that all that is required is a designer and/or programmer. However, the example he chooses to illustrate his point (a CD-ROM by avant garde musicians The Residents called Freak Show), although it allows participants to freely explore its world, does contain scripted elements.

Ultimately, although a useful first step to understanding different interactive structures, Platt’s classifications seem simplistic, he makes one distinction which does not seem based on structure while missing a couple of distinctions which do and he doesn’t explore the different structures in any detail. For a better understanding of this phenomenon, we have to go to a different source.

“Screenwriting Structures for New Media”

In Creative Screenwriting magazine, Brian Sawyer and John Vourlis outline in greater detail different forms of interactive branching structures. Foregoing a description of linear narrative (which, I suppose, could be called “Non-branching”), they begin with an explanation of Simple Branching: “At certain points in the story, the viewer is presented with a list of options. Based on their choice, the story goes off in a new direction. The simplest type of Branching Story resembles a “Christmas tree” in structure. It begins with one scene which can then be followed by several possible scenes. Each of these scenes, in turn, can branch off to other scenes. Soon its structural diagram begins to resemble a Christmas tree turned on its side as its pathways begin to spread out…” [76] (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2

Simple Branching (Sawyer and Vourlis, 1995)

Multi-threaded, preset branch points (Platt)

Branching (Wimberley and Samsel)

A simple branching structure always moves the story forward in a straightforward manner. However, there are many circumstances in which you may want to go back to a previous scene, or jump over several scenes to one in the future, so a More Complex

Branching structure is necessary. “A story may have links that ‘loop’ back to previous scenes…” Sawyer and Vourlis write. “And a scene doesn’t necessarily have to link to its nearest neighbors. It can have links to scenes anywhere in the story, skipping across our story diagram to meet up with a scene on a distant branch. As we add more loops and links to our story, its structure will begin to look less and less like a Christmas tree and more like a web” (see Figure 4.4; for an example of a story with a Web-like structure, see “Case Study: Who Am I?, below). [77]

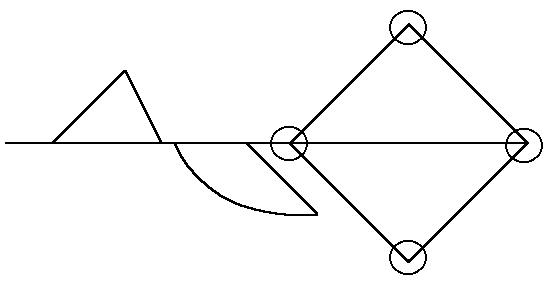

One very important structure which Platt doesn’t mention is Parallel Structure, which “links together several essentially ‘straight line’ conventional stories,” according to Sawyer and Vourlis. “At various points in the story, the viewer can choose to hop to the same point in a different rendition of the same story. For example, this structure could be used for an interactive product that allowed the viewer to watch a conventional story from start to finish, while having the power to switch between the perspectives of different characters along the way” (see Figure 4.5; for an example of a story with a parallel structure, see “Case Study: Close Encounters of the Nerd Kind,” below). [78]

These three structures deal with the flow of events; in creating works using them, the author decides where to put branches and where all the branches will lead. Interactivity notwithstanding, this type of writing is not all that different from traditional writing, where the author is concerned with juxtaposing scenes for maximum dramatic effect. However, the computer allows for still greater forms of interaction whose structures demand a different creative approach. These are Worlds and Simulations.

A World is a physical space in which the participant is allowed to wander freely. He or she may interact with other characters in the various spaces in which he or she may venture, or, by clicking a mouse on various objects within the different spaces, the participant may see reenacted scenes related to those objects. To create a World structure, rather than develop a diagram of the flow of events, therefore, the author must create a map of the various locations and objects which can be explored. Sawyer and Vourlis go on to point out that physical descriptions of the spaces in the world are only the first step: “The writer must also define the story. So, for each location, we must write the text of the scenes that might occur there” (see Figure 4.3). [79]

The CD-ROM game Myst is an example of a World structure. After a brief expository scene, the participant finds him or herself on a path with forks leading to a pair of different environments. Inside these environments are a lot of objects which, when the participant indicates them by clicking his or her mouse on them, reveal something about the world. These two environments lead out onto others; by exploring the world, the participant is, bit by bit, given the story of what happened there.

Finally, there are Simulations: “Simulations are generally the most interesting type of interactive product, but also the most complex. They don’t have a ‘branching’ flow, nor do they simply ‘map’ out a world. Instead, simulations assemble their stories dynamically, based on rules set down by the writer.” [80] In a normal story (even a regular branching story), the author would indicate that an object exists in a room so that a character could interact with it according to a script written by the author. In a world, the object would be in a room waiting to be discovered by an exploring participant; if the participant touched it, it would trigger a pre-scripted scene. In a Simulation, the object has characteristics of its own which come into play when the participant attempts to interact with it. As Sawyer and Vourlis explain: “To plan out a Simulation we first create a diagram that describes all of the entities in the story – the characters, the locations, the props, everything (we’ll call these ‘objects’). Next, for each object, we write ‘attributes’ and ‘rules’ to specify their properties and behavior.” [81] Fighter aircraft, tanks, battleships and other military hardware are typical of current simulations, possibly because simulations were funded by the military before they became a form of entertainment.

Figure 4.3

World (Sawyer and Vourlis)

Exploratory (Platt)

Free World (Wimberley and Samsel)

A) circles represent areas in which the participant can interact with objects and otherwise explore

Interactive Writer’s Handbook

While the two previous models of interactive narrative structure do not start from any preconceived ideas of what a narrative structure should be, Darryl Wimberley and Jon Samsel, authors of the Interactive Writer’s Handbook, insist that the new forms of narrative be built on the foundation of the old. Thus, they write: “An interactive screenplay can give a zillion opportunities for exploration to its users. But the interactive narrative, like the screenplay, has to have a ‘spine.’ That spine is a linear narrative which progresses from its initial propositions to a single narrative resolution.” [82] This spine, as Wimberley and Samsel describe it, is essentially the three-act structure of traditional theatre and cinema (although, curiously, they talk about “inserting three-act structure into interactivity” [83] rather than the other way around, which seems to be their actual intention). They refer to this central linear narrative as the Story Path.

