Decisions in a democracy are made badly when they are primarily made by and for the benefit of a few stake-holders (land-owners or content providers). (Boyle, 1997, unpaginated)

The thinking of government in the advanced industrial states remains by and large stuck in the worn-out groove of apportioning scarce resources, whether in terms of bandwidth allocation or licensing of content delivery. This defensive posture is inherently weak. The assertive approach would be to do everything possible to optimize the connectedness of the nation. This translates, first of all, into encouraging and supporting — financially, if need be — cable, telco, and even hydro joint ventures; second, combining these initiatives with educational programs that put the power of creation and idea development in the hands of the people, rather than exclusively under the control of established developers and information providers; third, maximizing access to copyright-free public domain material. (de Kerckhove, 1997, 175)

Carl Malamud: “Technology in itself is no guarantee of freedom of speech.” (Ginsburg, 1997, 131)

In these neo-Conservative times, it is politically fashionable to deride government as “the problem” and call for cutting it to the bone, privatizing as many of its functions as possible. Those who call for drastic cuts to government programmes forget that government is an instrument of the people, created to do our bidding. Far from being an enemy, government is a vital means by which the collective goals of a people, goals which they could not reach through their individual efforts, can be accomplished. If the people find a particular government is not acting in their interests, they can change its policies by putting pressure on it, or simply voting for a different government at the next election period; the answer is not to cut government back so severely that it cannot adequately maintain its many agreed upon worthwhile and/or necessary functions. Those who call for the privatization of most government functions forget a simple fact about markets: as we saw in Chapter Three, their purpose is the efficient allocation of resources. Period. Markets are not instruments through which socially just societies can be created; they have nothing to do with morality. Governments are the proper instruments for the exercise society’s moral will.

Governments have a number of tools which will, in one way or another, affect art and artists working in online digital media. One is legislation which attempts to directly control expression. Content control (which includes licensing regulations as well as outright censorship) is a stick used by governments to ensure that their nation’s culture is adequately portrayed in their media. Culture is a loaded term, and I don’t intend to get into a discussion of all its nuances here; what is important to note is that governments feel it necessary to promote their culture, however each specific government may define it. “[T]he primary regulatory objective is to protect and promote cultural values.” (Johnstone, Johnstone and Handa, 1995, 113) Some governments already feel that their cultures are under siege by American cultural products:

Will Western-produced news releases and films promote attitudes and opinions contrary to, and incompatible with, their own cultural values and national policies? Will reliance on other countries impede the development of indigenous skills for educational and entertainment programming? Will the lure of Western commercialism undermine their local consumer industries and entice the movement of scarce funds abroad? Will they become unwilling receptors of propaganda warfare between the superpowers and victims of internal interference by other nations? The essential issue is one of uncertainty over whose ideas and ideals will be promoted to which audiences and for what purposes. (Janelle, 1991, 78)

Many governments feel that this problem will be exacerbated by the growth of digital communication networks. “While international in scope, the Net has been dominated so far by American voices and sites.” (Kinney, 1996, 143)

Governmental control of content takes two general forms. Quotas which make radio and television licenses dependent upon the amount of regional programmes they carry are a form of positive control, in the sense that they require producer/distributors of works to act in a specific way. Laws against pornography or hate literature are forms of negative control, which require producer/distributors not to act in a specific way. This chapter will start with a discussion of negative control focusing on the American government’s Communications Decency Act. (You will recall that state censorship was mentioned as a drawback to publishing on the Web by respondents to my 1996 survey. Although not mentioned by respondents to the 1998 survey, it nonetheless has serious potential effects on their ability to use the Web as a publishing medium, and is, therefore, relevant to the current study.)

The nature of digital networks mitigates against government control in a number of ways, however: thus, we shall have to consider the possibility that the international, boundaryless nature of the Internet makes control by local governments unfeasible. This will make up the next section of the chapter.

One other area in which government may be seen to have a legitimate role is to negotiate the interests of various members of society, enforcing contracts between parties where necessary. Perhaps the most important example of this for creators is in the creation and enforcement of copyright law. As we saw in Chapter Two, some of the people who put their fiction on the World Wide Web are concerned with ensuring they get proper credit and, if possible, financial compensation for their work. The particular problems digital media create in regard to copyrights will be the subject of a section later in this chapter, where I shall argue that current developments in the law are to the detriment of individual content creators.

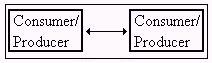

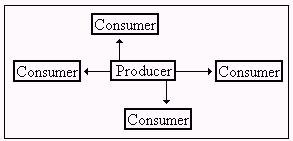

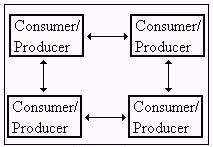

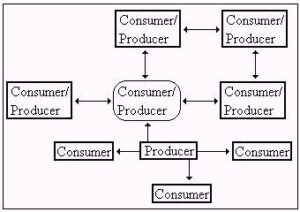

This will be followed by a discussion of a second major problem with any attempt by governments to regulate or otherwise control content on the Internet: the amorphous nature of digital media makes it unlike any existing medium. Three regulatory regimes have arisen to deal with existing media: broadcast, common carrier and First Amendment/free speech protection. Each regime creates different opportunities for positive control of a medium. Perhaps more important for our purposes, each regime favours different stakeholders in the medium; using one model will foreclose the possibility of people using the medium based on another model. A fourth model will be introduced which will bypass the shortcomings of attempts to understand the Internet using existing models, a model which will suggest that new thinking is required by governments intent on any form of regulating this new medium.

Although many hoped to make money from their Web publishing efforts, none of the writers and only one publisher mentioned state support as a source. Nonetheless, many governments (including that of the United States) directly subsidize the work of artists through economic loan and grant programmes. For this reason, the chapter, which began with the stick of government regulation, ends with the carrot of government support. The purpose of government subsidization is to support the creation of worthwhile works of art which would not otherwise be supported by the marketplace. Such works are sometimes attacked for their lack of commercial viability, but those who do so forget that that is part of the rationale of public support in the first place: if such works were commercially viable, they would not need government support. Inasmuch as society benefits from the widest range of works of art, if the marketplace will not support the creation of certain types of work, some other mechanism must be found. In the final section of this chapter, I will look at a few of the programmes in Canada which are intended to financially support the creation of digital artworks.

The Stick: Government Control Through Censorship

Government control over communication media is not new, of course.

Every communications advance in history has been seen by self-appointed moral guardians as something to be controlled and regulated. By 1558, a century after the invention of the printing press, a Papal index barred the works of more than 500 authors. In 1915, the same year that the D. W. Griffith film ‘Birth of a Nation’ changed the U.S. cultural landscape, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of an Ohio state censorship board created two years earlier, thus exempting motion pictures from free speech protection on the grounds that their exhibition ‘is a business, pure and simple, originated and conducted for profit….’ (Human Rights Watch, 1996, unpaginated)

Many literary works which are now considered classics (everything from Women in Love to Huckleberry Finn) were banned from some jurisdictions because of their content (and the Papal index of forbidden works still exists and is regularly updated). Freedom for adults to read or view material intended specifically for adults was hard won. However, there seems to be a widespread unspoken assumption that electronic forms of speech should not enjoy the same protections that the printed and spoken word do.

This seems to be the reasoning behind the ill-fated 1995 American Communications Decency Act. As an exemplar of the government tendency to attempt to control the media, this is a good place to start an investigation of state censorship.

