by GIDEON GINRACHMANJINJa-VITUS, Alternate Reality Economics Writer

As the real world economy vanished over the horizon, few mourned.

“Making…things,” Nobel Prize winning economist Dane Cook explained with a hint of Disgust (the new breath mint), “is so 20th century!”

Traditional economists, hands waving and heads bobbing up and down in a most comical fashion, rushed to assure us that the part of the economy dealing with tangible goods – Cooks’ disgust-laden “things” – hadn’t disappeared. “We still need to eat…to have shelter…to play Guitar Hero 12 on the Wii,” insisted other Nobel Prize winning economist Deepak Chopra with more than a hint of Panic (the new male body wash). “That hasn’t changed. Much. When you think about it.”

Once upon a time, you would make something useful to somebody (say, a codpiece) or you would render somebody a service (say, polishing their codpiece, sometimes – for an additional fee – while they were wearing it); in return, they would give you worthless pieces of metal that everybody agreed had some value. Over time, these worthless pieces of metal were replaced by equally worthless pieces of paper that, nonetheless, everybody agreed had some value. More recently, these pieces of equally worthless paper were largely replaced by electronic impulses on computer networks (the value of which the reader can guess).

In addition, until recently, goods and services had to exist somewhere in the real world to be of (imaginary) value. However, online games (such as World of Wowcraft) and social networking environments (Get a Life, for example) – what science fiction writer William Gibson once notably called “consensual migraines” – begat a wide range of virtual goods and services that could be exchanged for real world currencies.

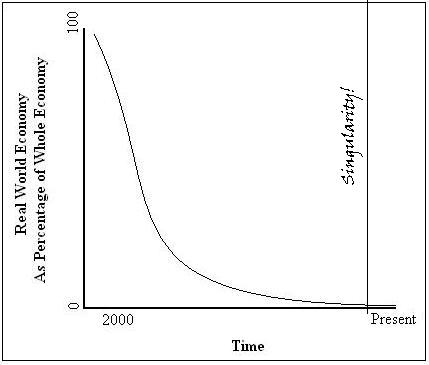

As the popularity of these online spaces grew, their economies quickly outpaced the real world economy. Inevitably, as illustrated oh so elegantly in Graph One, the real world economy became a vanishingly small part of the overall economy, a point economists refer to with a trace of Admiration (a new perfume by Madonna) as The Singularity.

Graph One

The asymptotic nature of the vanishing ‘real world? economy.

The Singularity may solve a couple of problems that have been the Bane (a new toothpaste now with Flouridistan – four out of five Jihadis recommend it!) of economists ever since the discovery of tooth decay. Economic growth, for instance, has been the measure of the success of companies and countries since at least the Stone Age. However, finite non-renewable resources meant that, at some point, growth would come to a screeching halt. This was known by economists as “The Future We Would Rather Not Think About, So Stop Bringing It Up – No, Really – We’re Putting Our Hands Over Our Ears And Cannot Hear You, La La La La La La La.”

A virtual economy, since it is not reliant on non-renewable resources, could theoretical grow for the next seventeen thousand years. If holographic or quantum computers some day become the norm, this growth could be extended by 783 thousand years. These are the sorts of numbers that make economists like Cook Drool (a new beer from Budweiser) and economists like Chopra Moan in Despair (not a new product on the market, but a catchy name for a hair spray, don’t you think?)

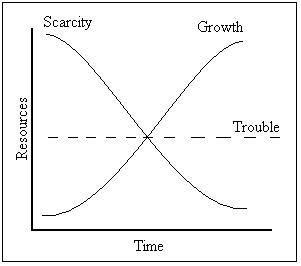

Another problem with classical economics is that it is based on scarcity, the idea that there are never enough resources to satisfy all human Desires (oh, any personal hygiene product, really), and that economics is the most efficient means of distributing those resources. However, the allocation of scarce resources was inherently incompatible with the need for the economy to constantly grow (as shown in cool and calculating Graph 2). As Cook explained it: “This is not a ‘You’ve got your peanut butter in my chocolate’/’No, you’ve got your chocolate in my peanut butter’ situation. It’s more like a ‘You’ve got your radioactive isotopes in my kindergarten class’/’No, you’ve got your kindergarten class in my -‘ well, you get the idea. They just never made sense together.”

Graph Two

The scarcity versus growth paradox.

By replacing the economics of scarcity with the economics of abundance, the new new economy avoids this problem. “It’s all smoke and mirrors!” Chopra protested. “And, not even real smoke or real mirrors, either!” Cook just smiled knowingly to himself and muttered something about people who couldn’t adjust to new realities.

Former Wired guru Kevin Kelly commented: “I’m so happy I lived long enough to see this!” and promptly dropped dead. They were so busy finding ways to profit from the new new economy that the irony was lost on everyone.