As interactive designer Anne Hart put it, “you have to create one plot that provides the action in a cumulative way by using branches that return to the same basic outcome or plot. You need to create diversion and diversity among your alternatives.” [84}

Wimberley and Samsel’s description of simple branching structures is similar to that of the other two models: “…branching offers the most rudimentary course of action for the user to navigate from one sequence to another. In a typical branching story structure, the end-user is presented with several choices or options at a pre-designed fork or node in the program. Based on the user’s choice, the program or story then unfolds in that direction…” [85] They acknowledge that this is also known, as we have seen, as a Christmas Tree or Pyramid Structure (see Figure 4.2).

A second structure which Wimberley and Samsel describe is the Cul-de-sac: “Story Paths often branch away from the forward flow of the story into Cul-de-sacs, then return to the primary Story Path” (see Figure 4.1). [86] Imagine the straight line of the story with periodic branches where the participant can go off and interactively explore for a while, but must eventually return to the main story.

Wimberley and Samsel suggest two specific types of Cul-de-sac: Loop Backs and Arenas. “Sometimes the end-user will need to branch away from the forward flow of the Story Path and Loop Back to a previous scene,” they write. “Loop Backs are essentially links to previously viewed scenes.” [87] There may be an endless number of reasons for a participant to return to a previous scene, but let me give one example to clarify: suppose you go down a corridor but find the only door at the end locked. At the very least, you will want to return to the top of the corridor to continue moving forward through the building. In addition, if you have previously encountered a key on your journey, you may want to return to it to see if it unlocks the door. A Loop Back essentially takes you back (either to the top of the corridor, or the place where you first saw the key). Wimberley and Samsel claim that some people call Loop Backs Complex Branching or Webs, but, judging by the way previous models described those structures, their view of what they can be seems limited.

The other form a Cul-de-sac may take is an Arena: “Cul-de-sacs also provide a way for the writer to create scenes within scenes. Or, if the writer so chooses, to write alternative scenes which are able to co-exist along side or spin out from and return to the primary story…” [88] This sort of Cul-de-sac allows the participant to experience confrontations which, while not essential to the narrative, may nonetheless be entertaining to experience (this emphasis on confrontation is why the authors chose to call this form an Arena). Once done, the participant is returned to the point in the story where the choice was made, and it begins moving forward again. Alternative scenes, by way of contrast, actually replace a segment of the main story (but not in a way which compromises its forward momentum) and, therefore, end with the participant further along in the story than when he or she made the choice. An example might help clarify this: say you want something from a character. You are given a choice of whether the character willingly gives it to you (the main story) or the character initially refuses (the Arena Cul-de-sac). In the Cul-de-sac you explore as many alternative methods of getting the character to give you what you want as the author can devise, but the end must be the same: you will overcome the character’s initial reluctance and get what you want. At that point, you are returned to the main story where the character has given you what you want, bypassing the brief scene where he or she agrees to give it to you.

An essential feature of both forms of Cul-de-sac is that neither deviates from the spine of a linear narrative.

Free Worlds are Wimberley and Samsel’s term for what Sawyer and Vourlis called Worlds (see Figure 4.3). “While the structure for most Story Paths focus on the flow of interaction, the Story Path for a Free World relies on a matrix or map of interconnected scenes/worlds,” Wimberley and Samsel state. “By creating a map, the writer merely defines the physical space of the world. A matrix must then be created to show which worlds can connect to each other. To create a Free World story, a writer must actually create self-contained short stories or ‘novellas.’ Each self-contained world is connected by a thread…”89 By this logic, each explorable space within the world should contain its own narrative, with a beginning, middle and climax; they may share characters, situations and/or themes, thus gaining impact and import from each other, but they are not dependent upon each other. The connections between spaces are important more for the fact that they get the participant from one space to another than from the meaning (in terms of story, character or mood) that they may contain.

Wimberley and Samsel are dismissive of the Free Worlds structure when its primary effect is to allow the participant free range to explore: “If you are developing a Free World tour such as Myst, where exploration is the main objective, traditional story structure (aka Three Act Structure) is of little significance,” they claim, and refer to the subject no further. [90] Unlike the other models, Wimberley and Samsel’s model ingeniously melds the Free Worlds structure to the three act structure of traditional narrative: “Enter game at any point on upper nine-point ring. Solve three of the nine ‘items’ and move down one ring to the middle ring. There are nine new ‘items’ to solve on this ring. Solve three of those nine and move down to the lower inner ring. This ring also has nine ‘items’ to solve. Solve three of those ‘items’ and you complete Act I. You begin Act II at any point on the upper nine-point ring.” [91] You continue until you have solved nine items (which could be puzzles or confrontations with villains) on all three levels (Acts), at which point the experience is over. According to Wimberley and Samsel, this was the structure of the computer game version of the film Johnny Mnemonic (both of which were released in 1995). Note that at any level you are free to explore and determine which of the nine items you will attempt to solve.

Figure 4.4

Web (Sawyer and Vourlis)

“Harmonic Paths are perhaps the easiest structure for writers to comprehend,” Wimberley and Samsel write of the next type of structure. “Essentially, Harmonic Paths allow the writer to create a single linear narrative using multiple Story Paths which run parallel to the linear story.” [92] This is, of course, a restatement of Sawyer and Vourlis’ Parallel Structure (see Figure 4.5).