The Communications Decency Act

Everybody has a favourite cause these days. Mine is smut. I’m for it. Now, owing to the way the laws are written…this is a free speech issue. But we know what’s really going on here. Dirty books are fun. (Lehrer, 1965)

In 1994, Senator James Exon, a Democrat from Nebraska, introduced the Communications Decency Act (CDA) in the United States Senate. Congress stopped sitting before the Senate had time to consider Exon’s bill, so it quietly died. However, Exon reintroduced the bill in the next sitting of the Senate the following year.

The CDA amended the Communications Act of 1934 in order to accomplish two goals. The first was to make it a crime to use computer networks in order to harass another person. According to Exon, “Under my bill, those who use a telecommunications device such as a computer to make, transmit or otherwise make available obscene, lewd, indecent, filthy or harassing communications could be liable for a fine or imprisonment. That is the same language that covers use of the telephone in such a manner.” (undated, unpaginated)

The second goal of the CDA was to protect minors from coming across sexually explicit content online. The CDA made it a crime for anybody who “knowingly within the United States or in foreign communications with the United States by means of telecommunications device makes or makes available any indecent comment, request, suggestion, proposal, image to any person under 18 years of age regardless of whether the maker of such communication placed the call or initiated the communication…” (S.314, 1995, 47 U.S.C. 223 (e)(1)) Anybody violating the Act would be liable for a fine of up to $100,000 and a maximum sentence of two years imprisonment. (ibid)

Proponents of the CDA argued that it was an extension of existing protections for minors into the online world. For example, Cathleen A. Cleaver, director of legal studies at the Family Research Council, stated that “We have long embraced laws that protect children from exploitation by adults. We prohibit adults from selling porn magazines or renting X-rated videos to children. We also require adult bookstores to distance themselves from schools and playgrounds. Do these laws limit adults’ freedom? Of course they do. Are they reasonable and necessary anyway? Few would dispute it.” (1995, unpaginated) Exon himself claimed that “We based this on the law that has been in effect and been approved constitutional with regard to pornography on the telephones and pornography in the U.S. mail. We’re not out in no-man’s land. We’re running on the record of courts’ decisions that have said you can use community standards to protect especially kids on telephones and in the mails. We’re trying to expand that as best we can to the Internet.” (“Focus — Sex in Cyberspace,” 1995, unpaginated)

Cleaver used an interesting analogy to support her position: “[W]e know that pedophiles traditionally stalk kids in playgrounds. Well, we know that computers are the child’s playground of the 1990s. That is where children play these days increasingly. So it is a really toxic mix to have these playgrounds be a place where children are fair game to pedophiles. It is very disturbing.” (McPhee, 1996, unpaginated) Declan McCullogh, a free speech advocate who posted this to the Web, was sarcastic about Cleaver’s position. To be sure, the suggestion that children are fair game to pedophiles on the Net is inflammatory rather than enlightening.

However, Cleaver’s analogy should not be dismissed out of hand. Where new technologies are introduced into a society, many people’s initial reaction is to compare them with existing technologies; this makes understanding and accepting them easier for a lot of people. Above, Exon claimed that the CDA was drawn on existing laws governing the telephone and the mail, making an explicit analogy between those media and the Internet. Cleaver compared pornography on the Internet to that found in adult bookstores. As we shall see, opponents of the CDA make different comparisons; in fact, the battle over the CDA can be seen, in part, as a duel between analogies for the Internet. (This may be true of differences of opinion on the nature of the Internet more generally.) Moreover, spatial metaphors abound on the Internet: for instance, Blithe House Quarterly, one of the ezines explored in Chapter Two, has a picture of the floor plan of a building on its contents page, with each story assigned to a room. Because the two phenomena being compared in any analogy are not identical, an analogy necessarily distorts the nature of what is being discussed. Some analogies, in fact, conceal more than they reveal. The test of a good analogy is how closely related the two phenomena being compared are, and how great the differences between them are. Given all of this, there was (and is) merit in the analogy of places children go online to playgrounds in the real world, and those who opposed the legislation to control pornography on the Internet would need to address this issue.

It is also important to note, before we visit the controversy that the law created, that proponents of the CDA were not necessarily raving anti-free speech zealots, as they were sometimes portrayed by anti-CDA activists. There is a broad consensus in North American society that minors should not be exposed to sexually explicit pictures or stories. While there may be debate about the line at which the definition of minors should be drawn (are 16 or 17 year-olds knowledgeable enough to experience sexually explicit materials without harm?), it is generally accepted that pre-pubescent children are not yet sufficiently emotionally mature to deal with sexually mature subjects. With few exceptions, opponents of the CDA ceded this point. Thus, the CDA was an attempt to create a law which would accomplish a largely accepted social good; the only controversy was whether it was the best means to accomplish this goal.

The CDA passed the Senate by a vote of 84 to 16 on July 14, 1995. (Corcoran, unpaginated) “On June 30, 1995, Representatives Cox and Wyden introduced the Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act as an alternative to both the CDA and the Leahy study. The Act would prohibit content and financial regulation of computer based information service by the FCC. In addition, it eliminates any liability for subscribers, service providers or software developers who make a ‘good faith’ effort to restrict access to potentially ‘objectionable’ content.” (Evans and Stone, 1995, unpaginated) This Act was overwhelmingly passed by the House of Representatives. Negotiations between representatives of the two houses resulted in acceptance of Exon’s version of the bill. The CDA was attached to the Telecommunications Act of1996; it was just a small part of a law whose major purpose was to change the telecommunications industry, allowing, for example, local and long distance telephone carriers to compete in each other’s jurisdictions. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 was signed by President Bill Clinton on February 8.

The passage of the CDA in Congress had little effect online. “[D]espite the new law, for the most part it was business as usual on the net, where a search under ‘XXX’ or ‘sex pictures’ produced quick cross-references to dozens of sites promising a variety of products and services.” (Reuters, 1995, unpaginated) Even the passage of the Telecommunications Act, which included the CDA, didn’t affect what was available online: “Pornographic sites still offer up obscene pictures and stories of incest and rape still wait to be read on the Internet bulletin board Usenet, where a new group was formed Thursday night — alt.(expletive).the.communications.decency.act.” (Associated Press, 1995, unpaginated)

While the Internet community didn’t visibly change its online behaviour because of the Telecommunications Bill, reaction to the bill offline was immediate. Minutes after Clinton signed the bill, “the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed suit challenging the law’s constitutionality. The CDA was on the books for one week and then was restrained by District Judge Ronald Buckwalter.” (“Communication Decency Act,” 1997, unpaginated) Nineteen groups joined the suit, which was presided over by a panel of three judges in Philadelphia, including: the National Writers Union, the Journalism Education Association, Planned Parenthood Federation of America and Human Rights Watch. (Associated Press, 1996, unpaginated)

A second challenge to the Act was undertaken at the same time. On the day that the Telecommunications Act was signed, an inflammatory editorial was published in an online newspaper called The American Reporter. It read, in part, “But if I called you [Congress] a bunch of goddam motherfucking cocksucking cunt-eating blue-balled bastards with the morals of muggers and the intelligence of pond scum, that would be nothing compared to this indictment, to wit: you have sold the First Amendment, your birthright and that of your children. The Founders turn in their graves. You have spit on the grave of every warrior who fought under the Stars and Stripes.” (Russell, 1996, unpaginated) Strong stuff, not typical of The American Reporter. However, as the editor put it in an editorial published in the same issue, “This morning, we are publishing as our lead article a startling piece of commentary by a brave Texas judge, Steve Russell, who is risking his position and his stature in the community to join us in a fight against the erosion of the First Amendment.” (Shea, 1996, unpaginated) An attorney for the publication filed for an injunction against the CDA in New York, where a second panel of three judges was asked to rule on it.

