Introduction

We all know jokes about action/adventure films: “Yeah, sure, the last feature length action script I wrote contained three pages of dialogue and sixty-five pages of scene description!” Ha ha. There is, however, far more to action films than, well, action. Between the stunts, human beings have to be introduced to the audience, which must identify with them or find some other reason to care what happens to them. If the audience has no emotion invested in the characters, the quality of the effects will not be enough for them to enjoy the film.

In a similar fashion, it isn’t sufficient, in a narrative film, to string together a series of action stunts and effects; they have to be driven, however minimally, by an engaging story. (In fact, videos of violence unsullied by plot or character have circulated for years; that most people still seem to prefer their action in a narrative setting suggests that plot and character should not be considered afterthoughts, but are an integral part of any well-crafted action film.)

Once we accept the need for well-drawn characters and an engaging plot, the question becomes how best to mix these elements together with action to create the most entertaining film possible. Many writers believe that adding humour to their action/adventure screenplay will make it more successful, that adding laughs to the thrills is a winning formula. Most action films now released contain some attempts at humour; it is rare to see an action film without them. In most cases, this is more a matter of faith than clear intention, because few filmmakers have bothered to ask themselves the key question on this issue.

Does humour actually work within the context of an action film?

I believe it can. In very specific circumstances…

Humour and Action are Completely Incompatible

Theory is very clear on this point. There are at least three areas in which humour and action compete rather than complement each other: in the way the viewer’s body reacts to them; in how they play in foreign markets; and in the nature of the comic hero.

Start with the least important concern for the writer: how films play in foreign markets. Action/adventure films are typically very popular in foreign markets, earning a substantial amount of their revenue from them. The reason is simple and obvious: explosions and other effects, being visual, carry more or less the same meaning no matter from what culture they are viewed.

For the most part, this is not true of humour. Purely physical humour, because it is also visual, usually travels very well. But puns or any other sort of wordplay are difficult to translate into other languages. Most jokes touch on aspects of culture which won’t be appreciated by people from a different culture (especially in these post-modern times where ironic references to popular culture dominate comedy). An appreciation of satire requires knowledge of the institution being satirized. Even absurdist comedy will not work in foreign countries where the nature of reality may be thought of in different terms. [1]

In a perfect world, this would not be a consideration for a screenwriter; however, when you dance with a studio, it calls the tune. The higher the budget for your action/adventure film, the more important foreign markets become, and the more you should stay away from humour likely to alienate foreign audiences.

There are other, more immediate concerns for an action writer who wants to incorporate humour into her or his screenplay. Have you ever felt light-headed after you’ve laughed a lot? Laughter causes endorphins to be released in your brain. Endorphins are the body’s natural painkillers; they are usually released when you suffer a physical trauma (such as, say, a gunshot wound). Their effect is to block the immediate pain, and slowly let you come back to reality. [2]

By way of contrast, we are all familiar with what happens when confronted by an effective action sequence: our heart rate speeds up, our breathing may quicken, etc. One of the main effects of an action sequence is to pump adrenalin into our system. Adrenalin is the “fight or flight” chemical: it is released into our bodies when we are confronted with danger, giving us an extra jolt of energy with which we can either confront the danger or run from it.

These two physical reactions cannot be sustained at the same time, since they push the body in two completely different directions. A writer who tries to combine comedy and action without taking this into account will inevitably create an ineffective mush. As we shall see below, however, these competing reactions can be used to great effect.

Finally, there is the nature of the comic hero, or fool. In ancient tribes, the fool was originally a person with a physical deformity or mental handicap who was kept by royalty for luck. The mentally handicapped fools were allowed to speak their mind, and often used this freedom to expose the weaknesses of their betters. In the Middle Ages, fooling became a profession for those who were not handicapped, although the tradition of using their wits (in both senses of the word) to expose the venality and hypocrisy of the wealthy and high-born continued. [3] This tradition remains throughout comedy to this day.