Finally, Wimberley and Samsel describe Simulations: “Simulations are the only Story Path structures that cannot coincide with a linear narrative structure. The flow or paths of a simulation title cannot be pre-planned…in Simulations, writers must first define all the major interactive elements in the program, then assign specific characteristics (attributes & conduct) to those elements.” [93] SimCity, where participants make choices about how to develop a city and the computer determines how it grows (or decays) in time based on the attributes of the building blocks the participant has chosen, as well as various other Maxis products (SimEarth, SimLife), are cited as examples of Simulations.

Figure 4.5

Parallel Structure (Sawyer and Vourlis)

Harmonic Paths (Wimberley and Samsel)

Case Study: Close Encounters of the Nerd Kind (Parallel Structure)

A young man and a young woman are sitting in a fancy restaurant. You can sort of tell by what they say and do what’s going on in their minds, but wouldn’t you like to know more directly what they’re thinking?

This is the basic premise of “Close Encounters of the Nerd Kind”, a text-based interactive short story. I originally wrote the story using a program called LinkWay Live!, although I am currently adapting it using HTML (HyperText Mark-up Language, the programming language used to create World Wide Web pages) in order to be able to post it on the World Wide Web. “Close Encounters” is an example of an interactive story which employs a parallel structure (see Figure 4.6).

The first level of the story tells a neutral, third-person account of the dinner. Choosing to move straight ahead, the participant can read this like a typical short story with no interruptions. However, to do so would be to miss a substantial part of the narrative.

The second and third levels contain the subjective views of the man and woman who are having dinner, their inner thoughts. The man’s thoughts reveal somebody who is very insecure, questioning the effects of everything he does. The woman’s thoughts reveal that she is disinterested in the meal and bored by the man’s attentions; unbeknownst to him, she has an ulterior motive for being there which has nothing to do with romance.

The fourth and final level contains an academic commentary on issues brought up through the action of the story. In the first fictional section, for instance, the restaurant is described as a place where people can use computers at their tables to communicate with others who are there; the corresponding text on the fourth level points out how such restaurants actually exist, and questions why people would go out to have such an experience when they could, with much less effort, communicate through computer networks from the comfort of their own homes. As you might expect, much of the commentary on this level deals with the structure of the story itself, especially how interactivity affects the esthetic experience of reading it.

Each level of the story can be followed on its own, just like the first. Thus, after reading the opening screen, which sets up the situation, it is possible to move to the second level and follow the subjective thoughts of the young man, or to the third level and follow the thoughts of the young woman, or to the final level where you can read the commentary straight through. Again, though, choosing a straight path would be to create a relatively poor experience, for it is through the interplay of the different levels of information that a rich, complex story plays itself out.

I encountered a problem when I was designing the structure of the work: wanting to keep things simple, connections were only between levels of the story (ie: from one to two or two to three), but you couldn’t jump a level (ie: from one to four), except from the bottom, where you could jump to the next screen on level one. In the original design, this meant that the young man’s story would always be the first one you jumped to when you dipped below the objective first level; I was worried this might privilege his point of view over the young woman’s, since you would have to go through his level to get to hers. I had to find a way of indicating that neither point of view was more legitimate than the other. A simple solution offered itself. By reversing the order so that the woman’s level was accessed from the first level in the second half of the story, and the man’s from hers, I gave her point of view equal weight with his. By crossing levels at the critical juncture, I was able to accomplish this while maintaining the integrity of the individual levels (by choosing a straight path, it was still possible to read his or her entire level). I could have accomplished the same thing by alternating his and her versions of events, but, again, in

the interests of keeping things simple, I decided to modify the parallel structure in this way.

Figure 4.6

The Parallel Structure of the interactive short story “Close Encounters of the Nerd Kind.”

The story contains one other structural addition worth noting. The title page, the first page one sees upon entering the program, contains several buttons which contain various types of information (personal information about the author, for instance, or copyright information for the story). There is also a button which tells the participant that it doesn’t actually do anything. If the participant clicks on this button, he or she goes to the same screen, except now the button gives a more strident message that the person is wasting his or her time. Click on this button, and the next screen menacingly tells the participant that he or she has been warned. Click on this button, and you return to the first version of the title page. The effect is (hopefully) humorous, but it also makes a serious point about employing interactivity for its own sake.

Finally, each page of the story has a “Home” button, which, when activated, takes the participant back to the first title page, and a “Quit” button, which allows the participant to exit the program. These are standard features of many interactive works.

“Close Encounters” illustrates some of the advantages of the parallel structure of interactive stories. It is very useful, for instance, in exploring different points of view arising from the same event. This has the effect of breaking down the concept of a single “true” story, a concept which, until recently, had pervaded much of modern literature and philosophical thought, replacing it with a series of interconnected points of view which, no matter how at variance they may be, have an equal claim to truth. This allows the creator to explore an event in much more detail, revealing hidden nuances and complexities, than has been the case in most traditional fiction.

Of course, narratives which contain multiple points of view exist in non-interactive media; there are many examples in twentieth century novels. However, for this short story, a linear text, alternating different sections using a different typeface or other means essentially foreign to common practice in the medium to differentiate between them, would be highly artificial. Moreover, navigating through the different sections would be time-consuming and, ultimately, frustrating for the participant. Interactive media offer a much better esthetic framework for this story than traditional media could.

Multiple points of view also allows the author to give the participant information which would not be readily available if he or she stuck with a single point of view. The man in my story cannot be expected to know the inner thoughts of the woman, or, indeed, how their encounter would look to a third party. (It also gives the creator the opportunity to speak directly to the audience, bypassing the story and characters, as I do on the fourth level of the story.)

Parallel structure, as the name implies, promotes parallels between different strands of a story, encouraging the participant to connect both similar and contrasting elements. In this way, an author can create comic effects by juxtaposing absurd or ironic scenes or parts of scenes.94 For example, in “Close Encounters,” the man makes assumptions about the date which we know from the woman’s strand of the story, are not true; this is used for ironic comic effect.