At the same time as these suits were pursued, a variety of protests against the CDA were organized to raise public awareness of the problems some people and groups had with it. Protesters included the Community Breast Health Project, Surf Watch, Sonoma State University, the Abortion Rights Activist Page, Internet on Ramp, authors, computer programmers and graphics designers. (Associated Press, 1996, unpaginated) As their one form of online protest, many sites on the World Wide Web (mostly, but not exclusively, pornographic) turned their background to black and added links to Web pages containing arguments against the CDA. Some suggested that this latter action mostly preached to the converted, to little effect: “This collective act of protest was greeted, at best, with a yawn in Washington and, at worst, with a collective ‘Who cares if their web pages are black? The fools.'” (O’Donnell, 1996, unpaginated) However, the protests seemed to galvanize the online community, giving its offline protests more coherence and weight.

Those opposed to the CDA argued against it on a variety of grounds. The CDA outlawed the transmission of obscene material over the Internet. “The First Amendment protects sexually explicit material from government interference until it is defined as obscene under the Supreme Court’s guidelines for analysis in Miller v. California… Once characterized as obscenity, such material has no First Amendment protection. None of the Communications Decency Act prohibitions of obscene materials violates the First Amendment.” [note omitted] (Evans and Stone, 1995, unpaginated) However, since obscene material was already illegal, the CDA was unnecessary. In a similar vein, “The Supreme Court has also held that child pornography is not protected by the First Amendment. In New York v. Ferber, the Court relied on the fact that child pornography is created by the exploitation of children, and that allowing traffic in child pornography provides economic incentive for such exploitation. The Court also found that such material possesses minimal value. Therefore, child pornography lies outside the protection of the First Amendment and can be prohibited.” (ibid) New laws in this area are only necessary when new media have aspects which make the applicability of existing laws unclear; in such cases, all the new law has to do it clarify how existing law will be applied to the new medium. Since the obscenity and child pornography rulings were not specific to a given medium of communications, they could be applied to the Internet, making the parts of the CDA which covered those issues redundant.

However, the CDA went much further, banning “lewd, indecent, filthy or harassing communications.” According to many critics, this was a completely different kettle of fish. “What is ‘indecent’ speech and what is its significance? In general, ‘indecent’ speech is nonobscene material that deals explicitly with sex or that uses profane language. The Supreme Court has repeatedly stated that such ‘indecency’ is Constitutionally protected. Further, the Court has stated that indecent speech cannot be banned altogether — not even in broadcasting, the single communications medium in which the federal government traditionally has held broad powers of content control.” (Electronic Frontier Foundation, undated (a), unpaginated)

Anti-CDA activists claimed that changing the definition of unallowable material from obscene, which was not Constitutionally protected, to indecent, which to that point had been, would have a chilling effect on speech online. The legal test for obscenity involves three qualifications, the final one being that the work in question “taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” (Evans and Stone, 1995, unpaginated) Thus, even if it has explicit sexual content, everything from a respected novel to an academic paper cannot be considered obscene. However, because the legal test for indecency does not have this provision, those same works can be considered indecent. “Any discussion of Shakespeare or safe sex would not be allowable except in private areas, where someone can be paid for the task of rigidly screening participants.” (Oram, et al, 1995, unpaginated) Other examples of indecency “could include passages from John Updike or Erica Jong novels, certain rock lyrics, and Dr. Ruth Westheimer’s sexual-advice column.” (Electronic Frontier Foundation (a), unpaginated) Moreover, “As Human Rights Watch, a member group of the coalition [against the CDA], argued in an affidavit to the Supreme Court, the law’s prohibition of ‘indecent’ speech could be applied to its own human rights reporting that includes graphic accounts of rape and other forms of sexual abuse.” (Human Rights Watch, 1999, 31)

The legality of one Web page devoted to its creators favourite paintings came under question:

As nearly as I can tell, most of [the paintings] would qualify as being indecent under the Communication Decency Act. Were the Communication Decency Act to be broadly enforced, it would be illegal to maintain these images on a server located in the United States… Most of the pictures at this page are pre-Raphaelite — either painted by members of the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood itself, or by artists with similar inspirations. While it’s beyond the scope of this page to get into a detailed discussion of pre-Raphaelite art, I find it particularly significant that in their day, many of the pre-Raphaelite artists were decried as “indecent,” perhaps by people with the same narrow mindset as our contemporary politicians and law-makers. (Rimmer, 2000, unpaginated)

Perhaps most immediately relevant for our purposes is the fact that, as we saw, some of the stories written by the writers surveyed in Chapter Two and posted to the Web contained graphic descriptions of sexual acts or profane language. These stories would likely have been considered indecent and made illegal under the CDA. In Chapter Two, I tried to show how the graphic passages were not merely prurient, but part of the overall artistic intent of the writers. While this would be a defense against charges of obscenity in print, it was not a defense against charges of indecency under the CDA. Thus, many of the writers in the survey (the majority of whom, you will recall, were Americans) would have had to remove their work from the Internet or faced criminal charges. It is also worth noting that, in quoting passages from such work, this dissertation would have been illegal under the CDA. While I am a Canadian, and the dissertation will be published on a server in Canada, if it were mirrored on a server in the US, the ISP would likely have been liable under the CDA.

If widely enforced, the CDA would have the effect of limiting communication on the Internet to what would be acceptable for children. In doing so, the Act essentially criminalized speech on the Internet which would be acceptable in other media. For example, The American Reporter editorial quoted above was written specifically to test the limits of the CDA; the author and publisher assumed it was illegal under the Act. However, “Recently, the editorial, shortened for space but with the same raw language, was reprinted in the May issue of Harper’s magazine. There is no possibility, however, that Harper’s publisher could face criminal sanction for distributing the commentary in print.” (Mendels, 1996, unpaginated) Analogies between online communication and existing communications forms abounded: “It’s as if the manager of a Barnes & Noble outlet could be sent to jail simply because children could wander the bookstore’s aisles and search for the racy passages in a Judith Krantz or Harold Robbins novel.” (Electronic Frontier Foundation, undated (a), unpaginated)

The National Writers Union summed up this argument when it resolved that “Electronic communication should have no less protection than print or any other form of speech.” (1995, unpaginated)

Another important objection to the CDA was that it cast its net too wide. Defending the Act, former Attorney-General Edwin Meese, et al argued that

It is not possible to make anything more than a dent in the serious problem of computer pornography if Congress is willing to hold liable only those who place such material on the Internet while at the same time giving legal exemptions or defenses to service or access providers who profit from and are instrumental to the distribution of such material. The Justice Department normally targest [sic] the major offenders of laws. In obscenity cases prosecuted to date, it has targeted large companies which have been responsible for the nationwide distribution of obscenity and who have made large profits by violating federal laws. (1995, unpaginated)

The CDA could be interpreted to hold Internet Service Providers (ISPs) liable for the content on their servers. There are many reasons to object to this. The first is that most ISPs do not screen content; it flows through them. Owing to the nature of the medium, ISPs could be prosecuted for material which they couldn’t possibly know was going through their systems. As Mike Godwin stated, “Internet nodes and the systems that connect to them, for example, may carry [prohibited] images unwittingly, either through unencoded mail or through uninspected Usenet newsgroups. The store-and-forward nature of message distribution on these systems means that such traffic may exist on a system at some point in time even though it did not originate there, and even though it won’t ultimately end up there.” (Evans and Stone, 1995, unpaginated)

The CDA would seem to require ISPs to substantially change the nature of their business. Some commentators argued that this could have a potentially devastating effect on the industry:

The CDA as passed by the Senate would put the burden of censorship directly on the service providers. Under this burden, the risk of litigation would literally put a vast number of service providers out of business. The result of which would be fewer service providers who will then charge higher access fees based on the shrinking ‘supply’ of access to these services. Service providers will also be required to ‘insure’ themselves from the potential litigation. In addition, the service providers will be required to invest in new technology to ‘censor’ the content provided to their subscribers as well as the information passing through their systems. There is no doubt that these costs will be passed along to individual subscribers by the service providers. (ibid, unpaginated)

It was also argued that the volume of traffic which passes through the Internet would make it impossible for any ISP to properly monitor. We shall come back to this point later in the chapter.