Whereas the comic hero is given licence to expose the corruption within the ruling elite of his society, the action hero’s purpose is to support the social order. A typical action film will begin with an act which threatens society (the commission of a crime, for instance, or the stealing of a state secret); the action hero is dispatched to deal with the threat (the detective must apprehend the criminal, the spy must get back the secret before it is used agains the state). While these two different character traits are not completely incompatible, a writer should be wary of them because they can easily work at cross-purposes.

In keeping with its origins as a mentally handicapped person, the fool figure is invariably “innocent,” not knowledgeable about the ways of society. It is for this reason that we are more likely to laugh at the folly of clowns, even if we are the butt of their jokes, than to become offended. Film has a long history of such fools, from silent stars Charlie Chaplin (as the “Tramp”), Buster Keaton, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle and Harry Langdon through Laurel and Hardy and Chauncey Gardiner in Being There right up to Forrest Gump.

The action hero, on the other hand, must negotiate a complex series of social interactions (interrogating witnesses or setting up secret meetings). To carry out its purpose successfully, the action hero must understand how society works. In noir films, in particular, the hero usually has a world-weariness which makes humour highly inappropriate.

In addition, although innocent, the fool is virtually invulnerable to harm. The original fools were thought to be able to communicate with god, and were, therefore, under his protection (a major reason why kings were reluctant to behead fools no matter how offensive their humour). Our modern comics, although calculating in their foolishness, assume the same invulnerability: nobody really believes that, say, the Ghostbusters are ever in serious enough danger that one of them could actually die.

With the action hero, of course, we must believe in the reality of the danger which we are watching, or else much of the thrill is lost. As if to drive home the hero’s vulnerability, many action films will have the first encounter between the hero and villian end with he hero all but vanquished. One other method of emphasizing the potential danger for the hero is to have secondary characters beaten or killed. To be sure, we want the hero to triumph, for good to soundly kick evil’s butt; however, if the hero can’t be hurt, the fight isn’t fair, and our enjoyment of it will be seriously diminished.

Finally, in keeping with its innocent nature, the fool is often not an actor in his or her story as much as a character who is acted upon by the other characters (or sometimes, as with Keaton, the physical world). This is the opposite of the action hero, who, of course, must act, and act with a definite sense of purpose if the initial situation (crime, stolen secret, whatever) is to be resolved.

Many writers feel a great temptation to add humour to an action/adventure screenplay to make it more appealing. However, because humour tends to undermine the character of the action hero, it should not be used indiscriminately. The James Bond films are a cautionary tale to this effect. In the first couple, Sean Connery portrays Bond as a serious spy. As the series continues, however, he is given more comic lines, to the point where the character is no longer credible as an action hero by the time Roger Moore is called upon to take over the role.

Because they are at such odds with each other, humour and action don’t often mix well; if you don’t end up with a muddled mess, you usually have a film where one dominates the other. Beverly Hills Cop is basically a comedy which has a small number of action sequences (although they also contain humour, so it’s hard to take them seriously as action sequences). Apparently, star Eddie Murphy wanted to change his image as an actor, so Beverly Hills Cop 2 contains far less humour and much more action; it is a complete 180 degree reversal from the first film, an action film with a little bit of humour. (The third film in the series, where more of a balance between action and comedy was attempted, wasn’t effective at either.)

There is nothing wrong with a comedy with a little action or an action film with a little comedy, as long as that is what you set out to do and you know how far to mix them without one element competing with the other. If you want to mix them in more or less equal measure so that they do not undermine each other, a much more difficult task, you will have to be very aware of what you are doing.

The Good, The Bat and The Ugly

Mistletoe can be deadly if you eat it.

But a kiss can be deadlier if you mean it…

Oh god…does this mean we have to fight now? [4]

Okay, according to the theory, it should be impossible to mix comedy with action so that both are effective. Fortunately, theory and practice are like twins looking into different funhouse mirrors: their images don’t always match up. In fact, there are circumstances where the two can be used effectively in the same film, but they are very specific.