The strands of this story all arise out of one event, but this need not be the case. Parallel story structures can have interwoven strands with completely different characters acting out stories which do not have any common plot elements, or strands with characters in common which take place at different periods of time or combinations of these and other possible strands. In such cases, the parallels and contrasts might not be as obvious as in my story, which would force the participant to draw them his or herself, teasing out his or her own personal meaning.

In either case, recognizing the general thrust of the various strands in a parallel structure allows the participant more control of the experience. In my story, the participant can see the neutral version of an event, and then say to him or herself, “Gee, I wonder what the woman’s reaction to this will be?” or “Boy, that guy sure pulled a boneheaded move there – what was he thinking?” and go to the appropriate level. However, sussing out the structure of a work isn’t necessary to appreciate it; just wandering around and making connections should be sufficiently esthetically pleasing.

One final point: “Close Encounters of the Nerd Kind” was written before I had done any research into the structure of interactive narrative; I chose a structure which I intuitively felt would be most effective in telling the story I envisioned and in conveying the comic effects I hoped to create. Form followed function.

My Suggested Structures

As you can see, descriptions of narrative structure in the three models largely overlap: what Sawyer and Vourlis call Parallel Structure, Wimberley and Samsel call Harmonic Paths; a Cul-de-sac to Wimberley and Samsel is similar in nature to Platt’s “single-threaded, minor detours; and so on. This is to be expected: the authors were, after all, describing the same phenomena. Because of this, it is relatively easy to synthesize a single model of interactive narrative structures from the three we’ve already looked at.

I would start by looking at three levels of branching: Simple Branching (see Figure 4.2), More Complex Branching (see figure 4.7) and Webbed Branching (see figure 4.4). There might be any number of intermediary stages as we go from a simple branching structure to a highly complex branching structure, but these three should illustrate the point: interactivity can be seen as a continuum from simple to more complex forms. Arbitrary definitions (when does a simple branching structure become complex enough to be considered a web?) are less important than the overall idea of relative levels of interactivity.

Figure 4.7

More Complex Branching

A) branch returns to main story

B) branch returns to initial point of choice

C) branch moves to a place ahead in the story

D) dead ends

E) branches converge to a single storyline

In one sense, the greater the level of interactivity, the more control the participant has over the direction of the narrative. The corollary of this is that the greater the level of interactivity, the less control the author has over the direction of the narrative.

There is another way of looking at this question, however: inasmuch as the author creates the links which allow participants to make choices, it can be argued that the author actually is in control of the entire work. In this view, deciding to offer a branch to the participant is merely a creative decision, in the same way that choosing a specific adjective in poetry or designing a specific sequence of shots in film is a creative decision. I believe that both points of view have validity, revolving around different notions of what it means for an artist to control his or her work.

There are some problems associated with this type of branching. Sawyer and Vourlis point out, for instance, that at its simplest, “The Branching Structure can…be less efficient for storytelling as a complete narrative must be developed for each pathway a viewer might choose.” [95] Thus, a writer might have to create two hours worth of material for an experience which only lasts 20 or 30 minutes: “the game designer must write hundreds of scenes, only a few of which will be viewed in any one session of the game…” [96] On the other hand, this is a narrative which could hold a participant’s attention through several viewings, since choosing different paths would lead to substantially different experiences.

Simple branching is prone to the “exponential problem:” as the number of branches increases, the number of possible story paths grows much faster. As designer Gareth Rees explains, the exponential problem is “the combinatory explosion of the number of endings as the number of choice points goes up. With ten binary decision points, there are a thousand endings; with twenty, over a million. If we want to offer the reader frequent choice, or at least the illusion of frequent choice, how can we manage it?” [97]

Rees offers many possible solutions, none of which are entirely satisfactory. He suggests that several writers collaborating on a single work might be a satisfactory way of dealing with the explosion of paths leading to different endings. However, while it would spread the work around, making it feasible for such a work to be written (something seriously in doubt if one writer has to devise all the branches), it doesn’t deal with the central problem: offering sufficient choice in a simply branching interactive narrative would require too many paths/endings for a single narrative.

A second possible solution would be “to merge the continuations, to have several branches leading to the same conclusion.” [98] This would certainly help to cut down the number of possible paths; however, the cost would be to limit the participant’s sense of agency (see below for a further discussion of this issue), potentially leading to an unsatisfactory experience. As Rees himself notes, “…it isn’t clear what the point is of writing a story in tree form if all the decisions are fake ones that eventually lead to the same place in the narrative.” [99]

One possible solution to the exponential problem would be to combine other forms with simple branching so that some narrative paths merge, but others lead to different conclusions. As long as some of the decisions did, in fact, affect the course of the narrative, the participant would be empowered by the interactivity of the work because, until he or she had experienced it, he or she would not know which decisions would affect the outcome of the story and would, therefore, have to act as though all of them did.

A different criticism of branching structures suggested by Platt is that “A session of the game may contain some great twists and can lead to a satisfying climax — or it can be a total bummer…you never know what to expect.” [100] This criticism could be directed against interactive structures in general; indeed, this is the risk one takes with any work of art. Platt’s specific complaint, however, is that different branches in the same work, because they offer different experiences, may lead to widely divergent levels of pleasure for a participant. As Marie-Laure Ryan explains, rather than “experiencing exhilaration at the freedom of ‘co-creating’ the text…the reader may feel like a rat trapped in a maze, blindly trying choices that lead to dead-ends, take him back to previously visited points, or abandon a storyline that was slowly beginning to create interest. The best way to prevent this feeling of entrapment, it seems to me, would be to make the results of choices reasonably predictable, as they should be in simulative VR, so that the reader would learn the laws of the maze and become an expert at finding his way even in new territory. But if the reader becomes an expert at running the maze, he may become immersed in a specific story-line or forget – or deliberately avoid – all other possibilities. He would then revert to a linear mode of reading and sacrifice the freedom of interactivity.” [101] In addition, perverse participants would disregard the clues, although doing so would lead to a linear reading anyway. One possible solution would be to create local pockets of order, each with a different set of rules to be discovered.