Finally, it was pointed out that there were alternatives to government censorship of the Internet. One technical method for keeping minors away from adult content was known as filters. A typical filtering program, Surfwatch, “uses multiple approachs [sic], including keyword- and pattern matching algorithms; the company uses its blocked site list as a supplement to its core filtering technologies… ” (Godwin and Abelson, 1996, unpaginated) Most of the major commercial ISPs offered their own software for concerned parents:

Compuserve offers a kids’ version of WOW!, which lets parents screen their kids’ incoming e-mail, has no chat or shopping features, and restricts Web access to sites approved by WOW!’s staff. America Online provides filters that allow parents to restrict children to Kids Only areas that are supervised by adults, allows parents to block all chat rooms, selected chat rooms, instant messages (a sort of instant e-mail), and newsgroups. Prodigy lets users restrict children by limiting access to certain newsgroups, chat rooms, and the Web. Yahooligans! will permit access only to Internet areas rated “safe.” Microsoft Network’s service automatically restricts access to adult areas except to users who have submitted an electronic form requesting access; Microsoft then checks to see if the account is subscribed to someone over 18. [notes omitted] (Bernstein, 1996, unpaginated)

Legal precedent for American government regulation of speech requires “what the judiciary calls the ‘least restrictive means’ test for speech regulation.” (Electronic Frontier Foundation, undated (b), unpaginated) This means that, if there is a means of accomplishing the aim of government regulation without actually having the government put controls on speech, that means is preferable. Opponents of the CDA argued that, while imperfect, the Internet offered a variety of tools which parents could use to protect their children from indecent materials; if used, filtering mechanisms would protect minors without affecting speech which was legal for adults. [1]

The courts found the anti-CDA arguments compelling: “…on June 11, 1996, a panel convened in Philadelphia, consisting of Chief Judge Dolores Sloviter and Judges Ronald Buckwalter and Stewart Dalzell, enjoined the enforcement of the CDA, finding the statute to be unconstitutional on its face. On June 13, 1996, a panel convened in New York, consisting of Chief Judge Jose Cabranes and Judges Leonard Sand and Denise Cote, entered a similar injunction.” [notes omitted] (Bernstein, 1996, unpaginated)

The government appealed the ruling of the Philadelphia court to the Supreme Court. On June 26, 1997, in the case of Reno vs. the American Civil Liberties Union, the Supreme Court found that the “CDA’s indecent transmission’ and ‘patently offensive display’ provisions abridge the freedom of speech’ protected by the First Amendment.” (Wisenberg, 1997, unpaginated) The Court largely agreed with the reasoning of those who opposed the CDA. On the issue of indecency, for instance, the Court stated that “Although the Government has an interest in protecting children from potentially harmful materials…the CDA pursues that interest by suppressing a large amount of speech that adults have a constitutional right to send and receive…” (ibid) On the issue of filters, the Court stated that “The CDA’s burden on adult speech is unacceptable if less restrictive alternatives would be at least as effective in achieving the Act’s legitimate purposes… The Government has not proved otherwise.” (ibid) [2]

Thus, by a margin of 7-2, the Supreme Court struck down the Communications Decency Act.

During its lifetime, debate about the CDA was highly polarized and quite vituperative. Judge Russell’s profane article in The American Reporter was not the only provocation. Online journalist Brock Meeks, writing for HotWired, claimed that retaining the indecency standard “is akin to ramming a hot poker up the ass of the Internet.” (1995, unpaginated) Another commentator called the CDA “…Exon’s pillaging of freedoms in the online world.” (Corcoran, unpaginated) Still another opponent of the bill posted the following to the Net:

The [German] purity crusade now found a focus in the “Act for the Protection of Youth Against Trashy and Smutty Literature,” a national censorship bill proposed to the Reichstag late in 1926. This Schmutz und Schund (Smut and Trash) bill, as it was dubbed, aroused fears in German literary and intellectual circles, but the Minister of the Interior soothed the apprehensive with assurances that it “threatens in no way the freedom of literature, [the] arts, or [the] sciences,” having been designed solely for the “protection of the younger generations.”

It was aimed only at works which “undermine culture” and purvey “moral dirt,” he added, and had been devised “not by reactionaries, but by men holding liberal views…” On December 18, 1926, after a bitter debate, the Schmutz und Schund bill passed the Reichstag by a large majority. (Boyer, unpaginated)

The intention, of course, was to compare proponents of the CDA to those who paved the way for Nazi Germany. [3]

But what actually happened here? Congress enacted a law which would have curbed certain kinds of speech. The Supreme Court found it unconstitutional and struck it down. It is unreasonable to expect that every law Congress will pass will be perfect; it is an imperfect institution populated by flawed human beings. That’s why there are three branches to government in the United States: they are meant to be a check each other’s excesses. It seems to me that, tested though it was, the system worked: a bad law was not allowed to stand. Those who were most uncivil in their discussions of the CDA showed a lack of faith in the checks and balances which are supposed to be the great strength of the American system.

After the CDA

The Supreme Court striking down the Communications Decency Act did not end American government efforts to control the content of digital communications networks in the name of protecting children. In the House of Representatives, the Internet Freedom and Child Protection Act of 1997 was introduced in order “To amend the Communications Act of 1934 to restore freedom of speech to the Internet and to protect children from unsuitable online material.” (HR 774 IH, unpaginated) By combining “Internet freedom” with “child protection,” supporters of this bill hoped to make it clear that their efforts to keep material out of the hands of children would not interfere with the rights of adults to engage in protected speech (an important lesson of the defeat of the CDA). This bill added an interesting twist to the debate by mandating that “An Internet access provider shall, at the time of entering an agreement with a customer for the provision of Internet access services, offer such customer, either for a fee or at no charge, screening software that is designed to permit the customer to limit access to material that is unsuitable for children.” (ibid)

In addition, individual states have the ability to pass their own content control laws. “Legislation restricting speech on computer networks has been signed into law in Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Montana, Oklahoma, and Virginia; and additional legislation is pending and will very likely be signed into law in Alabama, California, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington.” (National Writers Union, 1995, unpaginated) At the time the CDA was being debated, the American Civil Liberties Union claimed to be monitoring bills being proposed in 13 states. (undated, unpaginated)

Moreover, the protection of children is not the only rationale behind legislative attempts to control the content of the Internet. One bill would have made it illegal to transmit information about the making of bombs (the bill, S. 735, and commentary on the bill (Center for Democracy and Technology, 1995) can be found on the Web). There have also been attempts to revive the Comstock Act, first enacted in 1873, which made it illegal to discuss any aspect of abortion, in order to outlaw speech on abortion on the Internet. (Schroeder, 1996, unpaginated) Since they were both efforts to ban speech which was protected by the First Amendment, and which could readily be found in other media, these laws would likely have not survived a court challenge had they been enacted.

