People? Hello? Settle, people, settle. Lord knows, I have.

A couple of you actually managed to find me during my office hours. One is currently in the hospital being treated for pepper spray poisoning, the other has suffered some sort of “breakdown” and will probably require bed rest for the next several years. I did try to warn you about this last week – you really must pay attention.

In any case, their loss is your gain. One of them wanted to know why I don’t use Power Point presentations in my lectures. Well, I find that when students are attending to what’s happening on a screen, they tend not to give their full, rapt and undivided attention to what is the most important part of the lecture: ME! People, when I deign to go to academic conferences, undergraduate students genuflect when I pass and graduate students offer me their bodies in exchange for advising them. You think I have any intention of competing for your attention with coloured text and animated gifs?

I blame Sesame Street.

It’s already the second week of classes, and some of you are beginning to wonder what will be on the mid-term exam. Well, I like to think of myself as an intellectual sculptor, so, if you would like to know what you will be tested on, simply find yourself a copy of the latest edition of The Encyclopedia Britannica and carve away everything that is not related to semidiotics. Then, study your heart out.

Now that we have that taken care of, let us begin today’s lesson. You may be under the mistaken impression that words are primarily used by people to communicate ideas. I blame the public school system. In fact, there is a fundamental problem with words: people often object to the reality to which they refer. For this reason, words can just as often obscure reality as describe it.

Take the word “fire.” When we’re talking about the stuff Prometheus stole from the gods – the noun – we’re in pretty good shape. But, when we talk about throwing people out of their jobs – the verb – well! You wouldn’t believe the anger with which some people respond to the mere possibility of the mention of the word!

If you want to shed your company of workers, but don’t want to rile anybody up by using the word “fired,” you have to come up with another term, one less freighted with such negative connotations as hunger, lack of shelter and poor teeth. This is known as “finding a euphemism,” or, simply, “euphemizing.”

For a time, the word “fired” was successfully replaced by the term “laid off.” This sounded much softer: laying (down?) is so much better than being fired (out of a cannon?). Unfortunately, workers eventually came to realize that although the words may have changed, the reality had not: what was now being called a layoff was just a good old-fashioned firing, with all of the negative connotations of the original term.

Clearly, a new term was necessary. Initially, the term chosen to replace “layoff” was “downsize.” However, since the word “down” usually has negative connotations (as anybody who follows the stock market can attest), workers caught on pretty quickly. The term was replaced by “rightsize” which, rather than dragging the company down, made it perfect for the Middle Bear (ie: just right).

Now, people are beginning to find the term “rightsize” suspect; they are beginning to follow the chain of associated meanings back to fire. A term recently tested as a replacement for rightsize, “permanent involuntary leisuring,” holds great promise. After all, in this hectic world, who could possibly object to having more leisure?

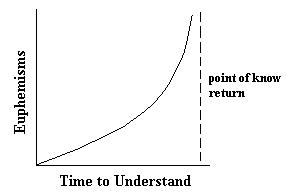

How long can a new euphemism survive before those who are supposed to be fooled by it catch on? We can get a sense of this by creating a graph with the number of terms used for a phenomenon on one axis and the time it takes for people to catch on to the term’s real meaning on the other axis. A generic example of such a “Euphemism Curve” is shown in Figure 1.

For those trying to soften or hide a harsh reality, it is necessary to stay ahead of the euphemism curve. That it to say, it is necessary to introduce a new euphemism just as people are starting to catch up to the one currently in use. Somebody who is skilled at staying ahead of the euphemism curve can keep a sizeable amount of the population in the dark for many years.

It is not possible to stay ahead of the curve forever, though. As you can see from Figure 1, the time between the introduction of a new euphemism and the point at which the public uncovers its ultimate meaning decreases the greater the number of euphemisms one employs. The curve eventually approaches the “Euphemism Curve Asymptote,” commonly referred to as the “point of know return.”

Figure 1

Generic Euphemism Curve

The asymptote is the point where the public understands euphemisms almost as soon as they are used, making their use moot. In the above example, at the point where the native population knows a lot of people are about to be fired, what management calls it becomes irrelevant; in fact, the closer you get to the asymptote, the more caution you must use in coining new terms, since the public will turn against you if it perceives that you are trying to pull the wool over its eyes.

I do not mean to imply, by my choice of example, that the euphemism curve applies only to business. Any institution that deals with the public will, from time to time, find it of use. The military, for example, has done well with the phrase “collateral damage” (oops, we accidentally broke something), which replaced the phrase “civilian casualties” (can’t get too worked up over something so casual), which had been used to describe the slaughter of innocent people in times of war. Why the military would not want to use the phrase “slaughter of innocent people in times of war” should be self-evident.

And, if you’re an average citizen who wants to understand what people are really talking about, well, a little common sense goes a long way: what do you think the Undersecretary of Public Diplomacy is in charge of?

To this point, we have looked at individual examples of euphemism degradation. What happens to a culture when euphemisms are liberally employed in every sector of life? Do we have a cultural point of know return? In a recent article in The Journal of Irreproducible Fungibility, Bausch and Lomb argue that the increased use of euphemisms over time creates a culture of disbelief. (They literally argue: Piotr Bausch and Herbert Lomb, brilliant researchers that they are, never did get along.)

Whether or not this is a bad thing depends upon what you think of individual participation in public life. If people become so cynical about the public pronouncements of business and political leaders that they stop believing anything these people say, they may be tempted to stop participating in public life. There is a possible downside, though: cynical citizens may become more active in the public sphere, questioning business leaders at shareholders meetings, for instance, or demanding public accountability from politicians. Such alarming behaviour is sometimes referred to as “public participation in democratic life.”

To forestall such dire consequences, most large organizations have staffs devoted to coining new euphemisms for public consumption. These are generally referred to as “public relations” departments. Public relations. In business, public relations used to be known as advertising; in government, public relations used to be known as propaganda. Who could object to the term? After all, every organization would like to foster a good relationship with the public.

However, as I stated, fostering good relations with the public appears to require telling it unpleasant truths in ways that appear to satisfy its need to know. Yes, this is very much like a dysfunctional marriage where nobody wants to admit that “staying late at the office” is actually a euphemism for “getting it on with the secretary” and “tired” is a euphemism for “drugged up to the eyeballs.”

That’s why I’m delighted to be single. But, that’s another matter.

You may wonder why businesses and governments don’t just tell the truth about what they’ve been up to. Obviously, you’ve never been married, either. The longer a couple is able to ignore dysfunction, the longer they can pretend that their marriage is mutually satisfying.

Okay. We just have enough time for one que – no, we don’t. Sorry. No, I’m not. But outright lying is a lecture for another time…