However, ultimately an artist can only be held responsible for what is in his or her control; by bringing all of her or his artistic talents to bear, the author should be able to maintain a level of creativity in all branches of his or her narrative. In a comedy, all branches should have a similar potential to make a participant laugh; in a drama, each branch should have a similar potential to engage a participant emotionally; and so on. All the artist can do is create the potential; how the participant perceives the work is out of the artist’s control.

Wimberley and Samsel, using the example of an early interactive film, offer a different criticism of simple branching structures: “[Controlled Entropy’s] I’m Your Man was a film released and billed as an ‘interactive movie.’ The filmmakers provided a means for the audience to vote on various outcomes spun out of the movie’s mystery plot. The problem was — A single, unified narrative could not support three conclusions. Multiple conclusions can’t be sustained unless they are contrived or worse — that the ‘evidence’ supplied in earlier scenes is ignored or amended.” [102] For the most part, their point is well-taken: as we saw earlier, the forward movement of a story should slowly close down all possibilities until there is only one possible conclusion, the one which we experience. I’m Your Man violated that basic point. However, it seems to do so by poorly structuring its choices. Instead of offering three endings after the body of the film had been set, if choices were allowed from virtually the beginning, three distinct story lines (which shared a variety of scenes) could have been developed, each with its own flying wedge which would have led to a satisfying conclusion. (Unlike Wimberley and Samsel, I can find no theoretical reason to dismiss the possibility that multiple endings can be esthetically acceptable in interactive media. In pointing out the inadequacies of one poorly structured work, they have not made the general case that all works with a similar structure are similarly flawed.)

Because of their commitment to the idea of a single narrative through line to which interactivity is added, Wimberley and Samsel suggest a couple of odd methods for structuring branched interactive narratives. In the first, each choice of branch leads to the same result. So, if you want something from a character, you are given a number of choices of how to get it, but each inevitably leads to your success. The problem with this approach is that if the choices offered in the course of a work do not make a difference to the direction of the narrative, the work cannot be said to be truly interactive.

This judgment revolves around the concept of agency. As Brenda Laurel defines it, “the noun ‘agent’ [means] one who initiates action, a definition consistent with Aristotle’s use of the concept in the Poetics” [103] For interactivity to be esthetically pleasing, for it to be more than a frill laid over traditional narrative structures, the participant must feel as though she or he is actively determining the course of events in the narrative. “I posited that interactivity exists on a continuum that could be characterized by three variables: frequency (how often you could interact), range (how many choices were available), and significance (how much the choices really affected matters),” Laurel wrote, adding, “…There is another, more rudimentary measure of interactivity: You either feel yourself to be participating in the ongoing action of the representation or you don’t.” [104] A skillful artist could develop a totally engaging interactive narrative in which all the choices lead to the same conclusion, but anything less than totally engagement would run the risk of alienating a participant perceptive enough to realize that the choices weren’t really choices at all.

The other possible method of retaining the three act structure within an interactive framework is to offer the participant any number of choices at preset branch points, only one of which moves the narrative forward. If you require something of a character, for instance, you may be given a choice of three approaches which will not lead to your obtaining what you need and one which will. In this way, a “Critical Path” through the work (the one in which only the right choices are made) exists; such a path can have a linear narrative structure. Again, in skillful hands this could lead to a pleasing experience; however, a practical problem with this approach is that if the participant doesn’t find the right choice relatively quickly, he or she will become frustrated and abandon the work. [105]

Each of the three models allows for a Parallel Structure (see Figure 4.5) in Platt’s model, it is another form of multi-threaded narrative with pre-set branch points. This structure has a single narrative which the participant can experience, but that seems an impoverished use of interactivity. By making connections between different narrative threads, the participant can create a rich web of meaning, which, in the hands of a creative storyteller, can be an engaging and satisfying esthetic experience.

Although I have included the Cul-de-sac (see Figure 4.1), I find it a highly problematic structure. Here, again, I would point out that the participant’s interaction with the work must offer meaningful choices which give the participant a sense of her or his own agency. If the Cul-de-sacs are too easily perceived as diversions which do not affect the narrative in any appreciable way, the participant is likely to be dissatisfied with the experience. In addition, if they are not directly tied to the forward motion of the plot, they violate Aristotle’s unity of action. (On the other hand, used skillfully, the Cul-de-sacs themselves, such as Loop Backs and Arenas, are useful tools which can be added to any structure to increase the amount of interactivity in it.)

It may not seem so at first, but Aristotle’s idea that you should only include what is relevant to the telling of a story in a work of art will actually apply to any well crafted interactive work of fiction. Although the information in some threads may not fit into the storyline developed in others, all scenes should be relevant to the storylines which develop if the participant chooses them. Consider the simple branching structure: follow any series of branches to the end of Figure 4.2 and, if the story is properly constructed, every scene you have experienced should be relevant to that story. Another thread will have scenes which wouldn’t have been relevant to the first; however, if you follow the branches in that thread, all of them should be relevant to it. There is no reason to believe that this might not hold true for any interactive narrative structure, no matter how complex.

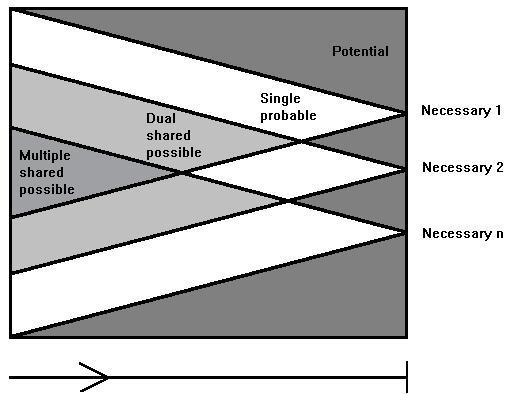

A similar argument can be made that the three act structure (with its rising action, as in Figure 2.2 or Brenda Laurel’s flying wedge, Figure 2.1) can be preserved within any interactive structure we have considered to this point by ensuring that every thread follows it. Here, rather than having all of the possibilities narrow to a single necessary conclusion, narrowing possibilities in different ways would lead to different conclusions, though each conclusion would be a necessary outgrowth of the causal chain of scenes which preceded it (see Figure 4.8). Which conclusion was experienced would, of course, depend upon the choices the participant made as the work unfolded.