Censorship in the Rest of the World

American government attempts to control online speech are noteworthy because of the fact that the United States has a long history of supporting freedom of speech, and the country frequently holds itself up as a model for the rest of the world. However, there are many countries in which attempts at government control over digital communications networks are much more repressive than those in the United States. This section, which is not meant to be comprehensive, will look at some of the attempts to control speech on the Internet around the world.

In 1996, German authorities asked CompuServe, an international Internet Service Provider, to stop carrying 200 newsgroups which public prosecutors in that country had deemed illegal; the company complied. Unfortunately, “Since CompuServe’s software did not initially make it possible to differentiate between German subscribers and others for access to newsgroups, CompuServe suspended access to a number of newsgroups to all its subscribers world-wide…” (European Union Action, 1999, unpaginated) While the prosecutors claimed to be targeting pornography, the effect of their action was to stop CompuServe clients from accessing information on a wide variety of subjects. According to Anna Eshoo, who was, at the time, a Democratic Senator from California, “Among the items that CompuServe is being forced to hide from its four million users are serious discussions about Internet censorship legislation pending in Congress, thoughtful postings about human rights and marriage, and a support group for gay and lesbian youth.” (1996, unpaginated)

This effort was doomed for a variety of reasons. CompuServe clients outside Germany complained that they were no longer getting newsgroups which were perfectly legal in their countries. Moreover, “CompuServe users still of course had access to the Internet and could therefore connect to other host computers that carried the forbidden newsgroups.” (Human Rights Watch, 1996, unpaginated) Eventually, CompuServe improved its software such that it could keep specific newsgroups from the citizens of specific countries, and only blocked Germans from accessing the newsgroups the German prosecutors had asked to be blocked. For their part, the prosecutors relented and allowed all but five of the newsgroups to be reinstated.

You might assume that the lesson to be learned from this experience was that governments didn’t have as much power to control content on the Internet as they might like. In fact, representatives of the European Union, meeting in order to discuss how it should approach Internet regulation, came to a different conclusion: “This demonstrates that there is a need for co-operation between the authorities and Internet access providers in order to ensure that measures are effective and do not exceed what is required.” (European Union Action, 1999, unpaginated) As we have seen, many involved in the battle over the CDA argued that ISPs could not, for moral and practical reasons, be held responsible for the content on their servers which had been created by others. A discussion paper by and for members of the European Union suggests otherwise:

Because of the way in which Internet messages can be re-routed, control can really only occur at the entry and exit points to the Network (the server through which the user gains access or on the terminal used to read or download the information and the server on which the document is published)… [Therefore, if] the illegal content cannot be removed from the host server, for instance because the server is situated in a country where the authorities are not willing to co-operate, or because the content is not illegal in that country, an alternative might be to block access at the level of access providers. (ibid)

Nor are they alone. Singapore, for example, treats the Internet like a broadcast medium, licensing service providers on the condition that they do not carry material unacceptable to the government. (Human Rights Watch, 1996, unpaginated) In South Korea, “Local computer networks will be asked to prohibit access by local subscribers to banned sites, according to the Information and Communications Ethics Committee of the Data and Communications Ministry.” (ibid) As Human Rights Watch points out, “Censorship efforts in the U.S. and Germany lend support to those in China, Singapore, and Iran…” (ibid)

Many governments use technical means to try and control what information their citizens can access. “Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and the United Arab Emirates impose censorship via proxy servers, devices that are interposed between the end-user and the Internet in order to filter and block specified content.” (Human Rights Watch, 1999, 1) To get around this, citizens of these countries can dial into servers in other countries which do not filter communications. However, international phone rates in these countries can be high enough to ensure that only the richest citizens will be able to pursue that option.

Some countries have extended existing laws to the online world. For example, “Internet regulations in Tunisia explicitly extend criminal penalties for defamation and false information to online speech.” (ibid, 3) Other countries, while they have not developed laws or regulations specific to the Internet, apply existing laws to it: ” Jordan and Morocco…” for instance, “have laws that curb press freedom and those laws, such as the ones that prohibit defaming or disparaging the monarchy, narrow the boundaries of what can be expressed online.” (ibid) Finally, as this last example suggests, some countries attempt to control content on the Internet which is specifically political: “The governments of Tunisia, Bahrain, Iran and the United Arab Emirates are among those that block selected Web sites dealing with politics or human rights, thus preventing users in their respective countries from accessing them.” (ibid, 4)

Attempts by governments to censor material on the Internet have two effects on writers. As we saw in Chapter Two, the number of writers from countries other than the United States was underrepresented in my survey. A contributing factor to this may be that stricter censorship laws in other countries inhibits the posting of certain kinds of information. The other effect is that, despite the feeling that some writers have that publishing online makes everybody connected to the Internet in the world their potential readership, the actual readership for their stories is much smaller for reasons that have nothing to do with the technical aspects of the medium and everything to do with politics.

Dirty books today

Are bold and getting bolder

For smut, I’m glad to say,

Is in the mind of the beholder

When correctly viewed

Everything is lewd

I could tell your stories about Peter Pan

And the Wizard of Oz? There’s a dirty old man! (Lehrer, 1965)

As we saw at the beginning of the chapter, governments will always try to control new media. Sometimes, enlightened legislators will pull back from such efforts; at other times, enlightened courts will strike down such efforts. With regard to the Internet, it has been argued that the international reach of the medium itself makes local and national government regulation difficult, if not impossible. During the battle over the Communications Decency Act in the US, for instance, Jerry Berman of the Center for Democracy and Technology argued, “I don’t know where Sen. Exon downloaded the materials that he found abhorrent, but if they’re downloaded from Sweden or they’re downloaded from Denmark, which looks exactly like any U.S. site, any law that he passes will not reach it.” (“Focus — Sex in Cyberspace,” 1995, unpaginated) Even a pro-CDA representative had to admit that, “the internet is global. How could we regulate pornography when foreign countries are producing 30% of it?” (The person went on to answer his own question: “Well, America has always been the policeman of the world. It has many foreign policies tools to enforce such a law.” (Gensler, 1997, unpaginated)) Setting aside the question of whether or not the United States has the right to enforce its morality on other nations, Gensler acknowledges an important point: how does an international communications system such as the Internet affect the ability of nation-states to control what information their citizens can access? This is the subject of the next section.

Problems with Government Regulation 1: Jurisdictional Disputes

In 1993, Paul Bernardo was charged with the sexual abuse and murder of Kristen French and Leslie Mahaffy. His accomplice, Karla Homolka, cut a deal with the Crown: in exchange for a reduced sentence, she agreed to testify against Bernardo. In a case of really bad planning, Bernardo’s trial did not take place until over a year and a half after Homolka’s. Realizing that if the details of the Homolka trial were made public, the jury pool for the Bernardo trial could be poisoned, Mr. Justice Francis Kovacs of the Ontario Court’s General Division placed a ban on the publication in Canada of any of the details revealed in the Homolka trial. The ban was to last until the Bernardo trial.

At the time, I was learning about computer mediated communications networks, particularly the Internet. I had heard rumours that details of the Homolka trial could be found there. Curious about this possibility, I used Archie and anonymous ftp (the World Wide Web had yet to be given its convenient graphical interface) and found an American newspaper report of the trial in a computer at the University of Buffalo. The whole procedure took me approximately 30 seconds. (I had no interest in the trial itself, so I gave the file to a friend, who was outraged enough for the both of us.)