Consider the above dialogue from Batman Returns. [5] In their alter-egos as the Catwoman and the Batman, these two characters exchanged the first two lines in the midst of a fight. The lines, repeated at a fancy dress ball, finally make the two, who have developed a romantic relationship in their private personae, realize that they have been fighting each other. Selena Kyle’s final line is funny because it unexpectedly upsets the convention in super-hero movies (taken from the original comic books) that the hero and villain can always identify each other and, once they have, must immediately start to fight.

Two important elements should be noted about this scene. One is that it arises naturally out of the workings of the plot. The story has developed to this point by keeping knowledge of the secret identities of the two characters out of each other’s hands; their relationship has built to this moment of revelation.

The other thing to note is that the line is appropriate to Selena Kyle’s character. At the beginning of the film, she is a mousy secretary pushed around by everybody around her. Taking on the Catwoman persona allows her to release the strength of character which she does not feel she has as Selena Kyle, to the point where her confidence spills over into Selena’s character. The scene where she discovers that her possible lover is also her enemy brings her two personae into conflict; the final line (especially as delivered by Michelle Pfeiffer) reflects her uncertainty as to how she should respond to this conflict.

This is not typical of the way humour is integrated into most action films. For an example of that, we need look no further than the first scene of Batman Forever, the first film in the series not directed by Tim Burton:

I suppose I couldn’t convince you to take along a sandwich.

I’ll get drive-thru. [6]

The point of the joke is straightforward enough: the image of a crime fighter stopping on his way to a battle evil-doers to pick up take-out food is absurd. However, the line is a throw-away; it isn’t tied to the story (which actually starts after this scene), and could be dropped without effect. By way of contrast, the joke from Batman Returns could not be removed without damaging the forward motion of the story.

In addition, the line violates what had been established as the character of the Batman in the previous films. Originally, he was a “Dark Knight” who had an internal struggle between his need to wreak vengeance on criminals (as a response to the murder of his parents by a petty thief) and his desire to retain his finer human sensibilities in the midst of the violence he has to deal with in Gotham City. He was a grim, largely humourless character.

The Batman has a number of one-liners throughout the film. While bantering with Dr. Chase Meridien, for instance, he says: “Are you trying to get under my cape?” and “It’s the car, isn’t it? Chicks really dig the car.” [7] Here, the humour arises out of the incongruity of a superhero using a cheap come-on line. However, once again, by using the identity of the character as the basis of a one-liner, the filmmakers undermine what we already know of the character. Bruce Wayne, being human, is the half of the character who is able to have relationships with women; Batman, being an inhuman avenging angel, is not capable of relationships with human women, and his double entendres here strike a seriously false note.

I’m not suggesting that a character cannot change over the course of a series of films; in fact, this is one way of maintaining an audience’s interest. However, such changes have to be credibly accounted for within the film in which they occur. Having a character change without a reason, as happens in Batman Forever, risks confusing an audience.

As portrayed in the third film, the Batman has moved closer to the traditional generic Hollywood action/adventure hero: quick with a joke, smooth with women and not afraid of the rough stuff. By blunting his interior struggle, the filmmakers have made him much less interesting, much more likely to be blown off the screen by the more colourful villians which are a large part of the appeal of films.

Giving an action hero humourous lines to deliver also risks alienating audience members by paradoxically making the character too dark. If the hero shoots a dozen bad guys and then tosses off a couple of one-liners, it appears as though he or she has a nihilistic attitude towards violence, something with which it is hard for an audience member to identify. [8]

In order to avoid this, many essentially serious action film heroes have a comic sidekick. In Star Wars, Luke Skywalker is a traditional hero, while the robots R2D2 and C3PO, although having one or two important story functions (such as when C3PO plays the message from Princess Leia for Luke, setting the story in motion), exist primarily as comic relief.

In any case, characters who throw off one-liners predominate in action films; the number of films in which the humour develops naturally from a combination of story and character is relatively small. There is a simple reason: one-liners are easy to write. If a producer feels an action script should be punched up with some humour, she or he can hire a gag writer for a week or two to come up with witty lines. Humour which arises out of character and situation, by way of contrast, is usually embedded within the structure of a film, and cannot, therefore, be written into a screenplay without affecting many of the scenes around it.