An example might help clarify this. If we were developing an interactive mystery story, the basic setting (say, a spooky old house) and the main characters (the victim and three suspects, A, B and C) would be common to all of the story threads, what I have called the multiple shared possible. As the story progressed, two threads would emerge, one in which A and B were heavily favoured suspects, the other in which B and C were heavily favoured suspects. The thread where A and B were suspects would share scenes in common, although leading to two different probable outcomes, one where A was the murderer and the other where B was the murderer. At the point where a single probable outcome became apparent, each thread would need its own unique scenes to bring it to the necessary conclusion. The thread involving B and C as suspects would, of course, have a similar structure.

Figure 4.8

The “Flying Wedge” adapted to interactive forms.

This explanation distorts the true possibilities of interactive narratives for the sake of simplicity. For one thing, there may be any number of narrative threads leading to any number of necessary conclusions (noted, in Figure 4.8, as Necessaryn), not merely three; although more complex than my simple murder mystery example, such a plot would follow the same basic structure. For another thing, shared elements likely will not come in discrete sections, as Figure 4.8 might lead you to believe: for example a final scene where the detective shares a joke with the police inspector might be common to all

threads of the story regardless of who the murderer turned out to be. The important consideration is that each scene, regardless of the number of threads in which it appears, is part of the progression from possible story line to probable story line to necessary conclusion in each of them. In a similar vein, Figure 4.8 might leave the erroneous impression that each thread is approximately the same size or length. This need not be the case; some threads might lead rapidly to a resolution, while other takes considerably more time.

These caveats aside, adapting the Flying Wedge to interactive structures helps us better understand how they can employ traditional structures. This is more evidence against Wimberley and Samsel’s argument that interactivity MUST be added to an otherwise linear story in order to preserve the three act structure.

However, as we shall see, the three act structure is not always the best one to employ in interactive media – although many stories will benefit from it, there is a sense that many theorists are attempting to impose linear structure on what is essentially an associative medium. With a potentially complex story structure such as a web, repeatedly going back over a specific scene (each time armed with the knowledge of a little bit more of the story), may make for a more esthetically pleasing experience than simply going through the scene in its place in a linear narrative. For this reason, although an artist CAN use any of these structures to tell traditional stories, the artist should not feel he or she MUST – the needs of the story the artist wants to tell and the esthetic experience the artist wants to create should determine structure.

Worlds (see Figure 4.3) and especially Simulations offer a different level of interactivity than the previous structures. As we have seen, Worlds allow the participant to wander freely, interacting with objects and other characters, while Simulations require the creation of objects with characteristics which determine the action. At this point, the difference between an author and a designer/programmer blurs.

Platt argues that these are the only forms which will provide truly satisfying interactive experiences, and that all of the other narrative structures will prove to be dramatic failures. “The three strengths of interactive entertainment defined by Janet Murray – immersion, rapture and agency – are all maximized when constraints of plot and structure are tossed aside… Story structure would diminish…freedom and add an element of artificiality that might interfere with the feeling of immersion.”106 Immersion, the feeling that one is actually “inside” the experience, rapture, the pleasure one gets from a highly satisfying esthetic experience, and agency are all parts of the interactive experience. However, Platt elevates immersion over the other two factors; without knowing why he takes this position, it’s difficult to critique it (at the current level of interactive media, agency would seem to me to be the more critical quality since interactive input devices, by their nature, work against a sense of immersion). I would suggest that an effective balance of the three qualities can be achieved in a variety of different interactive narrative structures.

Although a couple of the models allow for combinations of the different structures, none of the authors actually consider what forms such hybrids might take. I can see at least three. In the first, Serial Hybrids (see Figure 4.9) two or more structures follow one another in a linear fashion. With Contained Hybrids (see Figure 4.10), one or more structures is totally contained within a different structure. Finally, Complex Hybrids (see Figure 4.11) involve two or more structures in complicated relationships which cannot be reduced to one of the previous hybrid forms.

In developing these models, I have rejected Wimberley and Samsel’s claim that the three act structure must be the basis for interactive narrative. A simple demonstration will hopefully show why. Suppose we add a single Loop Back to the traditional narrative (see Figure 4.12). In this case, we go from a point in Act Three backwards to a point in Act Two. We will, thus, experience the climax from Act Two for a second time. While it is true that the dramatic structure remains basically linear, the participant’s experience of the work has radically changed. The slow building towards a climax which is the hallmark of traditional narrative has been interrupted, the flying wedge can no longer be experienced. As more interactive branches are added, maintaining the emotional impact of the Introduction-Complication-Resolution form becomes increasingly difficult, even if the basic structure of the work is linear. It seems to me that Wimberley and Samsel analyze interactivity from the stand-point of adapting it to traditional structures rather than seeing what structures it is capable of supporting, and how best to craft those structures into a compelling esthetic experience. In so doing, they put unnecessary limits on what can be done with interactive narratives.

Figure 4.9

Serial Hybrid

(Cul-de-sac followed by worlds)

They claim, for instance, that “Simple interactivity might be okay for your average interactive training title, but it won’t draw the audience into a complex interactive drama.” [107] Using traditional narrative structure as their model, this would seem to be a reasonable conclusion. If, however, we assume that every medium of communications develops its own narrative forms (as I have from the beginning), then this statement stands unproven. In fact, there is reason to believe that a simple branching structure can result in a complex, emotionally satisfying interactive drama – if, as we have seen, each thread was constructed so that it had its own flying wedge, building dramatic tension leading to its own climax and resolution. Ultimately, time and experience will show us which forms of interactive structure are suited to which types of stories; for the time being, I prefer to be optimistic about the possibilities.