The belief at the time was that many people had used the Internet to obtain the forbidden information, and that they had distributed it to many more people. “Despite the publication ban [on information on the trial of Karla Homolka], various Internet newsgroups posted details of the case… the information was freely circulated in the U.S. and found its way back north of the border electronically.” (Johnstone, Johnstone and Handa, 1995, 151) Having information about the trial was not, in itself, a crime (only publishing such information was). However, people who got details of the crime over the Internet flouted the intent of the Court’s ruling, which was to ensure that enough people did not know such details so that an unbiased jury could be impaneled for Bernardo’s trial. Because it was so easily circumvented, the ruling came in for much scorn (as do traffic rules which are difficult to enforce), and brought the entire justice system up for ridicule.

Even if a legislative body passes laws to control content on the Internet which hold up in its country, it would still be faced with the problem of jurisdiction. The Internet is a communications system which spans the globe; since information flows more or less freely across borders, laws passed by individual nation-states can be easily circumvented. Worse, since laws passed in one country have no force in other countries, even if a national government can control what its citizens put on the Internet, it cannot control what the citizens of other nations put there.

One way in which computer networks may undermine governments is in the way it allows individuals to act in defiance of laws, making them difficult to enforce. The Homolka trial experience is one example of this.

Soon after the trial of Karla Homolka, a newsgroup was set up on the Internet which contained information on it, alt.fan.karla-homolka. “This newsgroup was started as something of a joke on June 14, 1993, by a University of Waterloo student called Justin Wells who, upon seeing a photograph of Mr. Bernardo’s estranged wife, decided ‘she’s a babe’ and that she needed a fan club. Soon, however, as the horror of the charges against the two became clear, the newsgroup took on a different tone.” (Kapica, 1995, A13) The newsgroup soon came to include “not only discussion of the case but also evidence presented at the trial in which Ms. Homolka was convicted of two counts of manslaughter in the sex slayings…” (Gooderham, 1993, A5) Soon after the trial, it was reported that, “96 different articles have been posted on the Homolka newsgroup, including discussion of the Canadian and U.S. judicial systems, sordid rumours about the case and the text of an article published last week in The Washington Post.” (ibid)

In order to comply with Judge Kovacs’ ban, some Internet Service Providers and universities blocked access to alt.fan.karla-homolka. This was sometimes regarded as an unwelcome attack on free speech. When, on legal advice, Mark Windrim, owner/operator of the MAGIC Bulletin Board Service banned discussion of the Homolka and Bernardo trials online, he earned “a flood of hate E-mail” from subscribers. (Clark, 1994, B28) When the University of Toronto blocked access to newsgroups with information on the trial, the student newspaper The Varsity published a step-by-step guide on how to circumvent the block. According to then-Varsity editor Simona Chiose, “We just wanted to show that despite the university’s effort to censor the information, it can still be obtained.” (Memon, 1994, A8)

For a number of reasons, attempts to block information on the Homolka trial were largely unsuccessful in stopping the banned information from circulating. Writing about the ban at the University of Toronto, for instance, Mary Gooderham pointed out that “the university brings in more than 4,200 other newsgroups, and some of those include the same information as the Homolka one. A newsgroup called alt.journalism, for instance, includes the Washington Post article.” (1993, A5) She went on to state that commercial services made the information available: “CompuServe, one of the largest private on-line computer services, offers the Washington Post article to its subscribers…” (ibid) Furthermore, even if access to the newsgroup at one server was blocked, “any Netsurfer with a little wit could find a ‘mirror site’ — a computer carrying the same newsgroup — in the United States, where the publication ban is not in effect.” (Kapica, 1995, A13) Simply renaming the newsgroup would have gotten around those who were attempting to contain the information; in addition, “users who have had it blocked also have the option of receiving all of the information by electronic mail.” (Gooderham, 1993: A5)

The result of these and other methods around the ban was, according to the Ottawa Citizen, that “26 per cent of those polled knew prohibited details of the Teale [Bernardo]-Homolka trial…” (Wood, 1994)

Coverage of the Homolka trial points out the difference between the Internet and traditional print media as disseminators of information. “A story on the case published this week in Newsweek magazine, titled ‘The Barbie-Ken Murders,’ which was not included in Canadian copies of Newsweek, appeared Sunday on the New York Times Special Features wire service.” (Gooderham, 1993, A5) Although the publishers of Newsweek voluntarily complied with the ban in their print publication, they could not control who could read their article when it was digitized. An even starker example of the difference occurred with a publication which, given that it considers itself part of the vanguard of the digital revolution, should have known to be more careful: “…a single sentence in ‘Paul and Karla Hit the Net’ — a 500-word article on Canadians tapping Internet for banned detail on the Karla Homolka trial — triggered removal of 20,000 Wired mags from retail racks nationwide…distributors in Victoria and across the country scurried to slap stickers over the offending passage in each copy before returning the periodical to the shelves.” (Wood, 1994)

Governments used to be able to control information in traditional print media because, in the worst case, they could seize physical copies of the information, punishing those who were distributing it. Because digital information has no physical form, it is much more difficult to contain, making rules about who can access it much harder to enforce. Although some governments may attempt to control digital information by controlling the physical infrastructure (ie: intervening at the level of service providers), the example of the ban on information on the Homolka trial suggests that this may not be as simple as it has been for previous media (for instance, television).

Another example of a national government being forced to come to terms with new media took place in Serbia, when the Milosevic government attempted to outlaw information which opposed its public line on dissident groups. According to one report, Milosevic was largely successful in controlling traditional media:

In cities now controlled by the opposition, more than 50 TV and radio stations have been closed by the Serbian police on the grounds that their licences were not in order, eliminating alternatives to the heavily controlled propaganda machine of state TV.

And the weekly magazine Nin, considered the most reliable and most serious publication in Serbia, has a new editor-in-chief, Milivoj Glisic, and now embraces a more Serbian, nationalistic editorial policy. A third of the journalists have left in protest. (Perlez, 1997, A9)

According to Dusko Tomasevic, the Milosevic government was not able to shut down news of the regime which made its way onto World Wide Web sites on the Net: “‘The police told students to shut it down, but they cannot,’ Tomasevic says, subdued, matter-of-fact. ‘We have mirror sites now in Europe and North America, and if they shut down the Belgrade server we can directly modem the information overseas. To stop that they will need to shut down every telephone in Serbia — which is impossible.'” (Bennahum, 1997, 168) As Tomasevic claims, anybody with access to the technology can transmit forbidden information from their computer directly to a computer outside their country (and, presumably, outside the control of the government of their nation). Moreover, once the information has been transmitted, it is rapidly disseminated to computers in various nations throughout the world, rendering subsequent control of the source moot.

One of the few remaining independent voices in the region, the radio station B92, had its signal repeatedly jammed before being completely shut down by the Milosevic regime. (Reuters, 1997, A11) In the past, this may have permanently silenced the radio station, but, as it happened, this was not the case:

On December 3 [1995], the Net briefly captured center stage in Belgrade when the Milosevic regime took Radio B92 off the air. B92, then Belgrade’s only radio station that wasn’t under state control, had for two weeks been broadcasting updates on the growing protests in the streets. When Milosevic unplugged B92, the broadcasts were rerouted via the Net using RealAudio. The Voice of America and the BBC also picked up the dispatches, resending them to Serbia via shortwave. Two days later, Milosevic allowed B92 to broadcast again, giving the opposition an important symbolic victory, and inspiring students to start calling their struggle ‘the Internet Revolution.’ (Bennahum, 1997, 168)

Because of their centralized nature, it was once possible for a government to physically seize television or radio transmitters which were used to disseminate information of which the government did not approve. The Internet, being both decentralized and having innumerable points of entry (not only telephone lines, but cable, satellite and, perhaps in time, even power lines), is far more difficult to police in this way. As we saw with print, methods of controlling the medium of radio which once worked are made highly problematic by new digital media.