Unfortunately, this tends to reduce characters who should be substantially different to a single type. Consider three jokes from Batman Forever: after hitting somebody over the head with a coffee pot, one character says, “Caffeine’ll kill you.” [9] In another scene, a different character, complaining about his adversary’s ruthlessness, says, “He takes his job much too seriously!” [10] Finally, talking to a psychiatrist, a third character asks: “Wacko. Is that a technical term?” [11]

Which character said which line? [12] There’s no indication from the material itself, because all three characters use the same sort of sarcasm.

Contrast this to Batman Returns. When one character says, “I was their number one son, and they treated me like number two,” [13] you know it can only be the Penguin. The joke, being a crude [14] reference to excrement (which children refer to as “number two”), is perfectly in keeping with the Penguin’s character: having lived underground most of his life, he never learned the social graces. In addition, the joke is a reference to his past: his parents literally dumped him in a sewer.

Each of the major characters in Batman Returns has his or her own kind of humour. Bruce Wayne — as distinct from the humourless Batman — employs a gentle, self-deprecating irony. Selena Kyle’s ineptitude and mousiness are the initial humourous aspects of her personality. However, when she becomes Catwoman, her humour takes on an angrier (“Life’s a bitch — now so am I.” [15]), more sexual (to the first criminal she fights: “Be gentle, it’s my first time.” [16]) tone.

Putting It All Together

“Most generic movies depend on a cycle of tension and release for their impact. The classic American Western, such as Shane or High Noon, is a series of escalating violent incidents leading to a final, cleansing shootout. The monster movie and the haunted-house movie both work in cycles of tension, each attack another step toward the final confrontation between hero and creature.” [17]

As we have seen, humour can be effectively employed in an action/adventure film when it arises naturally out of character and situation. However, this still leaves us with the question of when humour should be injected into a script. Should it be used at random, or are there specific points at which it will be most effective?

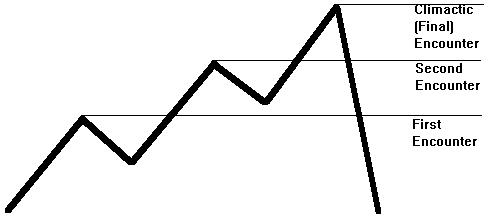

To answer this question, it is helpful to look at the form of a typical action screenplay. As director John Sayles put it, genre films require cycles of tension involving escalating action. For action films, there is a formula for determining such cycles: by the end of the first act, the hero must have had his first encounter with the villain or his subordinate (James Bond, for instance, will have sparred with, say, Oddjob); by the end of the second act, there must be a second encounter with higher stakes (Bond is nearly cut in two by a laser at Goldfinger’s hands); the third act will end with the climactic confrontation between hero and villain (Bond electrocutes Oddjob in Fort Knox and causes Goldfinger to be sucked out of an airplane window). This is a resilient formula which can be applied to a wide variety of action films (see Diagram One).

DIAGRAM ONE

The Escalating Action of a Typical Adventure Film

One important element of the action film formula is that some downtime after each encounter is necessary for the audience to catch its breath and prepare itself for the next bout of action. It is here that humour can be most effectively employed; not only will it not be competing with the action, but the release of endorphins at this point helps the audience catch its breath so that it can better appreciate the next cycle of tension.

To see how this works, let us return to Star Wars. Scenes where R2D2 flails helplessly as the Millenium Falcon is being chased or Luke infiltrates the Death Star are not effective as comedy, and tend to slow down the action. On the other hand, the character works as comic relief between action sequences (as in the robot auction or cantina scenes).

The “cat behind the door” is the classic formulation of this type of scene. Start with somebody in a room who is afraid that somebody else poses a threat to him or her. There is a sound in an adjacent room. Could it be the killer? The person walks across the room and opens the door to reveal…a cat which has knocked over a vase. At this point, the audience usually laughs with relief.

Then, of course, a shadow reveals that somebody, possibly the killer, has already entered the room, and a new escalation of tension begins.