Figure 4.10

Contained Hybrid

(Worlds within a Cul-de sac)

In any case, these are some models for narrative structure which can be perceived at this time. Although simple, very complex structures can quickly evolve out of them. I have no doubt that other structures which cannot be conceived of at this point in the history of interactive media will emerge in the future. However, whatever structures may be created (discovered?) in the future, I feel that a simple rule will always be applicable to creating interactive narrative: form must follow function. That is, the kind of story you want to tell and the ideas you want to explore should determine the interactive structure of your narrative.

Who Am I? (Web Structure)

“Who Am I?” is an interactive short story which I have designed but not yet implemented. In the middle of the screen will be a question mark in a circle. It is surrounded by seven images; clicking on an image will take you to a short written passage related to the image which reveals something about the character. A picture of a park, for instance, will lead to the passage: “On a nice summer’s day, I like to go to the park and play ball or toss around a frisbee or just hang out and see what everybody else is doing;” while a picture of a steak will lead to the passage: “Personally, I like meat. But some people around here are so worried about my health that they force me to eat cereal and – uggh! – vegetables. Vegetables! Is it any wonder I get short-tempered and bark at them?” When the participant has accessed all seven of the texts behind the images, he or she can then click on the question mark, which will lead to a picture of a family dog, the subject of the story.

Although simple, “Who Am I?” displays the characteristics of a web at the furthest end of the continuum of interactivity. The seven pages can be accessed in any order. There cannot, therefore, be a linear narrative; instead, the story allows the participant to explore a character, building an increasingly complex picture as more pages are read. The ending will hopefully come as a surprise, making the participant want to return to some of the previous pages to see how their ambiguous messages could be interpreted as referring to both a human being and a pet.

Complex Hybrid

(combines Parallel Structure, Cul-de-sac, Worlds and Simple Branching)

Directing the participant without relaying instructions on how to use the work is important. After all, we don’t need instructions on how to watch a particular television program or read a specific book. “Who Am I?” was originally designed to be implemented on LinkWay Live! such that clicking on the question mark wouldn’t do anything until all seven pages around it had been read. To encourage this, after a page had been read and the participant returned to the opening screen, the image associated with that page had disappeared. If you accessed all seven pages, the only image left on the opening screen would be the question mark; it was only then that it became a button which, when clicked, transported the participant to the final page.

Using this design, I had to create a screen with every combination of the seven images. Imagine that the person starts by choosing image six; when he or she returns to the main screen, all the images except six are there. Now, if the person then chooses image three, all the images but six and three will be available on the main screen. And so on. But the person could also choose image five, followed by image one; or image seven, followed by image two; or… In order to map all the different possible paths, I created a complex diagram showing what happens when you eliminate numbers one at a time. In fact, there are simple mathematical formulae to deal with such problems, but I did not know them, nor would I expect a writer to. At first, it seemed like I would require an impossibly large number of screens in order to accommodate every possible path; however, I soon realized that the number of unique screens was much smaller because many paths lead to the same screen. Choosing screens one, three and five, for instance, take you to the same place as choosing screens five, one and then three. This made the number of screens necessary much more manageable.

In HTML, designing “Who Am I?” would be much simpler. A live image (one which leads to something else when clicked on) has a thin blue line around it; on the opening screen, the seven images would be so rendered while the question mark would not, indicating to the participant what he or she should do next. A small program would have to be written to make the question mark active after all the other images had been accessed; thus, it would have a thin blue line around it which would tell the participant that it was now ready to be used. In addition, once an image has been accessed, the line turns from blue to orange; it wouldn’t be necessary to eliminate images to show that they had already been used. The participant would just return to the opening screen after reading each page.

Web structured interactive works, where the participant is free to explore a wide variety of potential paths through a series of dramatic encounters, pose a unique problem: how the participant can navigate through the information so that the experience is meaningful and esthetically satisfying. Moving through a web is similar to walking across a desert: without any reference points, it is difficult to know how far you have travelled, how far you have to go before you reach the end or, indeed, if the direction in which you are heading will lead anywhere. And, like a wanderer in the desert, it is possible to move through a web in circles, constantly coming back to where you have been before. The problem of navigating through a web can lead the participant to a very frustrating experience.

With other interactive structures, the forward movement of the plot gives the participant a sense of direction; if the story appears to be stalling, the participant can always choose to take it in a different direction. The smaller the units in the web, and the larger the number of connections between them, the more difficult it is to create a story with a forward momentum. Webs work better with the accumulation of information and esthetic effects (as demonstrated by “Who Am I?”). For this reason, another method of navigation must be found.

In non-fictional hypertext, a map is generally employed to help a user navigate a space with a lot of information. Anybody who has used a word processor is familiar with a simple map: a list of files in a folder. On the World Wide Web, which is a largely visual medium, maps are usually visual metaphors for the kind of information contained on the site (literally including, not surprisingly, maps). In a sense, the visual structure of “Who Am I?” is a map: the seven images show the user how big the work is; as they are eliminated, the user is constantly updated on how much is left to see and where it can be found. However, this kind of map works in this piece because it is relatively small; a work with a web structure containing hundreds of screens could not realistically be designed this way.

One possible way of using a map for a large fictional web would be to subdivide it into smaller clumps of pages and links, analogous to the chapters of a book, each of which would have its own conceptual map. In order to help navigate these, an overall conceptual map would be helpful (this is similar to the directory/sub-directory/file

structure of most computers). The sub-divisions could be more or less self-contained if, for example, they dealt with scenes or conflicts which took place at different times or in different places. However, self-contained sub-divisions might defeat the creator’s purpose of interconnecting the various parts of the story; for some stories, it would be advisable to have connections between individual pages in different sub-divisions. But then, the participant could be surprised (and disoriented) by finding him or herself navigating through a different map than the one by which he or she entered the story, although experience with this might make it easier for participants to accept.