Some countries are trying. China, for instance,

is in the midst of developing a large academic computing network to link more than one thousand educational institutions by the end of the century. There is only one twist to this network. Unlike American networks, with multiple electronic routes from campus to campus, all traffic in this Chinese network will have to run through Beijing’s Quinghua University. Poon Kee Ho thinks he knows why. The Chinese academic network will be technically unsound, but with a choke point at Quinghua University, government officials ‘can do what they want to monitor it or shut it down’… (Wresch, 1996, 147)

China seems, in fact, to want to return computer networks to the hub-and-spokes model of telephone connectivity in order to be able to exert control over it. Politically, there can be no doubt that the Chinese government has the will to carry this out: as the Tiananmen Square massacre indicates, it is more than willing to defy international opinion to achieve internal political ends. Moreover, the example of Singapore, which has extensive international economic ties despite having repressive laws on Internet use, suggests that governments can attempt to control information flow through computer networks with few repercussions to international relations. (Gibson, 1993)

That having been said, it must be pointed out that the technology works against such centralized control. For one thing, the volume of information passed through China’s system is likely to be huge, with perhaps millions of messages a day. The computing power necessary to monitor such output is mind-boggling. Moreover, how to sift legitimate from illegitimate forms of communications is a logistical nightmare. Simple programmes can be written which will look for certain words (ie: “democracy”) and let the people running the system know in which messages such words occur; but a huge bureaucracy would have to be created to sort through the flagged material to determine what was innocent communications and what was politically unacceptable.

Even if such a system could be set up, Ho’s fear that the Chinese government will shut down the country’s connection to the Internet is probably misplaced. China is currently attempting to increase its educational and corporate connections with the outside world as part of a larger process of helping it to function within the modern world economy. To the extent that the technology is an important part of this process, shutting China’s Internet connection completely would seriously damage these efforts. In this way, unwanted information is somewhat protected by the nation’s need for certain kinds of information; or, as William Wresch eloquently puts it: “Links to the world are innocent. The highway doesn’t know if it is carrying salvation or slaughter.” (1996, 158) As information transfers become increasingly global, as well as increasingly important for international business, the possibility of shutting down local information networks for political reasons becomes increasingly remote.

Even where laws are difficult to enforce, some argue that they still have value. Taylor refers to symbolic legislation, whose purpose is “more ideological than instrumental.” (in press) One major characteristic of symbolic legislation is that “it should espouse a particular social message irrespective of the law’s likely ability to enforce that message.” (ibid) In this way, it can be argued that the ban on information on the Homolka trial, to take one example, should have stayed on the books even after it became clear that it was difficult to enforce in order for the government to be seen to be upholding the ideal of fair trials for the accused. (Ideological purposes need not be benign, however; the Milosevic government of Serbia may outlaw some forms of communication in order to seem to be maintaining control over information in its country even if there are holes in such a ban.)

The danger of symbolic legislation is that it can bring a government into disrepute by making its power to rule a subject of ridicule. This happened in Quebec when local computer company Micro-Bytes Logiciels ran afoul of the Office de la Langue Francais, the government agency charged with protecting the French language in the province, resulting in the company removing most of its home page from the World Wide Web. (“Language Rules,” Montreal Gazette, 1997) According to the OLF, the company’s English-only Web site was a violation of Section 52 of Quebec’s French Language Charter, which reads: “Catalogues, brochures, fliers, commercial directories and all other publications of the same type must be produced in French.” (Beaudoin, 1997, B5)

Reaction to the move was largely negative, the following excerpt from a column in a Montreal alternative weekly being typical: “Where the rest of the world sees a multimedia free-for-all that transcends language, nationality and border, those, um, marvelously iconoclastic individuals at the OLF see printed brochures and neon signs over shoe stores. In NDG. It’s all print advertising to them, and as far as they’re concerned the people who put those print ads on a network that spans the entire globe only intended them to be read by Quebecers.” (Scowen, 1997, 6) The issue was even brought before the federal government when Liberal Member of Parliament Clifford Lincoln scoffed, “The Internet doesn’t belong to Quebec. This isn’t a television channel or a radio station. It’s a totally different entity…” (Contenta, 1997, A2) Beaudoin is not unaware of this: “It has been argued that Quebec cannot exercise jurisdiction over companies located outside its borders that put advertising on the Internet. This is true. But this is no reason, in our view, to abdicate our responsibility to protect Quebec consumers to the extent that we are able.” (1997, B5) This is a clear statement of the symbolic nature of the law. [4]

Two qualifications must be made here. The first is that the French language press seemed more favourably disposed to the ruling on Micro-Bytes Logiciels than the English language press, likely because they have more sympathy for the government’s goal of protecting the French language. The other is that the French language laws are frequently a source of ridicule in Montreal’s English language press. This underscores the point, though, that the more a government’s laws are ridiculed, the greater its legitimacy tends to be undermined. It should also be pointed out that jurisdictional disputes are not limited to nation-states; smaller, more localized governments may also attempt to pass laws which affect the flow of information over digital networks despite how difficult they may be to enforce.

Examples of Internet related challenges to the authority of governments are multiplying. An American company wanting to sell home pregnancy kits over the Internet faces a problem because they cannot legally be sold in Canada. (“E-Commerce Problems,” Ottawa Citizen, 1998) In December, 1996, two organizations dedicated to protecting the French language in Europe sued the Georgia Institute of Technology’s branch in Lorraine because its Web site contained only English (they recently settled out of court). (“English-only Approved for Georgia Tech Web Site in France,” 1998) “During the 1991 attempted coup in Russia…programmers used their computers to keep in touch with the rest of the world, even though the insurgents controlled the centralized radio, television, and newspaper facilities. Messages traveled from Moscow to Vladivostock, to Berkeley, to London, and back, while the technologically illiterate old-timers were powerless to stop them. In the old days, it was easy for Moscow to prescribe what the entire country thought simply by controlling the central broadcasting stations. Not anymore.” (Rawlins, 1996, 80)

As a result of these, and other events, scenarios illustrating the uncontrollable nature of electronic communications networks such as the Internet abound. Nicholas Negroponte, to cite one example, wrote,

If my server is in the British West Indies, are those the laws that apply to, say, my banking? The EU has implied that the answer is yes, while the US remains silent on this matter. What happens if I log in from San Antonio, sell some of my bits to a person in France, and accept digital cash from Germany, which I deposit in Japan? Today, the government of Texas believes I should be paying state taxes, as the transaction would take place (at the start) over wires crossing its jurisdiction. Yikes. As we see, the mind-set of taxes is rooted in concepts like atoms and place. With both of those more or less missing, the basics of taxation will have to change. (1998, 210)

This particular scenario may be overstated. As economist Paul Krugman points out, the movement of people is far from free, and as long as people are physically rooted to one area in one country, it remains possible to make them submit to paying taxes. (Kevin Kelly, 1998, 146)

There are other scenarios which point out the difficulty of local attempts to regulate an international communications system: “Questions that once had clearcut answers are now blurring into meaninglessness. Who should be involved in a computer chase? Who has jurisdiction? If you invade someone’s computer, is that burglary or trespass? Where should the search warrant be issued? And what for? What happens if someone living in country A commits a crime in countries B and C using computers in countries D, E, and F?” (Rawlins, 1996, 83) Or again: “To censor Internet filth at its origins, we would have to enlist the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who could start by invading Sweden and Holland.” (Noam, 1998, 19)

One obvious solution to this problem is for national governments to enter into agreements with each other to regulate international digital communications networks. The likelihood of the nations of the world, with their wildly disparate cultures, agreeing on policies for policing Internet content seems remote; even if it were possible, methods of circumventing such policies makes their enforceability by no means certain. Finally, there will be a hidden cost to such efforts. “In order to combat communicative acts that are defined by one state as illegal, nations are being compelled to coordinate their laws, putting their vaunted ‘sovereignty’ in question.” (Poster, 1995, unpaginated) Ironically, attempts to protect national sovereignty by controlling Internet content may, in this way, lead to it being undermined.