Although often effective, this technique should be used with care. It is possible to create a series of scenes in which humour is logically employed in each, but the overall effect is to weaken the strength of the action. As with any screenplay, the parts must constantly be scrutinized to ensure that they properly contribute to the whole.

Conclusion

There are a couple of other ways of combining humour and action. The first involves the “thrill” comedy as practiced by such silent screen stars as Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton. In this kind of film, the audience is laughing even as the level of danger to the hero increases.

The best example of this kind of comedy is Llloyd’s Safety Last. The bulk of the film has Lloyd climbing up the side of a building to prove his love for a woman; on the way he has to contend with uncooperative birds, a rope thrown to him that isn’t tied to anything inside the building and a clock whose hand springs loose as he tries to negotiate it (the image of Lloyd dangling off the clock clutching to the skewed hour hand has become a film icon). As he gets higher and the adverse consequences of falling increase, the film gets funnier.

Safety Last uses the formula found in Chart One, alternating moments of suspense with moments of humour; however, rather than play it out over a single scene, the film employs the formula over most of its length. Imagine the chart extended upwards indefinitely. Llloyd does this using a single comic element: reversal of the audience’s expectations. After one thrilling scene, he scrambles to what he thinks is safety (say, by grabbing the rope), only to find that it isn’t safe at all. The audience’s first reaction to this unexpected twist is to laugh; but, inasmuch as the twist increases the danger to the hero, the ultimate result is increased tension. Until the next comic twist…

Buster Keaton used this technique most effectively in Our Hospitality. In it, Keaton’s character is reluctantly drawn into a feud with the male members of the family of a woman he has fallen in love with. In the climactic scene, Keaton, running away from the men who want to kill him, climbs down the face of a cliff to a cave. Unfortunately, getting down was easier than getting back up, and it seems he will be stuck there, until a friendly voice offers to drop a rope down and haul him up.

Unknown to Keaton, the person whose rope he ties himself to is one of the brothers out to shoot him. (The rope which looked like it was going to save him now could be his downfall.) The brother ties the rope to his own waist so Keaton cannot escape, then swings him over to another cave where he can get a clear shot at Keaton. But Keaton can now see him and, recognizing his enemy, pulls back to the wall of the cave just as he is about to be shot. This inadvertently pulls the man off the cliff. (The rope which was dangerous has now saved him.) Keaton sees the taut rope go slack, then a body falls past the cave, inevitably pulling him over the side. (The rope which saved him has now put him into new peril.) The two men fall into a river, where the alternating cycle of being in danger and being saved from danger (only to be put into a new form of danger) plays itself out in a dozen more creative ways.

Is “thrill” comedy really comedy? There is a legitimate comic device (reversal) involved in these films. It can be argued, though, that the humour arises more out of our relief that the character is safe, however fleeting that safety is; that our laughter is more an emotional response to what is happening to the character than a response to the humourous situation actually portrayed in the film.

Hey, whatever works.

Finally, there are rare films where the humour is developed in the midst of the action. In Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, for instance, where Uma Thurman’s character might die after accidentally snorting heroin. Her date’s panic, compounded by the panic of the drug dealer he takes her to in order to get help, is funny, especially when they start arguing about but we never lose sight of the fact that the woman’s life is at stake.

This scene has a number of features worth noting. The humour arises out of the exaggerated, inappropriate behaviour of the characters to a serious threat. In addition, the humour develops out of the action of the story and, although perhaps a bit over the top, is nonetheless consistent with what we know of the characters. Finally, the action itself, despite having deadly serious consequences, is the object of the humour.

Tarantino uses this strategy throughout Pulp Fiction. In the scene where Marsellus, a crime boss, is raped, boxer Butch, having decided to save him, goes up to a pawn shop to look for a weapon. He tries several increasingly brutal, increasing unlikely weapons, until he settles on a Samurai sword. The scene is funny because Willis’ nonchalent behaviour is at odds with the urgency of his goal; it also increases the tension of the sequence by momentarily putting off its resolution.