Another possible solution to the problem of navigating through a web might be to flag specific pages. This could be as simple as highlighting a key word or phrase within the text of the page, giving it a word or a phrase as a title or at the bottom of the page, or using a picture or graphic; in a visual work such as an interactive film, a title card could contain such a flag, or it could be woven into the dialogue or visual images in the scene. Flags would be mnemonic devices for the participant; seeing one, he or she would be reminded that he or she had accessed the page before and, if he or she remembered the route previously traveled, could choose a different path. The more pages of a work which contain flags, the more likely the participant is to recognize old paths and navigate new ones.

Still, the participant may not recall the route previously traveled. So, rather than create flags as permanent parts of specific pages, it might be advisable to flag pages after they have been accessed. A check mark or simple word or phrase might appear in a corner of a page the second and subsequent times a participant accessed it. Since each page along the path the person has chosen would be similarly flagged, the person would not have to remember every choice he or she had made; if three or four pages in a row were flagged, the participant would know that he or she had gone down this path and should choose another direction.

Figure 4.12

Traditional narrative structure with a Loop Back to an earlier part of the story.

In fact, it would be possible to color code each page to indicate how often a participant had accessed it. On first reading, the background color would be, say, grey. On second reading, light blue; on third, pink; on fourth, orange; and so on. (The text and/or graphics would have to change so that they could be read easily against the new background.) The participant would have a subtle clue as to how often he or she had seen a specific page or even gone down a specific path, and could adjust his or her choices accordingly.

One other possible solution to the problem of navigation would be to program a work so that a person could not follow a link previously taken. Closing access to previously seen pages would keep the participant moving in new directions, seeing new parts of the story. On the other hand, it would mean some parts of the story would be inaccessible in some readings. Suppose you had a choice on page A which branched to either page B or page C. If you chose to follow the link to page B, you could not go to page C because you would not be allowed to return to page A to make the other choice. Making sure that each page had several entrance and/or exit points would mitigate this problem somewhat, but it would not entirely eliminate it. If you had information which was crucial to the esthetic appreciation of the work, you would have to place it at the center of the web, with the most entrance/exit points to ensure that it was accessed. Another way of ensuring that important information was accessed would be to have it appear on more than one page (in computer circles, this is known as building in redundancy); this would increase the number of paths which led to it, increasing the chance that it would be seen. Repetition also has esthetic properties which could be exploited: exact repetition of a dramatic moment gives it increased emotional weight; repeating a scene from different points of view, while containing more or less the same information, increases the richness of the experience.

If the participant was forced by the program to always choose a new path, it would be possible to have a counter on the screen which indicated how much of the story had been experienced (which, by inference, would indicate how much was left). This could be represented as a percentage of the pages in the work (“You have read 37%.”), as a comparison of pages read to total pages (“You have read 27 of 156 pages.”) or as an icon which is slowly filled in as pages are read. (In a more visually oriented work, the number of shots or sequences could be used as the basis of measurement.) It is possible to have a counter in stories where paths are not circumscribed after they have been experienced, but this would only indicate how much of the story has been accessed. Because the person could theoretically keep going over the same paths forever, a counter could not tell a participant how much of the story was still to be experienced.

These are preliminary thoughts on possible solutions to the problem of navigating through a web of fiction. Experience will undoubtedly suggest others. Whether a creator uses maps, flags, counters or some other device yet to be considered, it is important that the device be diegetic to the story being told. In “Who Am I?”, the map is an important part of the esthetic experience of the story. No matter how well-designed a navigational device is, if it takes the participant out of the experience, if it destroys the willing suspension of disbelief, it will be an esthetic failure. Here, as with other aspects of interactive storytelling, the technical problems and their solutions must be shaped to fit the nature of the story to be told; in short — and, please, stop me if you’ve heard this one before – form must follow function.

A Different Approach to Story Structure

Most of the structures we have looked at have fixed narrative elements through which the participant navigates (by choosing path 3C, you see scene 27F, which never changes). Some people have argued that this is not true interactivity because user participation cannot change most of the experience. (I would argue that, on the continuum of interactivity, such works are certainly more interactive than traditional media; otherwise, arguments about what constitutes “true” interactivity are a waste of time.) Simulations, which require and are sensitive to continuous participant input, seem more interactive. This leads to the question: is it possible to use the principles of simulations in dramatic works?

Walt Freitag, founder of Daedalus Arts thinks it is. His approach to structuring narratives is based on the concept of “fractal story elements:” “small, isolated plot pieces that remain associatively linked even though other events can come between them during the story. They’re flexible enough to be relocated at different places in the story and still make sense.” [108] Rather than break the action down into scenes, each scene would be broken down into bits of information (sometimes referred to as plot points, a more

general definition of the term than screenwriting guru Syd Field would approve of); each of these bits of information would be described in the computer’s memory, and they would come with descriptions of the circumstances in which they could be injected into the story. Then, as you interacted with various characters at various locations, the story would actually be created in real time by the computer.

“A more interesting approach [to designing an interactive work] would be to create a rich set of plot fragments and character behaviors which may be assembled by the computer to allow the creation of new stories each time the program is used,” explains Julian Arnold. “In the finished product, the individual elements of the story can combine in new and wonderful ways not anticipated by the author or programmer.” [109] In addition to the fragments, the computer would also require a “plot parser,” a program which would recognize when the elements are coming together in a dramatic way; if the different elements the participant triggered threatened to make no sense, this program would inject elements which would ensure that some dramatic structure was developed.

The technology to create such a story out of basic elements probably exists now or, if not, will be created in the near future. However, there is very little theoretical knowledge of what might constitute a proper fractal story element, or how to combine such elements in esthetically pleasing ways. This could prove to be a fertile area of research in the future.