Another problem with any sort of regulation of Internet content is, according to many observers, that the freedom to publish on the Internet is what makes it such a dynamic source of information. “To impose local norms on media that are inherently unlocal is to cripple the media themselves… With enough sufficiently different local norms brought into play, the network will be permitted to transmit nothing but mush.” (Noam, 1998, 46) The irony here is that efforts to “save” the Internet (from, say, purveyors of pornography) may reduce it to something not worth saving.

Some commentators suggest that computer networks will make nation states obsolete. Don Tapscott, for instance, writes: “There is evidence that the I-Way will result in geopolitical disintermediation, undermining the role of everything in the middle, including the nation-state. That is, broadband networks may accelerate polarization of activity toward both the global and the local…” (1996, 310) I am not suggesting this. As I argued previously, governments are instruments of the collective will of citizens and, as such, will continue to serve a legitimate purpose for the foreseeable future. In particular, we should expect them to continue to attempt to regulate communications media, including the Internet. However, any government attempt to regulate digital communication networks, as they are currently configured, must take into account the way the technology can constrain the ways in which governments can act.

As we have seen, many of the writers surveyed in Chapter Two are concerned about whether or not traditional notions of copyright will apply to digital communications media. Some are worried that if they cannot exert copyright protections for their writing, they will not be able to make money from it once mechanisms for revenue generation are perfected. Others are concerned that, given the ease with which digital works can be copied and modified, they will not be able to control where or how their work appears without strong copyright protections.

On the other hand, those pushing for stringent application of copyright to digital media the loudest are the transnational entertainment corporations that hope to reap vast profits from the Internet. The tension between these two interests, as well as other issues arising out of the application of traditional notions of copyright to the emerging medium of digital communication networks, is the subject of this section.

A Note About Terms: Are Expressions Property?

Before beginning a discussion of copyright, it is worth noting that a central term used in most such discussions is “intellectual property.” This term is largely a metaphor, comparing the right somebody has in intellectual expression to the right they may have in owning a car, a house, or any other physical commodity. I find the term misleading, leading to extensions of concepts from the physical world to the purely ideational world regardless of whether or not they actually fit well with our experience of the ideational world.

The obvious difference between the two is their tangibility: property rights have traditionally been exerted over physical objects. Expressions of ideas, by way of contrast, may be embodied in a physical object (a book, say, or a videotape), but their essence is not physical; this is made clear by digital media, where messages are transported over vast physical networks, but, themselves, take the form of impulses of light.

The most important aspect of the rights inherent in owning physical property is that its owner has absolute control over what is done with it. Thus, the owner of a car determines who can drive it; the owner of a house determines who can live in it and what activities are permissible within its boundaries, and so on. This is necessary because there is only the one object; if a dispute arises in which it becomes necessary to determine who has the right to decide what will be done with the object, the concept of who “owns” it, whose property it is, is invoked.

When it comes to the expression of ideas, we have seen (and will have cause to consider again) that this is not the case. When somebody buys information, the person who created it can retain a copy. Moreover, information proliferates: whether emailed to a thousand people on a list or talked about around an office cooler, information is soon distributed beyond the ability of its creator to control. Last chapter, we saw some proposed technical solutions to this problem in the digital world; in this chapter, we will look at a legal solution. It is unclear whether any of these solutions will work (indeed, some people believe they will be fruitless and might as well be abandoned); in fact, as we shall shortly see, extending such power too far may be to the detriment of society as a whole. I would suggest part of the reason control of ideas and the expression of ideas is so difficult is that the metaphor of property which is the basis of such attempts at control does not apply to information.

For this reason, although many of the thinkers I quote in this section use the term “intellectual property,” I do not.

What Is Copyright?

If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of everyone, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it…. He who receives an idea from me, receives instructions himself without lessening mine as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me. That ideas should be spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature… (Thomas Jefferson, quoted in Samuelson, 1998, unpaginated)

Our commonsense understanding of the way literature works suggests that authors should be rewarded for their work. In fact, it took a long time for such an understanding to be developed, and, even now, long after regulatory regimes were developed in order to protect the interests of authors, their aims and effects are poorly understood.

As described in Chapter One, in the 16th Century Gutenberg’s press spread throughout Europe; the books which were printed on it tended to be ancient texts, largely the Bible, but also many of the philosophical works of the Greeks. Because they were long dead, compensation for the authors of these works was not seen to be important. However, the publishers of these works had a serious economic stake in them: it was not uncommon for a publisher to go to the trouble and expense of developing a volume, only to see it exactly reproduced at lower cost by another publisher. A group of publishers banded together and successfully lobbied the British government for protection, which it granted them; in 1557, the Stationer’s Company, as this group was called, was given exclusive control over all printing and book selling in England. (Gutstein, 1999, 129)

As publishing grew, individual authors were encouraged to write new works. However, because the Stationer’s Company had a monopoly on publishing, it was able to dictate the terms under which British authors would be compensated for their efforts. Most often, the author was given a lump sum payment for a work, and had no legal recourse to any other payment, even if the book went on to become a bestseller which made a lot of money for the publisher. Note this economic imbalance, which favoured the interests of publishers over authors and was supported by statute: it will appear again in modern times.

The Stationer’s monopoly on publishing lasted for 150 years, until the passage of the Statute of Anne in 1709. (ibid, 130) The rights enshrined in this Statute were to be reproduced in the American Constitution some 80 or so years later. According to this latter document, copyright is intended to “promote the progress of science and the useful arts,” by giving the creator of a work, for a limited period of time, the right to control the dissemination of, and thereby profit from, that work. Several things are noteworthy about this formulation of copyright. The most obvious is that publishers are not mentioned; the most important economic stake in an original work is now identified as the author’s. (In fact, an exception has arisen: “…generally the copyright in a work is owned by the individual who creates the work, except for full-time employees working within the scope of their employment and copyrights which are assigned in writing.” (Brinson and Radcliffe, 1991, unpaginated) However, in the cases in which we are most interested, particularly individuals who put their work on a Web page, this exception does not apply.)

Perhaps more important to note about this way of looking at copyright is the idea that it is granted to artists and other creators by society for society’s benefit. “Copyright — the right of a creator to impose a monopoly on the distribution of his or her work — was originally conceived [in Canada] as a privilege bestowed by Parliament on authors to encourage the creation of new ideas, which society needed to continue its development.” (Gutstein, 1999, 3) This privilege is, in fact, severely circumscribed. For example, “Under copyright law, only an author’s particular expression of an idea, and not the idea itself, is protectible.” (Jassin, 1998, 6) For example, you cannot copyright the idea that the sun is shining in the sky, because this would make it illegal for any other author to write anything on this very common observation. However, if you are Samuel Beckett, you can copyright the unique expression which opens the novel Murphy: “The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new.” (1976, 24)