This is one of the reasons Tarantino’s dialogue, which many critics feel is often irrelevant to the story, actually plays an important role in the unfolding narrative. Early in Pulp Fiction, Jules and Vincent, two seedy hoods walk up to a door, guns drawn — they are obviously ready for some action. At the last moment, one of them decides it’s too early to go through the door, so they walk down the hallway and continue a conversation they were having about another hood who was probably beaten up for giving their boss’ wife a foot massage. The dialogue is amusing in itself, but, as they laugh at it, audience members are also wondering what’s going to happen when Vincent and Jules do finally enter the room.

Because action sequences often have life or death consequences, the sort of humor associated with them in this way is often considered grotesque. Many studios will not support films which use this technique because they fear (correctly) that it does not appeal to a lot of people, and will alienate too many potential audience members. It should also be noted that this kind of humour is a very delicate balancing act: too much exaggerated behaviour and you will dilute the tension of the scenes, which will no longer be believable; too little exaggerated behaviour and the humour will be overwhelmed by action.

One film in which this type of humour was effectively maintained throughout is Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, in which an insane Air Force General sends planes to use nuclear weapons against Russia, unaware that this will trigger a device which will destroy the world. You might get the impression that Strangelove is a serious suspense film (as, indeed, Failsafe, made the same year, was); however, the characters are so exaggerated that the effect is a very funny film. This mixture of absurd characters and serious situation (the stake in the film is all life on earth) works well on both levels.

Films like Dr. Strangelove or Pulp Fiction are rare examples of the delicate balancing act between action and humour actually working. Most often, humour, to be effective, should be used in the downtime between action sequences, developing naturally out of a combination of character and the forward motion of the story.

NOTES

1) For more on this subject, see: Ira Nayman, “Trends in Hollywood Screen Comedy,” in Creative Screenwriting, V2 N1 (Spring 1995).

2) Although the connection between laughter and the release of endorphins into the brain is well known, the reason for it is not. Some scientists theorize that laughing and grimacing long ago had the same purpose, and that socialization has given them different meanings. In any case, this phenomenon gives credence to anecdotal stories about seriously ill people who have gotten better after watching a lot of comic films and television shows.

3) For more on the nature of the fool, see: Enid Welsford, The Fool: His Social and Literary History [London: Faber and Faber, Ltd., 1935].

4) Sam Hamm, Batman Returns, August 1, 1991 draft, pages 97/98.

5) Since they contain the same sensibilities, I could have chosen either the first film in the series, Batman, or the second, Batman Returns as the basis for a comparison of how Tim Burton and another director develop humour through story and character. I have chosen the second film because, unlike most critics, I think it’s better than the first. In Batman, the plot is a series of encounters between Batman and the Joker, which gives it a certain predictability. Batman Returns, on the other hand, features three villains, each with clearly defined goals, whose alliances grow or wither as they see their self-interest changing. Structurally, the second film is far more interesting than the first.

6) Aviva Goldsman, Batman Forever, Production Draft, June 24, 1994, page 9. I was first introduced to this scene, as I suspect were most people, through the commercial for MacDonald’s in which it was featured several weeks before the film was released. I was astonished to see it actually in the film; I assumed it was extra footage shot specifically for the commercial. It has nothing to do with the story, and the film wouldn’t suffer if the short scene were removed. I suspect that the scene opening the film is a way for the producers to signal to the audience that it is going to be lighter than its predecessors, although, when I get especially cynical about the industry, I think the scene actually signals the ultimate commercialization of Batman as a film franchise.

7) ibid, page 49.

8) I am indebted to W. H. Park for this insight.

9) Goldsman, Batman Forever, 22.

10) ibid, 17.

11) ibid, 36.

12) The first line was uttered by Edward Nygma, the Riddler. The second was said by Two-Face. The final joke was made by Bruce Wayne.

13) Hamm, Batman Returns, 27.

14) Personally, I was shocked.

15) Hamm, Batman Returns, 54.

16) ibid, 43.

17) John Sayles, Thinking in Pictures: The Making of the Movie Matewan (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987), page 114.